Photographs by Robert F. Bukaty After being warmly welcomed by dockhands at the Dolphin Marina in Harpswell, Maine, Herb and Ruth Weiss laugh after Herb shared one of his corny jokes. The couple sailed worldwide and bought a trawler when Herb was 95.

After being warmly welcomed by dockhands at the Dolphin Marina in Harpswell, Maine, Herb and Ruth Weiss laugh after Herb shared one of his corny jokes. The couple sailed worldwide and bought a trawler when Herb was 95.

On a perfect early summer morning with barely a ripple in the water and a bluebird sky overhead, Herb Weiss deftly backed the 36-foot trawler Ancient Mariners dockside at the Dolphin Marina in Harpswell, Maine.

An hour-and-a half earlier, the American Tug had left DiMillo’s Marina in Portland, skirting between islands in Casco Bay. Herb was at the helm and his wife, Ruth, stood next to him monitoring the course with an iPad.

That’s not such a big deal for most boaters. But Herb will be 104 on October 4; Ruth is 96. They not only boat alone, they bought an even bigger boat over the summer.

Ruth, barefoot and tanned, tossed lines to dockhands who eagerly waited at the Dolphin marina pier to welcome the couple. The Weisses, both grinning, were excited to be back at one of their favorite summer spots. After years of cruising along the coast of Maine, they’re celebrities. “We get to see old friends everywhere,” said Ruth. “Actually, that’s a significant part of cruising for me.”

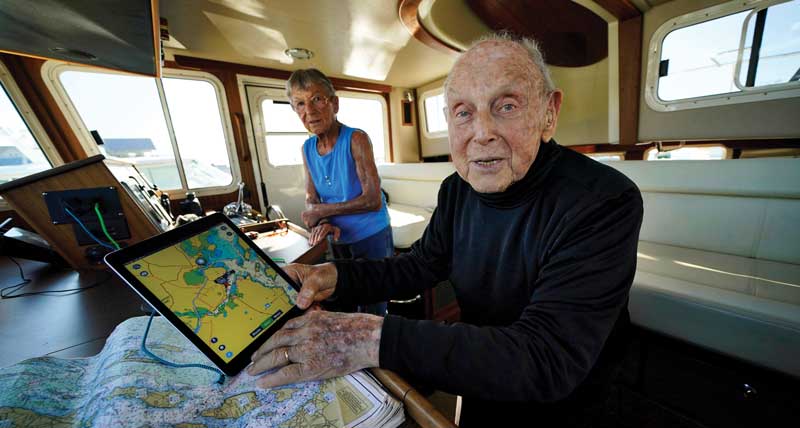

The Weisses plot their course on an iPad, backed up by paper charts.

The Weisses plot their course on an iPad, backed up by paper charts.

A photographer snapped photos as the couple unscrewed turnbuckles and lowered the dinghy from the stern. “Everywhere we go they bow down to us,” teased Herb, a master of jokes and one-liners.

“Did you hear about the woman who walked down a ramp at low tide and complained about how steep it was?” he quipped to onlookers. “She walked back up at high tide and said, ‘I’m so glad you fixed it!’”

The dockhands chuckled or groaned. “I’ll be back in the morning with blueberry muffins and coffee,” shouted marina hand Tyler Nadeau as he and other crew members headed back to work. For the Weisses, it was time for lunch and a nap.

How does a couple, whose combined age is 200 years, keep on boating?

“We plan everything carefully and we just do it,” said Ruth. In earlier years, they hiked and climbed mountains. “You’re huffing and puffing the last few yards. It’s the same thing with boating.

“We never stayed at docks when we were younger,” she continued. “We’d pick up a mooring or drop the hook. We were being frugal, maybe too frugal. We started going to docks when we bought the powerboat. That’s when Herb was 95.”

After cruising thousands of miles, the Weisses gave up sailing and bought a 36-foot American Tug. Undaunted by their ages, they planned to sell Ancient Mariners this summer to buy an even bigger boat—a 41-foot tug, Ancient Mariners II.

After cruising thousands of miles, the Weisses gave up sailing and bought a 36-foot American Tug. Undaunted by their ages, they planned to sell Ancient Mariners this summer to buy an even bigger boat—a 41-foot tug, Ancient Mariners II.

Their favorite places to cruise these days are Portland and Harpswell in Casco Bay, and Rockland, Camden, and Belfast in Penobscot Bay. “Marinas put us near the ramp so Herb doesn’t have to walk on shaky docks that wobble,” Ruth said. “If we need an emergency medical technician, it’s faster if you’re on the mainland. We haven’t needed one and it was a concession to our kids who were worried about us.”

