Michael Torlen was mesmerized by the meeting of granite, sea, and sky on Baker Island in Acadia. Dancing Rocks.03 (from Songs for My Father), 1988, watercolor, 22 by 30 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay York

Michael Torlen was mesmerized by the meeting of granite, sea, and sky on Baker Island in Acadia. Dancing Rocks.03 (from Songs for My Father), 1988, watercolor, 22 by 30 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay York

FOR THE PAST 35 or so years Michael Torlen has never really taken his eyes off the ocean. Wherever he finds himself—Little Cranberry Island, Monhegan, Acadia—he looks seaward. Even in his Westbrook studio, his home base since 2015, he’s apt to be conjuring the Maine coast.

In oil, acrylic, watercolor and various print mediums, Torlen renders waves, rocky shores, various fishing vessels, and the denizens of the deep with a passion born of lifelong connections to the sea. You might say it’s in the stars and in his blood: Born a Pisces, he comes from a Norwegian fishing family. He played in the San Diego shipyards as a kid and later crewed on his father’s tuna-fishing trips. And his grandmother’s house in La Jolla, where he spent time as a child and later while attending San Diego State, was close to the Pacific.

As an Acadia National Park artist in residence, Torlen explored Schoodic Point, coming away with vivid impressions of the wild surf. Moonlight Schoodic Point (from Songs for My Father), 1999, monoprint, 30 by 22 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay YorkTorlen came into his own as a marine painter when he started making summer sojourns to Maine in the 1980s. He and his family stayed on Islesford, one of the Cranberry Isles, where he painted a variety of views, mainly seascapes. One series of watercolors features Baker Island’s Dancing Rocks, great slabs of granite that seem to shift underfoot from the impact of crashing surf.

As an Acadia National Park artist in residence, Torlen explored Schoodic Point, coming away with vivid impressions of the wild surf. Moonlight Schoodic Point (from Songs for My Father), 1999, monoprint, 30 by 22 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay YorkTorlen came into his own as a marine painter when he started making summer sojourns to Maine in the 1980s. He and his family stayed on Islesford, one of the Cranberry Isles, where he painted a variety of views, mainly seascapes. One series of watercolors features Baker Island’s Dancing Rocks, great slabs of granite that seem to shift underfoot from the impact of crashing surf.

As an Acadia National Park Artist-in-Residence in 1998, Torlen, who was inspired by Marsden Hartley, made his way to Schoodic Point on several occasions to study the waves. He also joined the distinguished line of painters mesmerized by Monhegan when he ventured there in 1994. A kind of sea-activated hypnosis took hold and he soon found himself painting the surf as it swelled and pooled and beat against the ironbound island.

Torlen’s romantic view of the sea has undergone some revision in recent years in light of what he cites as “the degradation of the fisheries due to industrial waste, acid rain, and global warming.” These existential threats to our “water planet” are reflected in his most recent series, “Ocean Blues.”

Torlen doesn’t telegraph his concerns. While Warning Skies may allude to the fires brought about by climate change, it also references the sailor’s “red sky at night” adage. These are gorgeous images of sea and survival.

A student of the history of art, Torlen references the old masters in the formatting of the “Ocean Blues” pieces. The central fan shape pays homage to Gauguin and Degas while the encircling images hark back to the studies, or “remarques,” that Delacroix drew in the borders of his lithographs. He also utilizes pochoir, a traditional stenciling process, to create the netting and other pattern effects.

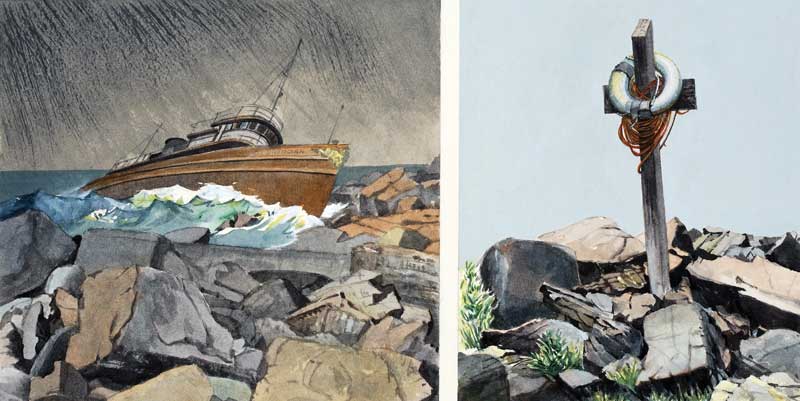

Torlen’s two-part Sheridan and Life Saver (from Sanger Fra Mor), 2007, pays tribute to fishermen lost off Monhegan. Watercolor and gouache, 10 by 20 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay York

