All images courtesy Lost Art Press

In 2013, I never could have anticipated what I was about to see. Pulling into the driveway of the Jonathan Fisher House in Blue Hill, Maine, I hoped to learn about the unstudied furniture-making of the town’s revered patriarch. I walked through the house and saw all the furniture that had survived (most of which was attributed to his hand), arranged to examine the tools used to make the furniture (which were also made by Fisher by the way), and then was taken into the archives—boxes upon boxes of manuscripts, notebooks, and letters, plus 40 years’ worth of daily journal entries about everything the man did every single day. Then I was handed the keys. Literally.

In 2013, I never could have anticipated what I was about to see. Pulling into the driveway of the Jonathan Fisher House in Blue Hill, Maine, I hoped to learn about the unstudied furniture-making of the town’s revered patriarch. I walked through the house and saw all the furniture that had survived (most of which was attributed to his hand), arranged to examine the tools used to make the furniture (which were also made by Fisher by the way), and then was taken into the archives—boxes upon boxes of manuscripts, notebooks, and letters, plus 40 years’ worth of daily journal entries about everything the man did every single day. Then I was handed the keys. Literally.

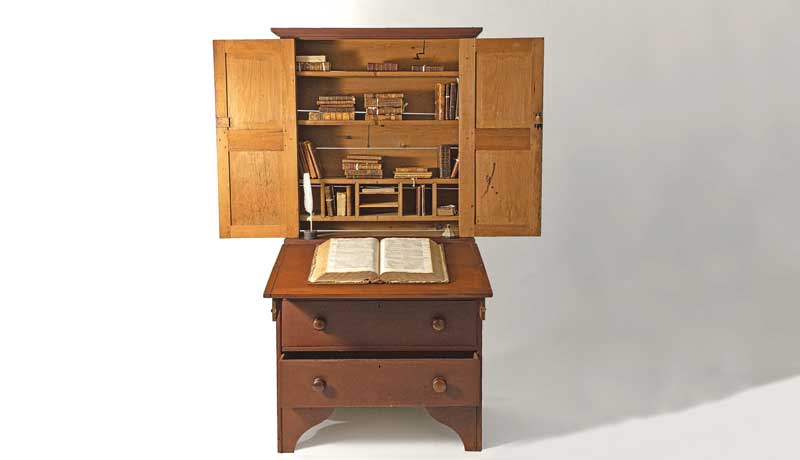

There were many moments in the research in which the author was struck by how foreign Fisher’s way of working was to modern woodworking. Seeing the insides of pieces like the drawer from this desk left surprisingly coarse caused him to reconsider the way he approached his own work. Jonathan Fisher Memorial’s former board president, Brad Emerson, told me the story of the astonishing survival of Fisher’s journal, objects, and narrative. I immediately got a photocopy of the transcribed journals and all available published research on Fisher and began to dig in. It was beyond my expectations. The journals described making his tools, setting up his lathe, and walking the commissioned pieces to his clients’ houses. This level of documentation and survival of artifacts was unprecedented because most pre-industrial cabinetmakers’ lives were undocumented in any detail. Fortunately for us, Fisher was an educated man who was taught the value of recording his life. Unlike many other craftsmen who were completely focused on putting bread on the table, he took the time to record the smallest details.

There were many moments in the research in which the author was struck by how foreign Fisher’s way of working was to modern woodworking. Seeing the insides of pieces like the drawer from this desk left surprisingly coarse caused him to reconsider the way he approached his own work. Jonathan Fisher Memorial’s former board president, Brad Emerson, told me the story of the astonishing survival of Fisher’s journal, objects, and narrative. I immediately got a photocopy of the transcribed journals and all available published research on Fisher and began to dig in. It was beyond my expectations. The journals described making his tools, setting up his lathe, and walking the commissioned pieces to his clients’ houses. This level of documentation and survival of artifacts was unprecedented because most pre-industrial cabinetmakers’ lives were undocumented in any detail. Fortunately for us, Fisher was an educated man who was taught the value of recording his life. Unlike many other craftsmen who were completely focused on putting bread on the table, he took the time to record the smallest details.

