One of Earle Shettleworth’s first efforts at historic preservation involved meeting with former Gov. Percival Baxter, seeking to enlist his help in saving the Heseltine School on Ocean Avenue in Portland. Photo courtesy Earle Shettleworth, Jr.

One of Earle Shettleworth’s first efforts at historic preservation involved meeting with former Gov. Percival Baxter, seeking to enlist his help in saving the Heseltine School on Ocean Avenue in Portland. Photo courtesy Earle Shettleworth, Jr.  A young Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. in 1960, the year he first met personally with Governor Baxter and Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. as he looks today. Left photo courtesy Earle Shettleworth, Jr., and right photo by Bob Mitchell.

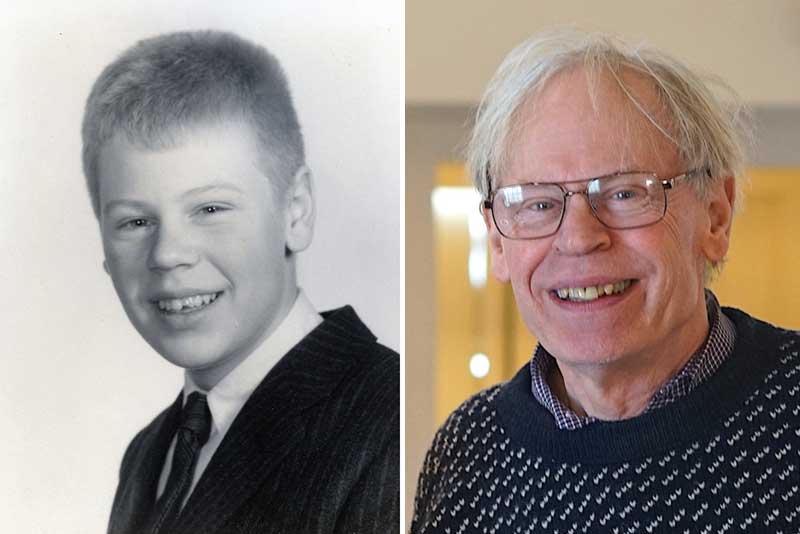

A young Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. in 1960, the year he first met personally with Governor Baxter and Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. as he looks today. Left photo courtesy Earle Shettleworth, Jr., and right photo by Bob Mitchell.

Born in Portland in 1948, I grew up on Hersey Street in the city’s Baxter Boulevard neighborhood. The Heseltine School on Ocean Avenue was within walking distance of my home, and I started kindergarten there at the age of 4 in 1952. Constructed in 1867, this Victorian brick building was little changed since its enlargement in 1902. Its entrance hall featured a grand staircase to the second floor. Each of the two floors contained three classrooms that were time capsules of dark woodwork, rows of stationary wooden desks with glass ink wells, slate blackboards, patriotic prints, and plaster busts of Washington, Lincoln, and other famous figures. For a child discovering his love of history, this period interior awakened a fascination for the past.

I attended the Heseltine School until midway through the second grade in 1956. That January the school closed, and its faculty and students moved to the new Percival P. Baxter School on Ocean Avenue and Walton Street.

At 79 years old in 1956, Percival Baxter was Maine’s most respected citizen, having served as governor from 1921 to 1925. Between 1931 and 1955, he created Baxter State Park by giving Mount Katahdin and 200,000 acres surrounding it to the state. Baxter was deeply appreciative that his native Portland was naming a school in his honor, and he participated in its dedication, a ceremony attended by city officials, teachers, students (including me), and parents. Thus, at seven years old, I first saw Governor Baxter and heard him speak.

Baxter became a presence at the school that bore his name, both in the photograph of him that hung in the entrance hall and in personal visits. At least once a year his chauffeured Cadillac with its famous “111-111” license plate would park in front of the school, and he would be taken by Principal Katherine Jordan to each classroom

to talk with the students. During a Christmas visit to my class one year, he asked the Jewish children to explain how they celebrated their holidays. This ecumenical approach reflected the governor’s knowledge that many Jewish students attended the school and that their religious practices should be respected equally with Christian ones.

During my grammar-school years, my enthusiasm for history continued to grow, fostered by reading, visiting historic sites, and collecting antiques. When I reached the sixth grade, I began to research the history of the Heseltine School as one of the oldest buildings in my neighborhood. My interest in the school led me to believe that it should be preserved. To that end, I sought the advice of Governor Baxter, reasoning that if he could save a mountain, he would know how to save a building.

This image in the collection of the Portland Public Library shows former Gov. Percival Baxter in 1923 with Reverend Hammond I. Peterson, at the Bible Society of Maine offices. Baxter is pointing to his handwritten entry in the unique Bible made entirely by Maine people in 1923. Gannett Collection, Portland Room, Portland Public Library

This image in the collection of the Portland Public Library shows former Gov. Percival Baxter in 1923 with Reverend Hammond I. Peterson, at the Bible Society of Maine offices. Baxter is pointing to his handwritten entry in the unique Bible made entirely by Maine people in 1923. Gannett Collection, Portland Room, Portland Public Library

In May 1960, as the school year ended, I summoned the courage to make a Saturday morning appointment with him. Located on the top floor of the Trelawney Building, Baxter’s large office overlooked Longfellow Square and State Street with its canopy of elms. As I was ushered into the room by his secretary, I was greeted by a tall, thin, courtly 83-year-old gentleman. After shaking my hand, he pointed to a glass paperweight on his desk that pictured both his father James P. Baxter and the building that the senior Baxter had constructed as a public library for Portland in 1887-88.