Torlen’s two-part Sheridan and Life Saver (from Sanger Fra Mor), 2007, pays tribute to fishermen lost off Monhegan. Watercolor and gouache, 10 by 20 in. Collection the artist. Photo by Jay York

As an artist in residence for the New England Ocean Cluster in Portland, Maine, Torlen is bringing attention to the decline of the saltwater ecosystem through his art, some of which now hangs in The Hus, NEOC’s coworking space on Commercial Street in Portland. He hopes the new “Blue Economy”—sustainable, inclusive, and profitable—will save his beloved seas and fisheries.

Torlen started life in San Diego in 1940. His mother was a painter and interior decorator, his father, a commercial tuna fisherman. They separated when he was quite young and he ended up spending his childhood in different homes and towns in Southern California.

After a year at Oceanside-Carlsbad Junior College studying mechanical engineering, Torlen transferred to San Diego State College where he came under the sway of art professor Bill Bowne. Bowne encouraged him to go to New York where the action was. He soon found himself in the Big Apple, exploring museums, galleries, and the jazz scene.

In his Ocean Blues series, Torlen presents the beauty and power of the sea while recognizing environmental threats to the fisheries. Working (from Ocean Blues), 2020, watercolor, gouache, acrylic and flashe, 13 by 19½ in. Photo by Jay York

In his Ocean Blues series, Torlen presents the beauty and power of the sea while recognizing environmental threats to the fisheries. Working (from Ocean Blues), 2020, watercolor, gouache, acrylic and flashe, 13 by 19½ in. Photo by Jay York

While there, Torlen received notice that Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, had accepted his application. He returned to San Diego to join his father fishing aboard the purse-seiner MV West Point. In the fall he arrived at Cranbrook wearing California clothing. “Most of the winter I was very cold,” he recalled.

Cranbrook’s landscaped grounds, outstanding architecture (including Eero Saarinen-designed buildings), state-of-the-art facilities, and a student body from around the world provided an aesthetic milieu completely new to him. He also got a significant dose of live jazz, joining fellow students on weekend trips to Detroit to hear the likes of John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderley, and Sonny Rollins.

Torlen studied painting and printmaking. Frustrated by subjective critiques and artspeak, he shared his feelings, and his portfolio, with Harold Gregor, an artist-teacher, who provided new insight into his work. As Torlen writes in the preface to his book-in-progress Perception, Drawing and Painting—An Artist’s Handbook, the language Gregor used was “clear and logical, based on perceptual, verifiable experience.”

After earning a BFA at Cranbrook, Torlen returned to San Diego to study privately with Gregor, visiting museums and going on painting trips with him. At his mentor’s urging, he applied to the master’s program at Ohio State where he studied with fine arts professor Hoyt Sherman. His goal: to learn more about painting and pedagogy and eventually teach. Which he did: in 1965 painter Lamar Dodd invited him to join the University of Georgia’s art department.

In 1970 Torlen left his tenured teaching position at UGA to move to New York City. He lived in SOHO, worked with artist Richard Artschwager in his workshop on Canal Street, and did construction for artists building working/living spaces in lofts.

Torlen categorizes his work from this period as “Spiritual Abstraction.” He studied a wide range of esoteric subjects, including Tantric art, astrology, numerology, the Kabbalah, alchemy, and other pre-industrial theories. For a time he lived in an ashram.

