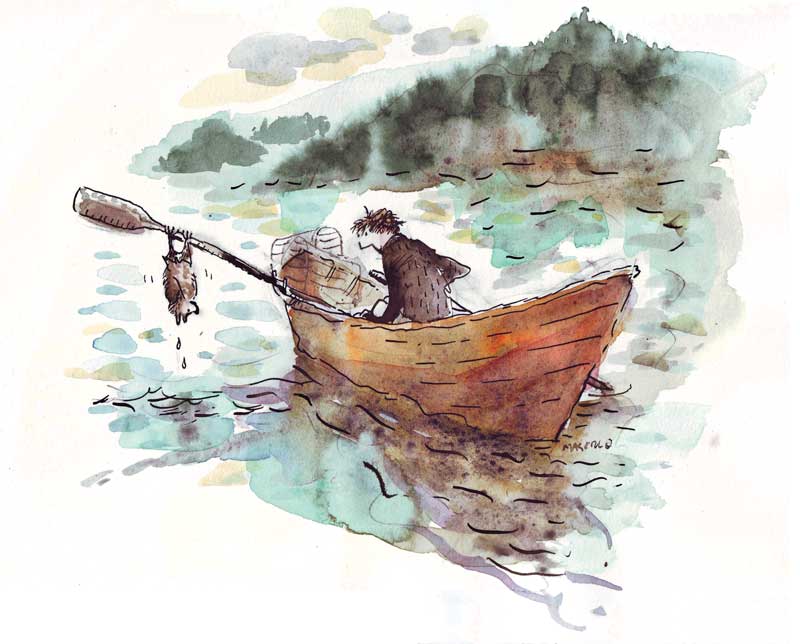

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

One evening before a storm, all the water seemed to drain out of the harbor. Rocks that were coated in pink coral and the hold-fasts of storm-torn kelp got a chance to breathe air, maybe for the first time. Then the big swell filled the harbor again, well above the tide line. The sea touched sun-baked gray rocks that seldom tasted salt water. It was like a mini-tsunami, but more fascinating than deadly.

You have to be really lucky to see something like that, or spend a lot of time in a place. For me that place was Haycock’s Harbor, a narrow fjord that slices into the Maine coast close to Canada—far from yacht clubs and waterfront dining. Haycock’s is a half-tide harbor, you can only get in and out twice a day for six hours at a time—three hours before high tide and three hours after. The handful of people who work out of Haycock’s Harbor always become very tide conscious; they watch the phases of the moon and plan accordingly.

It’s not a place you can just go to. On another rare evening a sailboat hove to in Grand Manan Channel, sails luffing just off the mouth of the harbor. The solo sailor hailed me as I rowed by with a few bags of periwinkles—wrinkles, as we call them. He had shaggy black hair and ragged clothes, and he stood with one hand on the shrouds. I looked over the boat, a thirty-something foot wooden ketch named Atlantic Parrot, painted a fading green and looking a bit rust streaked and sea-worn.

“Do you know the way in here?” he called.

I shrugged. “Sure.”

“Can you guide me in?”

I looked at the harbor, and considered how to do that—me in a little dory, him in his big boat. “I’ll come aboard,” I said, and he agreed. We furled his sails and he started his engine. I started off giving him directions, but then I ran to the bow and with an upraised arm, showed him which way to steer.

The entrance to Haycock’s Harbor begins with a passage between two jaws of jagged rocks into the outer harbor. There a couple of lobstermen keep moorings to use while they wait for the tide. I piloted the boat to the right of the big plastic balls floating on the surface, and hugged the right-hand shore to get over the deepest spot in the bar at the head of the outer harbor, and then up through the gut to a line of weir stakes driven years earlier by Colie Morrison. I’d rowed past and talked to Colie when he and his brother Maynard were driving those stakes. Colie had an awkward eye that went adrift when he looked at you so you had to focus on just the one he had trained on you. A more amiable man you’ll seldom meet. He was a first-class rigger and a master welder. “I can mend anything but a broken heart,” he used to say. I couldn’t help thinking about him as the motley sailor—Steve, he’d told me—backed the engine and I threw a clove hitch round one of those stakes.

