Illustrations by Caroline Magerl

“Have you ever counted deer dung?” Biologist Gene Dumont posed the question moments after we’d met. Before I could say no, he added, “Follow me. Your on-the-job training begins right now.”

“Have you ever counted deer dung?” Biologist Gene Dumont posed the question moments after we’d met. Before I could say no, he added, “Follow me. Your on-the-job training begins right now.”

It was April 4, 1978, my 26th birthday and my first day of employment as a wildlife biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. I was hired primarily to collect deer population data by counting their dung piles, known as “deer pellet-group surveys.”

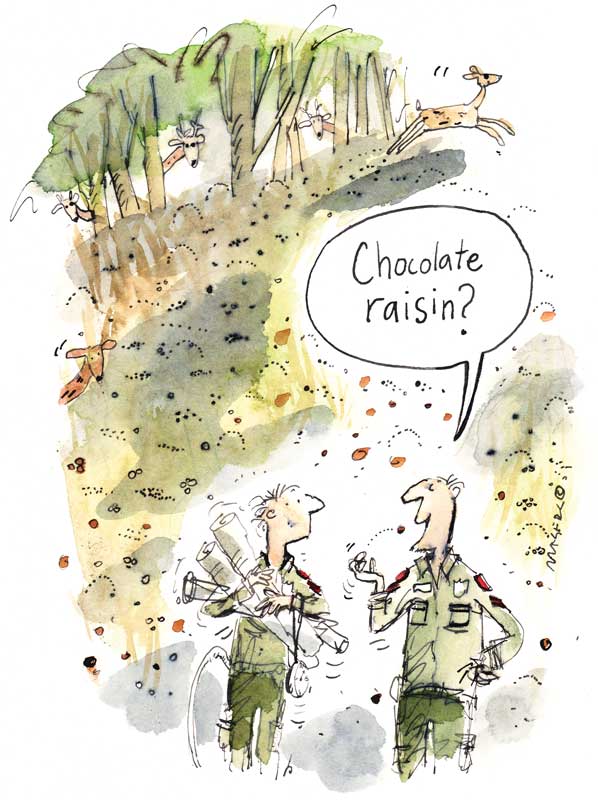

I followed Dumont into an urban forest near our Augusta office. Walking a deer path, he taught me to distinguish deer droppings from look-alikes produced by wild and domestic herbivores. Pointing to small cylindrical objects, he muttered, “Fresh deer dung. Note that each one glistens like a dark brown polished bead.” Minutes later, he leaned forward, examined additional small brown spheres, picked up a dozen and placed some in my palm. “These look like deer droppings,” he said, “but they’re not.” He tossed several into his mouth, leaving me speechless. “These,” he said with a straight face, “are chocolate-covered raisins. Don’t assume each pellet group is from a deer. Rabbit, sheep, and goat droppings are similar in shape and size.” (Dumont had planted the raisins 20 minutes before my training exercise.)

My work entailed walking transects in central Maine’s woods and fields. It was oddly reassuring to know that other state biologists from Kittery to Fort Kent were also stumbling over stumps and stepping in mud holes collecting deer dung data. If rural residents inquired about my field work, Dumont instructed me to reply, “wildlife surveys.”

My work entailed walking transects in central Maine’s woods and fields. It was oddly reassuring to know that other state biologists from Kittery to Fort Kent were also stumbling over stumps and stepping in mud holes collecting deer dung data. If rural residents inquired about my field work, Dumont instructed me to reply, “wildlife surveys.”

I once erred by telling a sheep farmer that I was counting deer poop. Eyebrows raised, she said, “Well I’ll be damned. So that’s what you’re doing with a college degree.”

An hour after signing my employment papers, I followed Dumont’s truck in my own from Augusta to Jefferson. I parked at the end of my mile-long transect and then rode with Dumont to the survey’s beginning point. Outfitted with a department uniform, L.L. Bean boots, clipboard, data sheets, Silva compass, and topographical maps, I began walking the randomly selected compass bearing route penciled on my map. Dumont’s transect paralleled mine by 2,000 feet. Protocol called for dropping a four-foot diameter hula-hoop-like object every 100 feet and recording the number of deer droppings inside the hoop. If I didn’t screw up, there ought to be 52 hula-hoop drops (survey plots) per transect.

As a biologist beginning a career on my birthday—a gloriously warm spring day to boot—I was thrilled to be part of a prestigious scientific team. I would soon learn, though, that wildlife fieldwork is fraught with unforeseen challenges.

Halfway through the transect, I discovered that my map of Jefferson was astonishingly outdated. Dated from 1958, many of the map’s green shaded areas—indicating forests—had been cleared during the previous 20 years. I jotted down land-use changes on the map’s margin and pressed forward, strictly adhering to my compass bearing.

