All photos courtesy David Wolfe

David Wolfe printing on his Albion iron hand press. The press appeared in the 2019 film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women.

David Wolfe printing on his Albion iron hand press. The press appeared in the 2019 film adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women.

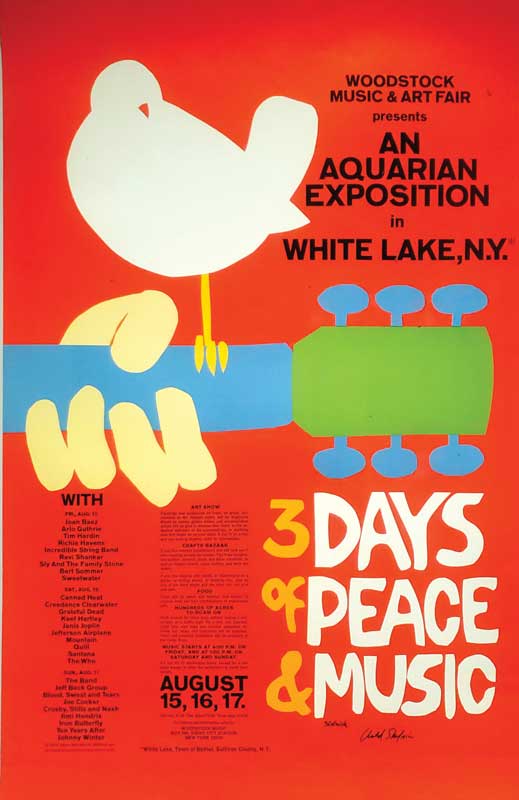

“Printmaking is a collaborative process, it always has been,” said master printer David Wolfe. The walls of his studio in the Bakery Studios building on Pleasant Street in Portland, Maine, testify to the range of that teamwork, from woodcut prints by Charlie Hewitt and Anna Hepler to a silkscreen facsimile of Arnold Skolnick’s original Woodstock poster.

When working with an artist, Wolfe said he must be the master printer they need; some want him to be a technician while others seek more artistic guidance. For example, take painter/sculptor/printmaker Hewitt: “He’s talking to me and getting ideas and I’m talking to him and finding out what he wants,” Wolfe said. He helped design the retro automotive sign typeface for Hewitt’s acclaimed Hopeful neon signs and has provided feedback on many of his prints. As a true measure of their friendship, he recently helped Hewitt paint his new studio in Portland.

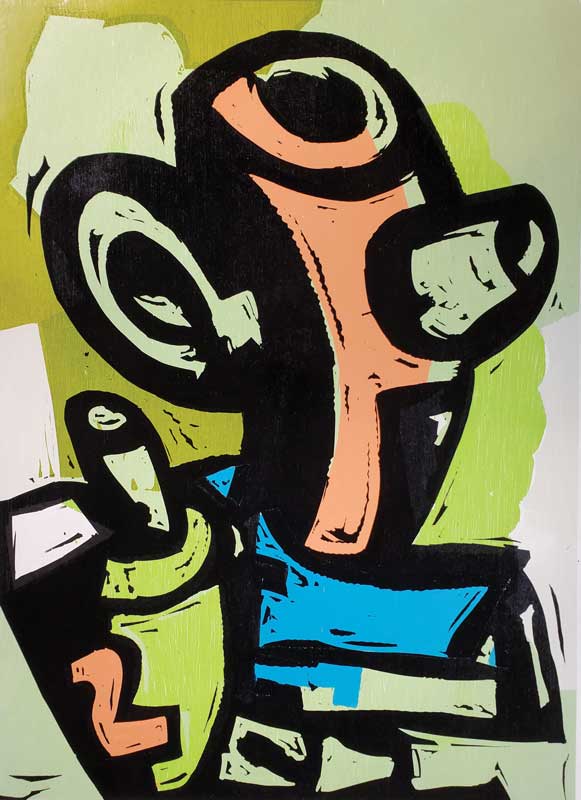

One of the many prints by Charlie Hewitt created at David Wolfe Editions. Charlie Hewitt, Work Bench, woodcut and linocut, 2020, 26" x 22".Each collaboration presents a different scenario. In 2016 Wolfe partnered with Maine art icon Dahlov Ipcar to produce a limited-edition woodblock print to benefit the Student Scholarship Fund at the Maine College of Art. He drove to Georgetown Island to meet with the then 98-year-old artist. Settling on Odalisque, a stunning and complex rendering of a cat, Ipcar asked Wolfe if he would cut it, explaining that her hands could no longer hold onto the gouges.

One of the many prints by Charlie Hewitt created at David Wolfe Editions. Charlie Hewitt, Work Bench, woodcut and linocut, 2020, 26" x 22".Each collaboration presents a different scenario. In 2016 Wolfe partnered with Maine art icon Dahlov Ipcar to produce a limited-edition woodblock print to benefit the Student Scholarship Fund at the Maine College of Art. He drove to Georgetown Island to meet with the then 98-year-old artist. Settling on Odalisque, a stunning and complex rendering of a cat, Ipcar asked Wolfe if he would cut it, explaining that her hands could no longer hold onto the gouges.

