All photos courtesy Peter Van Allen

Noah Van Allen tests out a wooden bellyboard at Scarborough Beach in Maine. The board was built by Grain Surfboards of York, Maine.

Noah Van Allen tests out a wooden bellyboard at Scarborough Beach in Maine. The board was built by Grain Surfboards of York, Maine.

Four of us we were in a J/22 in Casco Bay—two parents rusty in their sailing skills, our grade-school-aged son, and a Sail Maine instructor.

Our son, Noah, at the time nearly 9 and making the transition to fourth grade, was at the helm. Sailing was just one of the things he was learning in 2020, a year defined by adaptation, apprehension, exhilaration, change, and growth.

The instructor made a comparison between running downwind to cruising on a skateboard. “Do you skateboard?” she asked Noah.

Even through his pandemic face mask, we could see his face light up. Skateboarding was just one of the sports he’d gravitated to in 2020.

Just since March 2020, when the pandemic lockdown first started, he’d already gone through a gauntlet of new sports: skate skiing and snowboarding, then skateboarding, then as the water warmed up, sea kayaking, bellyboarding, and surfing. As the water started cooling down again, he gravitated to mountain biking and fat-tire biking.

With no school, no organized sports, and no summer camps, we had a lot of time on our hands.

Life in the pod

For Noah, the pandemic has been about being with family nearly constantly, a sink-or-swim proposition in itself, interspersed with short breaks with a small cadre of friends in our “pod.” My wife Jen shouldered the homework and schooling-from-home, while also juggling her own work.

My role was a bit less well-defined, but as the pandemic went on, Noah and I found ourselves in the workshop, building stuff. Initially, there were snowboards—crude wooden planks without rocker or the necessary kicked nose—that we tested on neighborhood hills. The first boards were plywood or simple designs. Eventually we started gluing pieces together, trying to create kick noses with hand planes.

The more we worked on snowboards, the more they reminded me of skateboards from my youth in the 1970s, particularly those of board pioneer Tom Sims, who brought a surfing and skiing mentality to his skateboards. The skateboards Sims built were more similar to what are today known as longboards, for long, flowing turns and cruising.

I suggested to Noah that we put wheels on one of our snowboards. He didn’t like the idea of messing up one of the half dozen or so snowboards we’d built.

Noah and Peter Van Allen spent part of the pandemic building a range of snowboards, skateboards, and a surfboard. Pictured here are some of the skateboard experiments, and the builders, sporting grip-tape “mustaches.”

Noah and Peter Van Allen spent part of the pandemic building a range of snowboards, skateboards, and a surfboard. Pictured here are some of the skateboard experiments, and the builders, sporting grip-tape “mustaches.”

A DIY education

So we started building skateboards. At first they were simple pine, or sections of pine glued together, cut with a jigsaw and planed and sanded into a basic “fish” shape. But that was just the beginning of a journey, building and testing more than a dozen skateboards.

We’d glue them up, shape them, sand them, and stain or paint them. Initially, we ordered wheels, trucks, and bearings on Amazon but then, as we discovered independent shops in California and North Carolina, we ordered directly from them.

We’d do late-afternoon test rides, suited up with pads on elbows and knees, wrist guards, and helmets. As Noah’s skills and confidence grew and my own skateboarding skills—dormant for several decades—reemerged, the hills we rode got bigger until we finally found our nirvana: a vast, sloping parking lot with fresh asphalt and almost no regular car traffic.

The skateboards started as basic shapes. We cut some out of plywood that were light and fun to ride. In one case, an experimental board we’d made of lightweight plywood failed before we even got to try it. Attempting to put my pads on, I sat on the skateboard, and the board broke in half—breaking my son’s heart in the process. Yet, like the Wright Brothers, those initial failures just fueled our mentality to develop, build and test new boards.

Noah Van Allen planes a wooden snowboard built in the family’s backyard shed. He typically worked with the hand tools, while his dad ran the power tools.

Noah Van Allen planes a wooden snowboard built in the family’s backyard shed. He typically worked with the hand tools, while his dad ran the power tools.

Art out of sawdust

The skateboards evolved from there. We quickly moved beyond the plywood and pine boards. We sourced white oak, mahogany, and other hardwoods from Day’s Hardwoods in Freeport, or salvaged hardwood strips we could find on the scrap pile at Fat Andy’s flooring in North Yarmouth.

We had a good workshop to hatch our skateboards. The year before I’d built a shed in which to build a dory. It was well outfitted with a table saw, miter saw, jig and circular saws, power planer, power sander and hand tools.

Power tools were my domain, while Noah took over much of the hand plane work and sanding.