“You’ll have to work this out with Wayne,” I said, pointing to the lobsterman’s skiff. “He’s got a 36-foot lobsterboat he ties right there.”

I jumped back in my dory, cast loose and rowed up to my mooring at the very head of the harbor.

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

In those days I was a wrinkle picker and seaweed harvester, and I hauled 50 wooden lobster traps by hand. Working the big tides meant early mornings around the new moon and the full. I would row down the length of the harbor in the pre-dawn cool of summer mornings, listening to the echo of the hermit thrush’s song between the steep sides of the harbor. I would row out onto the deep ocean swells. Along that part of the coast it seems the offshore world comes closest to land and it’s not unusual to see a gannet, puffin, or even a shearwater.

One morning, just as I rounded a point into neighboring Sandy Cove, a minke whale rose up and blew right at the tip of my oar. “If I’d had a harpoon I could have got it,” I later said, thoughtlessly, to a woman whose eyes widened at the idea. But I was a sea reiver in those days, working the outside shore and taking anything I could find. “I know every rock by name between Moose River and Baileys Mistake,” I used to say. “I can row the length of the coast in a thick a fog and know exactly where I am by the sound of how the waves break.”

That’s how I navigated, by sound, like a bat. One morning, as I rowed out into the deep water after a swift passing thunderstorm, I looked behind me and saw something odd flapping on the surface. At first I thought it might be a bit of kelp being worked by the tide, but the motion was too regular. I backed water to come closer, and saw it was a bat, swimming hard for the side of my dory. I scooped him aboard with my hand. “Damn. It’s your lucky day,” I said. As I rowed on to Moose River he licked himself dry and then crawled up under the rail. He was still there after I finished the tide, but as the flood bore us back toward Haycock’s, I saw a bat circle me and head toward land. I looked under the rail and the bat was gone.

I was rowing home on another day, another tide, and came through the gut at Haycock’s, going a good four knots. The flood spit me out into the pool and Wayne was there on his boat banding lobsters with his sons. “When you going to put a motor on that thing?” he asked. “You’re going to end up over on Grand Manan like Billy and Floyd.”

“They had a motor,” I said. Everyone knew the story of Wayne’s brothers, Billy and Floyd. They broke down and got blown across the channel to the island of Grand Manan, Canada. Billy had to scale the fortress-like cliffs on the west side of the island and get help for Floyd, who’d gotten hurt when they crashed ashore.

“Besides,” I said. “I’m a strong rower.”

“I know that,” said Wayne.

“And I go out with the tide and come back with the tide. I work these shores like harvesting a garden and just about every cent I make stays in my pocket. If I had a motor I’d have to pay $1,000 for it, buy gas, and register my boat. Then I’d have to pick more wrinkles. I’d have to go farther to find them, and bump up against other wrinkle pickers and we’d have turf wars and nasty feelings. Better this way.”

He laughed. “Seems like a lot of work,” he said.

“I wish they would make a law,” I said. “Where if you’re willing to row a dory, you can do whatever you want without a license, haul lobster traps, fish for halibut, pick wrinkles, whatever.”

Wayne wasn’t too sure about the lobstering part. They say the hunter becomes like their prey, and lobsters are very territorial.

“Anybody who wants to try and make a living rowing on the ocean shouldn’t need to ask permission,” I said, but the idea never gained any traction outside my imagination.

In the years that have followed, the wrinkles disappeared, Steve settled down, the Atlantic Parrot rotted on land, the price of a lobster license went beyond what anyone hauling 50 traps by hand could pay—and I’ve gotten older. But there was a time in the 21st century when a person could make a living from a rowboat, counting mostly on intimacy with place and low expectations. I’m sure I wasn’t alone. Probably there were others finding little niches of livelihood along the coast, and learning those places so well they visit them in their dreams, but nobody writes those stories down.

Paul Molyneaux lives in East Machias and has written about commercial fishing in the New York Times and other publications. He is the author of A Child’s Walk in the Wilderness, published in 2013 by Stackpole Books.