Wolfe figured out how he would do the print, carved it, and sent Ipcar proofs. After getting her okay, he took the prints to her home for her to sign. He noted that this arrangement harks back to the more traditional way woodcuts were produced, whereby the artist’s drawings would be sent to a printer who would hire a cutter to carve the woodblock.

Some of his partnerships are long-term. In 2007, the Tides Institute and Museum of Art in Eastport, Maine, commissioned Wolfe to design and produce the first of 23 place-based, limited-edition letterpress printed posters that reflect TIMA’s activities and the eastern coast of Maine, including the annual New Year’s Sardine Drop. Wolfe has worked with Siri Beckman, Petra Simmons, the late David Moses Bridges, and other artists on individual posters.

Suntup Editions in Irvine, California, recently approached Wolfe to print a letterpress book, one of a series of limited-edition classic novels illustrated by contemporary artists. Again, back and forth was involved. During production, Wolfe might call the designer to ask, “What’s your style for ellipses?”—because there are different approaches to how those three dots appear in a text.

Sean Wolfe hand-sewing pages of a book at his shop in Addison.

Sean Wolfe hand-sewing pages of a book at his shop in Addison.

These days, Wolfe’s most significant collaboration involves his son Sean. The two have been working together since 2010 when Wolfe fils left his studies of theoretical physics to join the business. “He’s been around printing presses since he could walk,” explained his father. “That’s a rarity in my field,” Wolfe noted, “to have somebody coming along who truly wants to do the work” despite the challenges.

In 2018, Wolfe helped his son set up a shop in Eastport. Last year, Sean and his family resettled in nearby Addison, where he now maintains Wolfe Press. While the pandemic put a dent in his plans, the press is up and running. “Our goal is to move most of the typographic and bindery work down there [to Addison] and expand the art printing in Portland,” David Wolfe explained.

Over the years Wolfe has accumulated a wide assortment of presses. He was reluctant to name his favorite, but he does love the Tufts Acorn iron hand press, citing its simplicity, control, and beauty. The Civil War-era press made a cameo appearance in the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women. As he told Portland Press Herald arts reporter Bob Keyes, “It’s nice to have a chance to demonstrate [printing] skills accurately and with authenticity on such a scale.”

Wolfe’s portrait of Molly Molasses (1776-1867) is based on an 1860s photograph of the Penobscot medicine woman. Molly Molasses, 2017, two-color woodcut, 96" x 48".Wolfe also owns an Italian cylinder press built in the 1950s. A guy in California said he could have the press if he could come and get it, so he flew out with his son, rented a truck, and drove it home to Portland. “Your average person looking at it wouldn’t find it attractive,” Wolfe said, “but to me it’s like a beautiful Italian espresso maker.”

Wolfe’s portrait of Molly Molasses (1776-1867) is based on an 1860s photograph of the Penobscot medicine woman. Molly Molasses, 2017, two-color woodcut, 96" x 48".Wolfe also owns an Italian cylinder press built in the 1950s. A guy in California said he could have the press if he could come and get it, so he flew out with his son, rented a truck, and drove it home to Portland. “Your average person looking at it wouldn’t find it attractive,” Wolfe said, “but to me it’s like a beautiful Italian espresso maker.”

Wolfe works with hand type, linotype, and monotype. The first-named process dates back to the 1450s, the latter two were invented around 1900. All three methods of producing type were revolutionary in their time, increasing availability to knowledge. For books, he uses the monotype or linotype machines, with titles and other elements sometimes hand-set.

The printing presses are his passion. “If I wasn’t a printer,” Wolfe said, “I’d be a machinist: I just love the physicality of it all.” He noted that the monotype machine is basically as complicated a mechanical tool as existed before the computer took over.

Wolfe supplements his income by leading workshops. He designs them so the students get “almost instant gratification.” He has found that if they get discouraged on their first print, they’ll never do it again. He also offers a master printer program in which he will work for a year or so with an individual who wants to become a fine art or letterpress printer.

In between projects, Wolfe pursues his own creative vision. In addition to handsome broadsides, he has made compelling multi-color woodcuts, including “Cowboys and Indians” portraits. His image of Molly Molasses (1775-1867), a forthright member of the Penobscot Nation, is based on a photograph from the 1860s. “She was discriminated against as all indigenous people are,” Wolfe said. His portrait celebrates her independent spirit.

With its coarse outlines the print recalls the work of one of Wolfe’s heroes, the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), a lithographer who used relief printing to produce popular illustrations for the newspapers. Posada’s work reminds Wolfe of street art, which he loves. “I think printmaking was originally made for people who couldn’t read,” he said, and he embraces that vision of bringing art to the people.