It doesn’t matter how many birthdays pile up, cruising is in their blood. The Weisses started seriously boating in the 1970s when they bought a one-quarter interest in a 37-foot wooden Chesapeake Bay, Ericson look-alike racing boat that “leaked top and bottom.” They eventually bought out their partners, but after a year’s worth of upkeep sold it, and purchased Talaria, a Tartan 37. Then came Windpower, a 42-foot Hallberg-Rassy ketch, followed by the first Ancient Mariners.

Ancient Mariners and its dinghy, Rime, are a nod to English poet Samuel Coleridge’s poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Friends planned to deliver the newest boat—a 2006, 41-foot American Tug—from Virginia to Maine over the summer of 2022. The Weisses intended to christen it Ancient Mariners II, for “two old boaters.”

Over the last half-century, they’ve sailed or motored at least 40,000 miles in Western European waters and the Mediterranean as far as Turkey, Lebanon, Cyprus, and Israel. (Turkey was their favorite.) They’ve crossed the Atlantic and dropped anchor or pulled into ports in the Canadian Maritimes, New England, the Intracoastal Waterway, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean, and as far as Central and South America.

Herb got bitten by the sailing bug after enrolling at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1936. “The most important thing I did (at MIT) was learn to sail,” he said, with a smile. He earned a degree in electrical engineering in 1940 and eventually gained a resume as long as his arm, the envy of anyone in the field of radar and national defense systems. Ruth graduated from Harvard Medical School in 1951.

The couple’s minds remain razor sharp. On most days at 5 p.m., Ruth and Herb fill glasses with wine from a box. He is short and bald and there’s always a smile on his moon-shaped face and a twinkle in his eye. When he wants to tune out the world, he said he takes out his hearing aids. She is short, slender, and limber, with short-cropped hair, tortoise-rimmed glasses, and hearing aids. She could pass for decades younger. When not in the galley or bridge, you might find her on her knees cleaning the boat.

Ruth makes it clear Herb is the more accomplished sailor. “I am good at many things,” she said, “planning, organizing, cooking, medical care, navigating—including celestial. The most technical thing I ever did was get my ham radio license. The only boat I have ever taken out alone is a dinghy.”

For long trips on the ocean, often with no other boats around, another level of competence is needed, she continued. “Changes in weather and sea conditions and sudden malfunction of a well-cared for boat require someone who can quickly think things through and come up with a solution. On a boat there’s always a time when there’s a crisis. I shriek. Herb smiles and says, ‘It’s a challenge.’ We can be in the middle of the Atlantic with all hell breaking loose and Herb is in there fixing everything.”

Ruth and Herb Weiss compare their summer cruising itinerary, Ruth on her phone and Herb on his laptop, before leaving DiMillo’s Marina in mid-June.

Ruth and Herb Weiss compare their summer cruising itinerary, Ruth on her phone and Herb on his laptop, before leaving DiMillo’s Marina in mid-June.

Growing up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Herb liked gadgetry. As a teenager, he became a ham radio operator and built a primitive television set at the same time NBC was trying to get its first signal on the air. His shop teacher was so impressed by Herb’s genius that he contacted MIT, which invited Herb to attend the college.

He spent the bulk of his career developing radar when there was none in the United States. He joined the Radiation Lab at MIT, which was just being established to support the war effort during World War II, designing radars for ships and aircraft. In 1942, when England was in the throes of its air war with the Nazis, Herb went to England and installed radar in planes with a novel navigation system that he and a team had designed for the Royal Air Force. He later spent three years at the Los Alamos, New Mexico, laboratory improving instruments for the A-bomb. After seeing the need for a continental defense network against the Soviet missile threat, he returned to MIT to build it. If not for Herb, there also likely would be no MIT Haystack Observatory, a pioneering radio science and research facility.

Ruth, whose family lived in Newton, Massachusetts, had completed two-and-a-half years at Radcliffe when she learned that medical schools were accepting women. She applied to Harvard, Tufts, and Boston University. Tufts and BU wouldn’t accept her because she wasn’t a college graduate. Harvard did. But after two years, she was forced to leave school because her parents didn’t have the $800 for the third year. “You might as well call it quits,” her father told her, “because you’re only going to get married anyway.”

