Great white sharks have been cruising Maine waters for hundreds of years. Their increasing population in the Gulf of Maine is due in part to booming populations of seals—the shark’s primary food. Shark researcher Greg Skomal took this photo of a white shark off Cape Cod. Photo by Greg Skomal

Great white sharks have been cruising Maine waters for hundreds of years. Their increasing population in the Gulf of Maine is due in part to booming populations of seals—the shark’s primary food. Shark researcher Greg Skomal took this photo of a white shark off Cape Cod. Photo by Greg SkomalJESSE MCPHAIL, 40, has been lobstering in downeast Maine since he was 20 years old. Last October, he was checking lobster traps from his fishing boat Wind-N-Sea, within sight of Eastport’s Chowder House, when he and his stern man, Alex Matthews, approached an oddly bobbing lobster buoy. The usually visible balloon attached to his buoy was zigzagging a few feet underwater.

Lobsterman Jesse McPhail of Eastport, Maine, moments after removing line that had entangled a juvenile white shark and before he released the live 14-footer back into the ocean off Eastport. Photo courtesy of Jesse McPhail“I figured a tuna had gotten tangled in my line,” McPhail said. “So, we hooked the line to an electric pot hauler and started lifting. As the heavy fish rose, we were shocked to see a great white shark’s head approaching the surface.”

Lobsterman Jesse McPhail of Eastport, Maine, moments after removing line that had entangled a juvenile white shark and before he released the live 14-footer back into the ocean off Eastport. Photo courtesy of Jesse McPhail“I figured a tuna had gotten tangled in my line,” McPhail said. “So, we hooked the line to an electric pot hauler and started lifting. As the heavy fish rose, we were shocked to see a great white shark’s head approaching the surface.”

The lobster pot line had somehow gotten looped around the shark’s head.

“It was alive, but no way were we going to untangle the line in the water.”

McPhail and Matthews quickly deployed his second pot hauler anchored to the vessel’s roof, tied a rope around the shark’s tail, and lifted the 14-foot animal out of the water.

“Hanging upside down in the air,” McPhail continued, “the shark played dead. So we lowered it onto the railing and carefully untangled the lobster line.”

The fishermen snapped several photos, lowered the shark into the water head first, untied the tail line, and watched it swim into the deep blue.

Shark researchers in Massachusetts who examined McPhail’s photos concluded that the great white was a juvenile female, likely in her late teens.

A few months earlier, Kingsley Pendleton of Deer Island, New Brunswick—less than ten miles northeast of Eastport—was boating with his family in Lord’s Cove when he too had a close encounter with a great white shark.

“The shark was a half mile from our boat and swimming toward us against the tide in choppy water. Initially, I wasn’t sure what it was. But as it came closer I could see a very large triangular dorsal fin, and knew then that it was a sizable great white and not a basking shark. It exhibited the characteristic demarcation line on its flanks transitioning from a dark gray back to a creamy white underside.”

Pendleton and his family were drifting in calm waters in his 19-foot Carolina skiff when the shark circled the boat.

“By now, my nervous wife and daughter were urging me to start the motor, which I did, aligning the boat alongside the shark. When its snout was even with the bow, I looked back and could see its tail extend about a foot beyond the stern. Aware that my shallow skiff weighs about 1,000 pounds, I said to myself, ‘If that 4,000-pound shark threw itself onto my boat, as it often does to grab seals sunning on ledges, we’ll be in deep trouble.’ It circled the boat a few more times before disappearing.”

Since 2012, Massachusetts shark researcher Dr. Greg Skomal has attached acoustic tags to more than 120 white sharks. Several of his tagged sharks have been recorded in Eastport, Maine. Skomal took this photo of a shark off the coast of Guadalupe, Mexico. Photo courtesy Greg Skomal

Since 2012, Massachusetts shark researcher Dr. Greg Skomal has attached acoustic tags to more than 120 white sharks. Several of his tagged sharks have been recorded in Eastport, Maine. Skomal took this photo of a shark off the coast of Guadalupe, Mexico. Photo courtesy Greg Skomal

Pendleton’s unofficial 20-foot white shark was even larger than the 17-foot 2-inch female white shark captured, tagged, and released last October by OCEARCH—a science organization committed to collecting and sharing oceanic data—off the south coast of Nova Scotia. She weighed 3,541 pounds. Scientists estimated that she was at least 50 years old and likely had produced upwards of 100 young during her lifetime. By November, she was reported swimming off the New Jersey coast.

Dr. Gayle Zydlewski, director of the Maine Sea Grant College, is among the many scientists monitoring great white sharks in the Gulf of Maine. In 2018, she attached a cylindrical fish tag audio receiver to a buoy line in Western Passage, Eastport—close to where McPhail released his ensnared white shark. Zydlewski’s receiver recorded two tagged white sharks—a juvenile male and a juvenile female—each 11 feet in length and both tagged offshore from Cape Cod. Dr. Greg Skomal, a shark researcher in Massachusetts who has attached acoustic tags to more than 120 white sharks since 2012, had tagged them both. In 2019, Zydlewski’s receiver recorded six white sharks off Eastport. Five had been tagged by Skomal; the other was a 4.5-foot young-of-the-year male tagged by National Marine Fisheries Service biologists off Long Island.