Halfway through the transect, I discovered that my map of Jefferson was astonishingly outdated. Dated from 1958, many of the map’s green shaded areas—indicating forests—had been cleared during the previous 20 years. I jotted down land-use changes on the map’s margin and pressed forward, strictly adhering to my compass bearing.

Near the end of the transect, a house appeared in a clearing within the map’s green shaded area. I could also hear music. Minutes later, the sight of a nude young woman, about my age, floored me. She was sunbathing on the lawn, radio by her side, directly in line with my compass bearing. Head swimming and barely able to breathe, I retraced my steps 100 feet or so. Hiding behind a large oak, I pondered my predicament and Dumont’s final words of instruction: “Remember, don’t deviate from the compass bearing or it’ll throw a monkey wrench in the statistical analysis.”

Paul McCartney’s lyrics emanated from the radio: “With a little luck we can make this whole damn thing work out.” The words rang hollow: I’d need more than luck to escape this conundrum.

Should I veer off course several hundred feet and fail my first assignment or should I tiptoe past, hopeful that she wouldn’t hear me above the music?

I hastily alerted the woman by hollering to Dumont, who was hidden by dense forest somewhere east of me. The strategy worked. The woman scrambled to her feet and bolted into her home.

Heart pounding, I emerged from the woods, stared at my compass and walked past matted grass, a blaring radio, and a rumpled JAWS poster beach towel. The shark’s angry eye stared at me. In my peripheral vision I felt the woman’s eyes boring into me from a second-floor window.

Cresting a grassy knoll, I felt momentary relief at the sight of my parked Chevy. The flashing blue lights of a sheriff’s vehicle, though, signaled trouble. Dumont, the only person who could vouch for our fieldwork, was nowhere in sight.

Cresting a grassy knoll, I felt momentary relief at the sight of my parked Chevy. The flashing blue lights of a sheriff’s vehicle, though, signaled trouble. Dumont, the only person who could vouch for our fieldwork, was nowhere in sight.

Aside from accidentally frightening a young woman, my first workday had been blissful: the air had been alive with songs of migrant birds and skunk cabbages were unfurling their bright green leaves. Facing the sheriff, though, ended all joy.

Approaching the lawman, I crawled under a barbed wire fence and said, “I can explain what happened.” He snarled, “I’m all ears. Start explaining.”

Pointing to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife patch on my uniform shirt, I blurted that my job involved counting deer feces. The sheriff was unmoved. I flipped through dozens of deer dung data sheets hoping to convince him that I was not a peeping Tom. He recorded my name, work address, and phone number. Hopping into his cruiser, he asked, “Is there anything else you’d like to say before I visit the woman?” I replied, “Yes, please give her my apologies. And please tell her that her home does not appear on my 20-year-old map.”

Collating and analyzing statewide deer survey data was the responsibility of Gerry Lavigne, Maine’s top deer biologist. In May, during a wildlife biologists’ conference in Bangor, Lavigne stood at a blackboard explaining how he used the deer dung data to calculate regional deer densities per square mile. His convoluted mathematical equation on the blackboard was slightly less complex than the formula for Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. The data revealed, he stated, that northern and western Maine support relatively few deer per square mile, owing to long, harsh winters. Deer in central, southern, and coastal Maine, he added, are more numerous due to milder, shorter winters.

Estimating deer populations, though, remains an inexact science.

Demonstrating humor on par with Dumont’s raisin prank, Lavigne had hung on a conference room wall a framed photo of himself consulting a Ouija board. The caption read: “Forecasting Maine’s white-tailed deer population trends.”

The humor did little to squelch a biologists’ revolt over future pellet-group surveys. An Augusta bureaucrat tried dampening the firestorm by recalling his unusual encounter with a landowner: “A bearded man was meditating cross-legged in a field, and when I walked past counting deer droppings, he never opened an eye or twitched a muscle.” Animus turned to laughter when a grizzled, veteran biologist interjected, “Here’s the best part of your story—the hippie had a better explanation for what he was doing than you did.” The highly unpopular deer dung surveys were canned, as was the sheriff’s investigation.

My career as a wildlife biologist began peculiarly and then for nearly 40 more years it grew refreshingly variable and immensely rewarding. My wildly unpredictable field work ranged from rescuing orphan bear cubs at Mount Kineo to banding eaglets on David Rockefeller’s Bartlett Island in Blue Hill Bay. I had a wonderful career.

Writer Ronald Joseph is a retired Maine wildlife biologist. He lives in central Maine.