She met Herb in 1949 at a party in Cambridge. He asked Ruth to marry him on their first date and three weeks later they wed in her parents’ living room. There were 13 guests. Her mother had rented palm trees for each side of the fireplace. A music box played “Here Comes the Bride.”

Herb went back to work at MIT developing radar systems, and gave his bride the $800 she needed to finish medical school. After graduating, Ruth eventually opened her own practice, retiring in 1982. The couple, who have been married for 73 years, lived in Lexington, Massachusetts. Their three sons all graduated from Harvard. Walter, 72, is a retired physician; Fred, 70, is an investment advisor; and John, 67, owns independent newspapers in Colorado.

When John was a toddler, the Weisses chartered a 30-foot wooden sloop and sailed from Boston to Nantucket. In 1972, they bought Talaria for weekend cruising. “Since Talaria was very tender, when the wind was 12 knots, we reefed the main. We dropped our own mooring in Marion (Massachusetts) and for the first time ventured to Maine,” said Ruth. Six years later, they took Talaria to the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and the Caribbean.

In 1982, just shy of Herb’s 65th birthday, they flew to Sweden and bought Windpower. “For the next five years we were full-time cruisers in Western Europe and the Caribbean,” she said. “In those days the cruising community was small and friendly. Marinas were few, except in France. Cruising guides, especially in English, were almost nonexistent. We would see a breakwater, assume it was a harbor, tie up at the town dock with the locals and become part of the community for as long as we liked.”

Ruth Weiss is all smiles as Herb Weiss maneuvers Ancient Mariners toward the dock at the Dolphin Marina in Harpswell, Maine, their first stop this summer.

Ruth Weiss is all smiles as Herb Weiss maneuvers Ancient Mariners toward the dock at the Dolphin Marina in Harpswell, Maine, their first stop this summer.

One of their few harrowing boating experiences was in the spring of 1978. Ruth was at the helm of Talaria heading to the Bahamas from the Turks and Caicos in a 20-knot easterly. “I tacked and the fitting broke at the top of the mast. The sails and rigging were in the water,” Ruth recalled. “I did the wrong thing and started the engine and the lines got tangled in the propeller.” Herb dropped three anchors, because they were a few hundred yards upwind of a rocky coast with 10-foot seas. With no sails or functioning engine power, Herb put out a May Day distress call. Using the ham radio, he eventually was able to reach an amateur ham radio operator in Montana who contacted the Miami Coast Guard. The Coast Guard responded via patched radio messages that the closest available help was in Florida or Puerto Rico, hundreds of miles away. In ham radio relays back to the Coast Guard, Herb said a fellow sailor they had met several weeks earlier in the Turks and Caicos was a scuba diver and had a plane, and if the Coast Guard could track him down, he might be able to dive off Talaria to untangle the lines. “He clearly was a drug lord,” added Ruth.

The Coast Guard found the man that night in a bar. He flew out the next day and landed on a dirt road on nearby Acklins Island where he found a minister with a small boat who took him out to Talaria. But the man couldn’t dive under the boat because the seas were too rough. “Your only choice is to jump into the water and we’ll pick you up, but then your boat is gone,” he said. Ruth replied that they could not leave the boat because it wasn’t insured. Herb then took a new approach, running the engine, lines still wrapped around the prop, forward and back. The tactic worked, and they followed the pilot and preacher to a safe cove where, “we opened a bottle of scotch,” said Ruth.

When Herb was 85, he and Ruth began sailing only in the summers. A decade later they bought the first Ancient Mariners. “Cruising on a powerboat isn’t too thrilling,” said Ruth, “but the many friends we’ve made along the way still make it a wonderful life.” The trawler “doesn’t have the exhilaration of a sailboat,” added Herb. “It’s sort of like living on a houseboat.”

In late autumn, the Weisses planned to head back south to DiMillo’s Marina in Portland for a few days before having the new boat, Ancient Mariners II, hauled at the nearby Maine Yacht Center. They intended to return to Florida on a private jet—safer when Covid cases still abound—to spend the winter at their Boca Raton condo. They’ve been blessed with good health—Herb has a pacemaker and Ruth recently had cornea transplants—and will continue boating as long as they can. “I’m 103 and Ruth is 96,” said Herb. “You add the two together and that’s a pretty old crew.”

Connie Sage Conner is a retired editor at The Virginian-Pilot. She and her husband cruised on their Kadey-Krogen, Epilogue, with their two cats. They live in Harpswell, Maine.