In July 2020, the fatal shark attack of a 63-year-old woman in the waters off Bailey Island prompted the Maine Department of Marine Resources to partner with Zydlewski, Skomal, and the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy to better understand shark ecology and movements in Maine waters.

“The presence of great white sharks along our coastline precedes record keeping,” said Jeff Nichols, communications director of the Maine DMR. “However, last summer’s tragic death of a swimmer was a first for the state of Maine,” he added.

Most unprovoked shark attacks are the result of a shark mistaking a human for a seal. To date, Maine DMR has installed acoustic recorders near Bailey Island and Popham Beach to monitor shark movements and habitat preferences. “Learning how and when sharks move through Maine waters,” said Nichols, “will hopefully allow us to better protect salt water recreationalists, as well as sharks. At the moment, we’re recommending people avoid swimming among schooling fish and seals, especially during the summer months, which coincide with peak shark activity in Maine.”

Increasing great white shark populations in recent years can be traced back to the passage of two federal laws. First, in 1972, the Marine Mammal Protection Act provided legal protection for seals in U.S. waters. Historically, seals were indiscriminately killed by New England fishermen who considered the mammals a nuisance and a competitor for fish. Seal bounties, dating back to colonial times, resulted in local extirpation in Maine and elsewhere. When the law was enacted, a University of Maine survey documented fewer than 5,000 harbor seals and zero gray seals along the state’s coast. Today, in Maine alone, the estimated combined population of both phocids is near 100,000. More seals, a favorite prey of sharks, means more sharks.

Second, in 1976, the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act was enacted to halt overfishing, rebuild depleted fish stocks, and ensure long-term biological and economic sustainability of marine fisheries. In 1997, an amendment was added designating Atlantic great white sharks a federally protected species, paving the way for a partial recovery of shark populations. According to the National Marine Fisheries Service, the Atlantic great white shark population now stands at 69 percent of what it was in 1961, a significant increase since the 1980s. Shark population growth, though, lags behind booming seal populations because the predators grow more slowly. Females don’t reach sexual maturity until their teens, and then they only produce two to ten pups, possibly every other year, after 12 months of gestation.

“As the white shark population rebounds and seal populations rebound,” Dr. Skomal said, “this predator-prey relationship is going to re-emerge anywhere these two species overlap.” The dramatic shark-seal battles, increasingly captured on smart phones (search for Jolly Breeze Whale Watching Company’s shark videos), underscores the resiliency of the Gulf of Maine following decades of indiscriminate commercial fisheries and marine mammal exploitation.

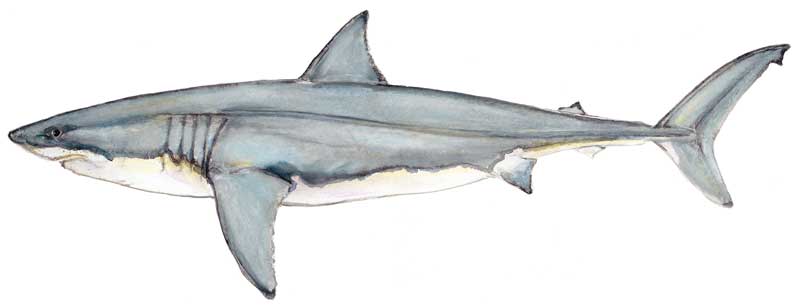

Diagnostic features of great whites include a long, conical snout; large, broad, triangular dorsal fin; a sharp line of demarcation between gray upper body and whitish underside; and large, erect, triangular and serrated upper teeth. Great whites have no known natural predators except, on rare occasions, killer whales. It’s the world’s largest predatory fish with adult females reaching 20 or more feet and weighing close to two tons. Illustration by Karen Talbot

Diagnostic features of great whites include a long, conical snout; large, broad, triangular dorsal fin; a sharp line of demarcation between gray upper body and whitish underside; and large, erect, triangular and serrated upper teeth. Great whites have no known natural predators except, on rare occasions, killer whales. It’s the world’s largest predatory fish with adult females reaching 20 or more feet and weighing close to two tons. Illustration by Karen Talbot

A broad spectrum of shark enthusiasts, from scientists to whale watching boat captains, are observing a seismic shift in public opinion on sharks. Once widely demonized as “man-eaters,” sharks are quickly gaining rock star status. Two summers ago on a Campobello Island Cruises Whale Watch boat, I overheard twin 8-year-old girls—each wearing identical “Save Our Great White Sharks” sweatshirts—quiz Captain Mackie Greene, “Did you know that great whites are endothermic?” He answered yes and then winked at me and said, “More and more clients, like these girls, are asking if I can show them a shark.”

Pendleton is also a passionate fan of the apex predator. “I’ve boated for many years,” he said, “and have seen lots of whales, porbeagles (mackerel sharks), basking sharks, and thresher sharks. Seeing a great white shark, though, is special. My wife jokes that I’ll tell anyone about our encounter with a large great white last August. She’s right, because it sure made my summer.”

✮

Writer Ronald Joseph is a retired wildlife biologist. He lives in central Maine.

For More Information

For more on sharks in the Gulf of Maine, see our story from 2016