Wolfe worked with Elizabeth Moss at Moss Galleries in Falmouth and Portland to produce this facsimile of Arnold Skolnick’s famous Woodstock poster. Woodstock, 2021, silkscreen, 38" x 26". Born in Baltimore in 1957, Wolfe moved to New Hampshire when he was young. Years later, he returned to his native city to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art. He went there to study photography, but found he couldn’t afford a roll of film every week. Discovering the printmaking department, he embraced this medium because it was cool and affordable: “I could buy an [etching] plate and work on it all semester.”

Wolfe worked with Elizabeth Moss at Moss Galleries in Falmouth and Portland to produce this facsimile of Arnold Skolnick’s famous Woodstock poster. Woodstock, 2021, silkscreen, 38" x 26". Born in Baltimore in 1957, Wolfe moved to New Hampshire when he was young. Years later, he returned to his native city to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art. He went there to study photography, but found he couldn’t afford a roll of film every week. Discovering the printmaking department, he embraced this medium because it was cool and affordable: “I could buy an [etching] plate and work on it all semester.”

In 1979, Wolfe moved to Portland, drawn to its lively art scene, and joined the Anthoensen Press in the Old Port. He started out sweeping floors, but soon moved up through the ranks. The press was the closest thing to fine art printmaking, his first love, and he quickly fell for letterpress printing. He especially admired the books the press produced for the Limited Editions Club in New York City, which incorporated fine art printmaking, be it Alice Neel’s etchings for Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher or Robert Ryman’s color aquatints for Samuel Beckett’s Nohow On.

When the press struggled financially, Wolfe teamed up with the general manager, Harry Milliken (1924-1997), to launch Shagbark Press. When Milliken retired, they sold the business to another master printer, Scott Vile, at the Ascensius Press in Portland.

Around that time, Wolfe got a job offer from Stinehour Press, so he moved to Lunenberg, Vermont, to join one of the foremost letterpress printers in the country. Established in 1950, the press had expanded when Stinehour bought Meriden Gravure, a lithography shop in Connecticut. The company employed about 80 people, four of whom, Wolfe included, ran the letterpress part of the operation. He worked with calligrapher and book and type designer Jerry Kelly, and master printer Freeman Keith.

The company president, Rocky Stinehour, became a mentor. He invited Wolfe to help him teach a summer workshop in printing at Dartmouth College, which he did for 12 years. Stinehour also sent Wolfe to the Rochester Institute of Technology to study iron hand press printing with Gabriel Rummonds.

When Stinehour decided to downsize, Wolfe returned to Portland where he briefly worked for Vile. In the late 1990s he took a leap of faith and started his own business, Wolfe Editions. In the beginning it was a financial balancing act. He sometimes didn’t know where his rent was coming from.

Wolfe eventually settled in the Bakery Studios building, a wonderful warren of artist spaces. His neighbors include Alison Hildreth, Katarina Weslien, Alice Spencer, Peregrine Press, and the Todd Webb Archive.

Asked about his printing heroes, Wolfe offered a diverse list, from letterpress printer and illustrator Wanda Gág (1893-1946) to the woodcut artist Antonio Frasconi (1919-2013). He produced two prints for artist Leonard Baskin (1922-2000), who signed one of them with the comment, “For a nearly perfect print job.” Wolfe also looks back to “the lord of letterpress” Harold McGrath (1921-2000), who “made Baskin’s books shine.”

Artist Anna Hepler has worked with Wolfe on editions of several of her prints, including Untitled, 2008, woodcut, 18" x 22". “You’re influenced by people whose art you like or respect,” said Wolfe. The more important heroes, he asserted, are the ones in his immediate circle: his son Sean; fellow printer Scott Vile; Andrew Steeves at Gaspereau Press in Nova Scotia; and artist Isak Applin from Queens, New York, who has produced prints and books at Wolfe’s studio. He also greatly admires the versatile Anna Hepler: “She knows what printmaking can do, which explains some of the beauty in her work.”

Artist Anna Hepler has worked with Wolfe on editions of several of her prints, including Untitled, 2008, woodcut, 18" x 22". “You’re influenced by people whose art you like or respect,” said Wolfe. The more important heroes, he asserted, are the ones in his immediate circle: his son Sean; fellow printer Scott Vile; Andrew Steeves at Gaspereau Press in Nova Scotia; and artist Isak Applin from Queens, New York, who has produced prints and books at Wolfe’s studio. He also greatly admires the versatile Anna Hepler: “She knows what printmaking can do, which explains some of the beauty in her work.”

Asked the requisite question of the day, “How has the pandemic impacted your work?”, Wolfe gave a generally positive report. While workshops were put on hold, he did extra work with Hewitt, who was spending more time in Portland. He has also been helping his son with his downeast operation.

With business picking up again, Wolfe is determined to keep working. “Now is not the time to take it easy,” he said, as the monotype machine steadily punched out type in the background.

Carl Little’s latest book is Mary Alice Treworgy: A Maine Painter (Marshall Wilkes). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

Find out more about David Wolfe at www.wolfeeditions.com.