We’d lay out strips of hardwood, often alternating lighter and darker woods, then glue and clamp them together. Once the glue had set, I’d hone down the thickness with a noisy Makita power planer. At that point, we’d take measurements, determine where we wanted the center line on the board, then draw an outline of the board. As we got more into it, we’d use other skateboards, even production boards like an old Sector 9 skateboard, as templates for all or part of the shape we wanted. Once we outlined the shape, I cut it out with the jigsaw, then Noah would plane and sand it.

Often, during the early stages of building a board, Noah made no bones about expressing his misgivings about the rough state of things. At one point, with the supreme tact only a 9-year-old could muster, he blurted out, “This is horrible!” But as the shape slowly evolved out of the rough wood, his mood would improve.

One day when he was inside having lunch, I finished a skateboard in clear polyurethane. He came out and saw the gleaming board, the wood grain highlighted by the finish, and his eyes lit up. All that was left was to drill the holes and attach the trucks and wheels.

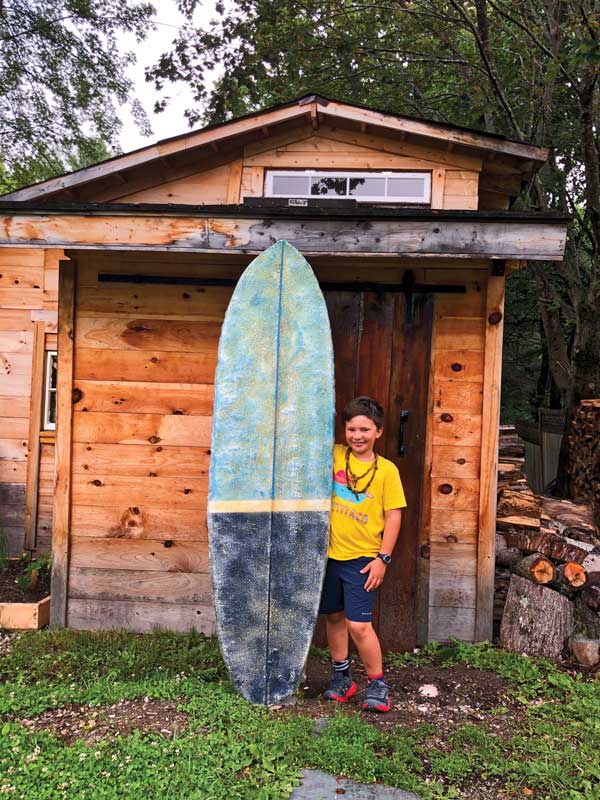

Before we’d test them, we’d do a photo in front of the shed workshop and post it on Instagram, where we connected with legions of DIY skateboard makers from around the world.

After each board was completed, the father and son took a photo in front of the workshop/shed. The skateboards pictured were built with hardwoods laminated together then shaped with a combination of power tools and hand tools. Noah rode the board in his hands nearly every day in the summer.

After each board was completed, the father and son took a photo in front of the workshop/shed. The skateboards pictured were built with hardwoods laminated together then shaped with a combination of power tools and hand tools. Noah rode the board in his hands nearly every day in the summer.

Transition to water

In the early summer, we tried transferring our skills to building a foam-and-fiberglass surfboard, but we didn’t like working with the messy foam dust, and the heavy filtration masks and goggles it required. That board was a disaster. I’d taught Noah to surf on my own surfboard, and his skills were quickly improving, making our own venture into “shaping” even more frustrating.

There was an interesting turn of good fortune toward the end of the summer.

We gifted one of the skateboards we’d built to Noah’s friend Henry, who regularly joined us in our late-afternoon skate sessions. Shortly after, our karma came back around. I’d been in touch with Mike LaVecchia, owner of Grain Surfboards in York. He mentioned that the family of a late customer who’d bought a number of Grain surfboards and a bellyboard, now wanted to pass the boards along to young people. Mike offered Noah a gorgeous hand-built bellyboard, known by the Hawaiian word paipo (pronounced PIE-po). It was 4' 6" long and built out of cedar strips with an internal “chamber” system for flotation. Mike had built the board in 2009, and it was stunning, still in pristine condition.

Board building comes with a lot of trial and error. In this case, the surfboard, built from a kit, was mostly an error. The foam and the resin didn’t work well together, resulting in an uneven surface—and a failed “shaping” experience. Still, note the smile.

Board building comes with a lot of trial and error. In this case, the surfboard, built from a kit, was mostly an error. The foam and the resin didn’t work well together, resulting in an uneven surface—and a failed “shaping” experience. Still, note the smile.

The skateboards had defined our early summer, but now we were tackling waves, Noah on his paipo and me on a Grain bellyboard I’d shaped several years earlier.

Even on big waves that throttled us, there was the satisfaction of what we’d learned and the journey we’d taken.

✮

Peter Van Allen is editor of Mainebiz. He has three kids and lives with his wife Jen and son Noah in Yarmouth. He is a lifelong surfer, paddler and, once again, enthusiastic skateboarder.