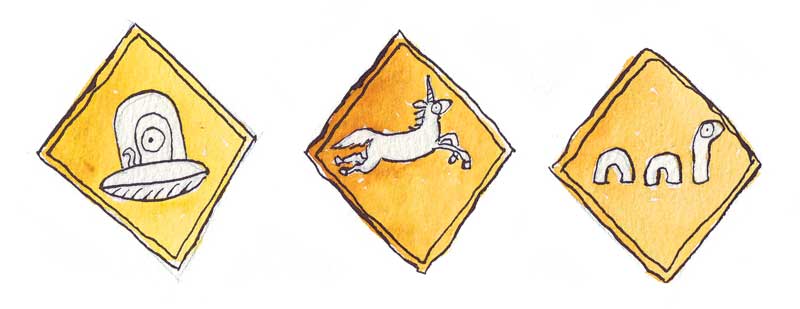

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

“Ron, the blinking line is for you,” said Rosalie, my secretary at the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife office in Greenville. “The caller is an animated woman,” she added with a wink and a smirk. “And boy does she have a whopper of a story.”

Rosalie took great pleasure eavesdropping on zany calls. I braced myself, picked up the receiver and said, “Hello, this is Ron Joseph, state regional wildlife biologist in the Moosehead Lake Region. How can I help you?”

“My name is Louise,” she answered, “I live in Guilford. This morning while walking to my mailbox, I watched a white unicorn race across the driveway in front of me. I thought I saw the animal a few weeks ago but wasn’t sure. Today, though, I had great views of it. They’re much larger than I imagined. Are they endangered?”

I listened impassively to her wildlife observation, concluding that it wasn’t a prank call. She had either misidentified the animal or was hallucinating. I gave her my mailing address and suggested she carry a camera on walks to the mailbox. Louise eagerly agreed to send me a photograph of the unicorn. I never heard from her again.

Dozens of humorous and odd public wildlife observations are shared annually with Maine biologists and game wardens. Here are three of my favorites.

Deer Crossing Sign

In the late 1980s, after a June day counting eider nests on Matinicus Rock, fellow biologist Gene Dumont and I returned to his Augusta office. A woman in Belgrade had left him an urgent message to call her back immediately. Gene dialed her number. Sitting nearby, I overheard bits of his side of the conversation. Professional wildlife biologists have learned that the public, by and large, is more interested in sharing their wildlife observations than in our feedback. I heard Gene say, “Is that right?” and “uh huh” several times, but not much else. Ten minutes later, he hung up the phone and turned to me with a look of bewilderment. “Do you remember the 400 acres in Belgrade that was deeded to our agency?” he asked. “A few days ago the land donation made front page news in the Waterville newspaper. The caller was a woman from New York City. Last week she arrived at her summer home in Belgrade, which happens to abut our newly acquired property. Since our property will be managed as a wildlife preserve, she asked me if we’d move the deer-crossing sign from her property to ours. I asked why and she replied, ‘I no longer want the deer to cross my property. The animals should now be directed to cross on your property.’”

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Moose on Beau Lake

In 1957, Maine Game Warden Phil Dumond moved to Estcourt Station, Maine’s northernmost outpost. He spent his entire 38-year career there apprehending Quebecois poaching Maine moose and deer. I first met Dumond in 1978. He was raised in a large Franco-American family in Fort Kent, where French was spoken; the language served him well in bilingual Estcourt Station, a tiny town divided by an international boundary line. Several houses on Phil’s street are actually bisected by the line. Some residents literally sleep with their head in Quebec and their feet in Maine. “The boundary is one big messy mistake,” Phil told me once, during a supper we shared in Canada, a few hundred feet from his Maine home. “It was supposed to have been a straight line, but it’s convoluted because the surveying crew—half American and half Canadian—were very drunk the day the border was delineated.”

This is my favorite of Dumond’s many stories he shared with me about his life as a game warden patrolling 1,440 square miles of forestlands crisscrossed by logging roads: “One October day, while walking the boundary, I saw a small, motorized aluminum boat with two people in it zipping across Beau Lake from the Quebec side into Maine. When their boat disappeared around a peninsula, I ran through the woods to try and keep them in sight. Before I saw them, I heard yelling in French followed by the loud sound of metal scraping on rocks. Ten minutes later I watched them frantically row back to Canada. I worked my way along the shore and found green paint on shoreline boulders and parted alder bushes. I couldn’t understand how a boat could crash like that in broad daylight.”

A few months later the mystery was solved at a Christmas party in Estcourt Station. “Two men from Quebec asked me, ‘Are you the game warden who watched us cross Beau Lake last October?’ I nodded yes. And they said, ‘We have a confession to make. A large bull moose was swimming in the water on the Maine side so we lassoed him with the bowline. We’d planned to drag him to the Canadian shore where we’d shoot him. But the moose was very strong and didn’t want to go to Canada. So instead of us pulling him, he pulled our boat over rocks and into the bushes. Once ashore, the moose was tired and angry, and he charged at us with his head down. I got the slack line off his antlers. He caught his breath and trotted into the Maine woods; we paddled back to Quebec with a broken boat motor. Later, we made our confessions to the priest who asked us to confess our sins to you as penance. We are sorry.’”

Transporting a Dead Deer

Deer hunting is an economic lifeline in Greenville, bridging the gap between the summer tourist season and winter’s snowmobiling, skiing, and ice fishing. On Sundays, when hunting is not allowed, many hunters head home. It was my job to briefly detain them at a deer check station a few miles south of town. One Vermont hunter was particularly happy to be interviewed. “Hey Ron, do you remember me?” he asked, as he read the brass name plate pinned to my state wildlife uniform. “You checked the tag on my dead deer last year.” Each November in the late 1980s, I operated a weekend deer check station. “Sorry,” I answered, “I interview about 100 hunters each year.”

“Last November,” he continued, “at this rest area, you examined a nice buck I’d shot northwest of Moosehead Lake. Since the deer was stored inside my Dodge Ram Charger, you warned me that I might be ticketed by a game warden if part of the deer wasn’t displayed outside the vehicle. (This law has since been rescinded.) So, to be legal, I closed the rear door on the deer’s tail. That way if a warden followed me he could see that I was transporting a deer.”

He said he had waited a year to tell me the rest of the story. “I hopped on I-95 south in Newport and hadn’t gone but 20 miles or so when the vehicle behind me flashed its headlights to get my attention. I glanced in the rearview mirror and saw that it wasn’t a law enforcement vehicle, so I kept driving. A few minutes later the vehicle, driven by an elderly woman, pulled up alongside me. She tooted the horn and motioned for me to pull over. This went on for several miles. I finally relented by stopping in the breakdown lane. She parked her vehicle behind mine, walked up to my open window, and said with irritation, “Mister, I’ve been trying to get your attention for the last 10 miles. Your dog’s tail is stuck in the car door!”

Writer Ronald Joseph is a retired Maine wildlife biologist. He lives in central Maine.