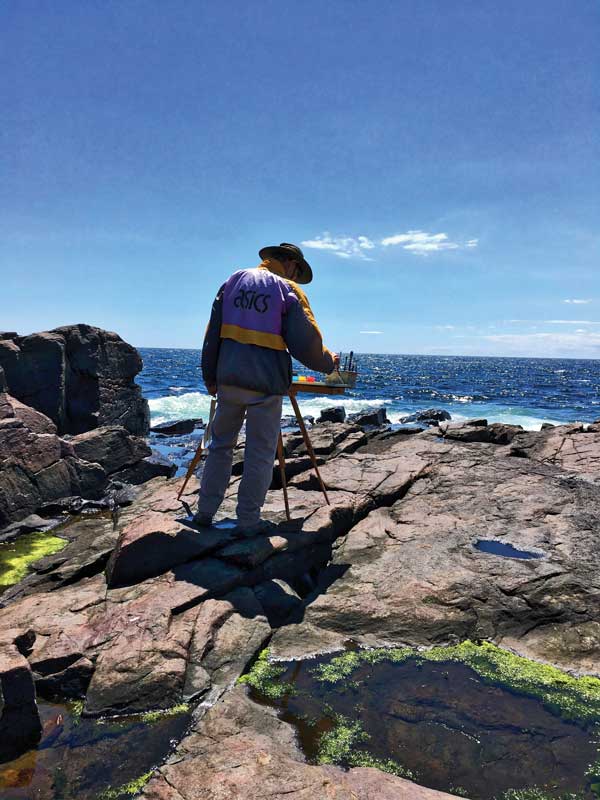

Michael Torlen painting near Lobster Cove on Monhegan Island. Photo by Eleanor Phillips BrackbillIn 1972, Torlen returned to teaching, joining the arts faculty at Purchase College. His artistic direction took a turn when he started to take on more administrative responsibilities, serving as presiding officer of the faculty in the early 1980s and then interim Dean of the Visual Arts Division. During this period he started to visit Maine and began researching American landscape painting.

Michael Torlen painting near Lobster Cove on Monhegan Island. Photo by Eleanor Phillips BrackbillIn 1972, Torlen returned to teaching, joining the arts faculty at Purchase College. His artistic direction took a turn when he started to take on more administrative responsibilities, serving as presiding officer of the faculty in the early 1980s and then interim Dean of the Visual Arts Division. During this period he started to visit Maine and began researching American landscape painting.

He also took up watercolor, and while the first results were “awful,” he stuck with it. He shares a saying apropos of his progress with the medium: “If you want to learn watercolor, you have to be prepared to throw the first five hundred away.”

For several summers Torlen stayed on Little Cranberry Island, a.k.a. Islesford, painting the rocks and sea in the open air. The rest of the year he worked in the studio, painting in oil, making monoprints, and developing his watercolor skills. He painted from photographs and worked with a limited palette for several years.

Over the past several decades, Torlen has worked on two major series, “Sanger Fra Mor (Songs for My Mother)” and “Songs for My Father.” Both incorporate sea imagery, but also feature other subjects, including dancers, rodeo cowboys, Pegasus, and the trickster god Hermes. And the palette is not restricted: These collage-like pieces, with juxtapositions of diverse imagery, are brilliant and bright.

Another ongoing series, “Memento Mori,” arose out of a cancer episode in 2016. These meditations on sex and death, which reference “the wonders of medical technology, cancer, and healing,” employ a palette of “chemo colors” along with techniques from monoprinting—layering, transparency, and pochoir.

The series gained a new relevance for Torlen during the pandemic. “Life in our modern world feels Neo-Medieval—fragile, dangerous, and uncertain,” Torlen wrote in a statement for the Union of Maine Visual Artists’ Maine Arts Journal last spring.

Some solace can be found with the sea. When set up with easel on coastal ledges, Torlen finds the sound of the surf hypnotic.” There is something “very ancient” in this meditative experience. “It touches my soul,” he said. His remarkable art reflects that connection and that seaborne spirit.

✮

Carl Little lives and writes on Mount Desert Island. He is a regular contributor to this magazine and to Working Waterfront, Art New England, and Hyperallergic.

Torlen will exhibit his “Ocean Blues” series at Archipelago in Rockland July 16 through September 25, 2021, as part of a group show titled “Currents and Channels: Four Coastal Maine Painters.” (The other artists are Kaitlyn Miller, Michele O’Keefe, and Leecia Price.) Torlen is represented by Lupine Gallery on Monhegan Island. You can view more of his work at www.michaeltorlen.com.