Governor Baxter related that when he was my age—11 in 1887— he attended the cornerstone laying of the Baxter Building. Weary of the long speeches, young Percival began to explore the uncompleted structure of the library, climbing to a point where he could not get down. His cries for help forced James P. Baxter to interrupt the program to call the fire department to rescue his stranded son.

As for the purpose of my visit, Governor Baxter explained to me that the City of Portland did not have the means to save its former school buildings. (The concept of adaptive reuse was still in the future.) Shortly after the visit, the governor contacted my principal and sixth grade teacher Katherine Jordan to tell her that he had enjoyed talking with me.

As my interest in local and state history continued to develop in junior high school, I made another appointment to visit Governor Baxter on a Saturday morning in February 1963. I brought a copy of the booklet for the dedication of Baxter Boulevard, an occasion at which he had spoken shortly after leaving the governorship in 1925. He agreed to my request to autograph the booklet, placing a pen, a pencil, a ruler, and an eraser on his desk. On the title page of the booklet, he carefully ruled three light pencil lines, wrote the words “To Earle Shettleworth/With Regards of/Percival P/ Baxter,” let the ink dry, and then erased the pencil lines.

During that visit I asked Governor Baxter several questions about Maine politics in the 1920s. When I mentioned Gov. Ralph Owen Brewster’s name, he declined to comment, saying that whatever had transpired between them was now in the past and best left unsaid. (Brewster succeeded Baxter as governor, and with the help of the Ku Klux Klan sabotaged Baxter’s run for the U.S. Senate. When Brewster made his own run for the Senate seat, Baxter denounced him as a member of the Klan.) As I rose to leave, Governor Baxter took me to a large framed photograph of Mount Katahdin and asked, “Have you seen my mountain?” He also gave me an autographed postcard of Katahdin.

As I finished Lincoln Junior High School in the spring of 1963, Elizabeth Ring invited me to join the Maine Historical Society, and at 14, I began my longtime association with the organization. One of Maine’s foremost historians, Miss Ring headed the History and Government Department at Deering High School, where I enrolled in her American history class that fall.

She encouraged my fellow Deering student Peter N. Kyros, Jr. and me to become involved in the historical society, and she introduced me to Christopher P. Monkhouse, another young Portlander who shared my interests. In the fall of 1964, Peter, Christopher, and I created an exhibit on Maine politics in the second-floor lecture hall of the society’s library. Our mentor Miss Ring wrote on our behalf to all the living governors, senators, and congressmen to request donations of their campaign memorabilia for the display. Governor Baxter responded with the gift of a large Herbert Hoover button from the 1928 presidential campaign. What made this pin unusual was its attached red ribbon proclaiming the names Hoover and Baxter in gold letters, reflecting the governor’s favorite son status at the Republican National Convention, as well as Baxter’s friendship with Hoover.

At the age of 16 in June 1965, I began working as a summer reporter for the Portland Evening Express. In addition to such routine assignments as writing obituaries and the daily police report, I was given the opportunity to publish a series of articles entitled “Portland’s Heritage,” which featured the city’s significant homes and buildings. The preservation organization Greater Portland Landmarks had been formed the year before, and the newspaper’s editors believed that readers would be interested in learning about the city’s past. The series was so well received the first year that it continued for the summers of 1966 and 1967 for a total of 52 articles over three years.

One of my 1966 articles documented the James P. Baxter House at 61 Deering Street, where Governor Baxter was born in 1876. To illustrate the piece, I called the governor to ask for pictures of his former home. He invited me to his house on West Street to view a remarkable painting of the interior of his father’s Deering Street library in 1878, showing a small group of family members, including himself at age two. The picture hung over a living room fireplace decorated by his mother’s painted tiles, which he had removed from the Deering Street house.

Governor Baxter also showed me a large oil portrait of his father with a view of the Portland Public Library, symbolizing his father’s gift of the Baxter Building to the city. The governor had placed a mirror directly across from the painting, commenting to me that the reflection of the portrait created a lifelike image of his father.

A 1967 article in the “Portland’s Heritage” series recounted the role of James P. Baxter in the development of the Portland Park System during his six terms as mayor. Governor Baxter was so appreciative of this recognition of his father that he visited the newsroom to thank me in person. Heads turned in amazement that day as this 90-year-old living legend made his way to the desk of a 19-year-old summer reporter. It was the last time that I saw him. Two years later he died, at the age of 92, and his ashes were scattered over his beloved Mount Katahdin.

Shortly after my 21st birthday in August 1969, Gov. Kenneth M. Curtis appointed me to the Archives Advisory Board, beginning what has now been more than a half-century of public service to the State of Maine in the field of history. Throughout the years, I have been inspired by Governor Baxter’s example of vision and generosity and have cherished having known him.

A native of Portland, Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr. directed the Maine Historic Preservation

Commission from 1976 to 2015 and has served as Maine State Historian since 2004.