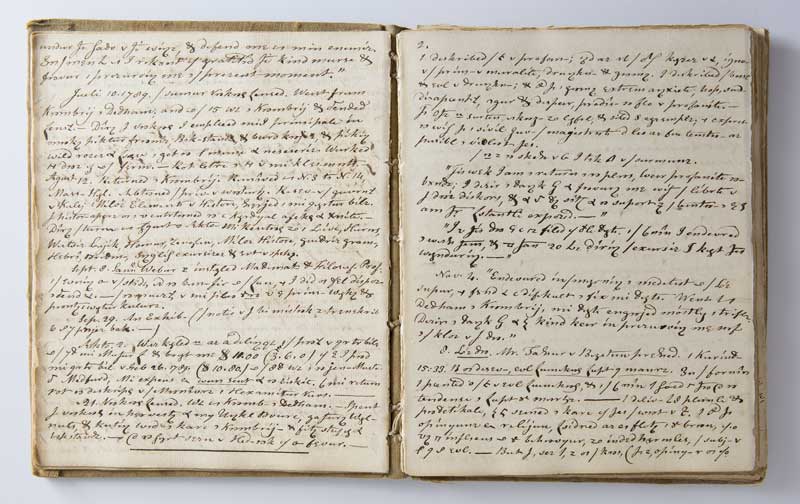

The story of Fisher is unique in its completeness. Because of his journal we know the answers to questions such as: What was going on in his mind as he built a piece? What was his life like that day? That week? What was his perspective on the pieces he made? Did he find satisfaction in working with his hands or was he dying to get out of the trade to enjoy a gentlemen’s leisure? When it comes to the lives of pre-industrial craftsmen, we almost never have answers to those questions. In the case of Fisher, however, we are deluged with so much information that it would take a lifetime to work through the archives.

In this self-portrait painted by Jonathan Fisher in 1824, Fisher represents himself as the learned minister in his study pointing at the Hebrew Bible. Collection of Blue Hill Congregational ChurchFisher (1768-1847) was the first settled minister in the frontier town of Blue Hill, Maine. Born in New Braintree, Massachusetts, he studied at Harvard College to prepare for a lifetime of faithful service to the Congregational church. Fisher has been described as a Renaissance man, a rural Jeffersonian polymath. He was at once a minister, scientist, artist, architect, linguist, historian, inventor, poet, farmer, and craftsman. What this man accomplished was absolutely incredible. He left behind an immense body of work that reveals not only his level of productivity but also his personality and artistic vision.

In this self-portrait painted by Jonathan Fisher in 1824, Fisher represents himself as the learned minister in his study pointing at the Hebrew Bible. Collection of Blue Hill Congregational ChurchFisher (1768-1847) was the first settled minister in the frontier town of Blue Hill, Maine. Born in New Braintree, Massachusetts, he studied at Harvard College to prepare for a lifetime of faithful service to the Congregational church. Fisher has been described as a Renaissance man, a rural Jeffersonian polymath. He was at once a minister, scientist, artist, architect, linguist, historian, inventor, poet, farmer, and craftsman. What this man accomplished was absolutely incredible. He left behind an immense body of work that reveals not only his level of productivity but also his personality and artistic vision.

During my time with Fisher’s records, I’ve become so familiar with him that he has almost become a mentor to me. I saw how well he dealt with failures, and how he interacted with his community with integrity. Like every good mentor, his peculiarities and pungencies forced me to reassess my own ways of viewing my work and life. (How could someone meticulously grain paint the front panels and yet leave the backboards rough-sawn from the mill?)

Fisher’s views of the world clash with many of our own. His approach to furniture making violates modern woodworking dogma. Despite the fact that I have fallen in love with Fisher’s work, it is important to be up-front about the fact that his work will not impress prestigious connoisseurs. Fisher did not build ostentatious masterpieces for the urban elite. Instead, his calling was to provide simple furniture made of local woods for his conservative, budget-conscious clientele.

He was transparent about his mistakes, too. On Dec. 30, 1814, he wrote, “Painted a little upon Dec. Stevens’ sleigh. Worked the rest of the day on picture frame plane stock. Stuck a chisel in the thumb of my left hand.” In March of 1805, after having done the task many times before, he wrote, “Worked upon a chair; broke it putting it together. Began another.”

It’s Fisher’s honesty that makes this story so compelling. What woodworker can’t relate to an unsuccessful assembly or to workshop injuries? These everyday journal entries provide the context to understand Fisher’s work; they allow us to step into his world to see what life was like for a 19th-century furniture maker on the eastern frontier.

Some woodworkers I’ve met (but not all) think history is boring and irrelevant. They want to create unfettered by tradition. What they lose in their isolation, however, is the mooring that gives our work meaning. When there is no effort to help the reader see the impact the lives of our ancestors should have on us, there is considerable loss. History is not an end in itself. It is an interpretation of the past that enables us to remember who we are and where we came from. We should be better for having read it.

It took several years of close examination to document and comprehend the body of furniture Fisher made. Various kinds of lighting from many different angles helped to discern the construction.

It took several years of close examination to document and comprehend the body of furniture Fisher made. Various kinds of lighting from many different angles helped to discern the construction.

As I’ve spent countless hours on my back under tables with a flashlight, examining tool marks and construction, I feel like I’ve gotten to know Fisher in a way that I probably wouldn’t have even if I met him in person. Examining the minutia of tool marks shows much about the maker’s mindset. It is like the way the brush strokes of master painters reveal their philosophy, culture, and even their personal idiosyncrasies.

Curator of prints at New York Public Library, Karl Kupp, described Fisher’s engraving skill this way, “Fisher’s style of engraving, in the manner of the typical primitive, shows the lack of training. But it is made up by a most fervent desire to please, and by an almost childlike persistence to get that animal upon the wood block, come what may.”

“His modeling is poor, that we must admit,” he wrote; “his proportions of drawing are not always right. But in the handling of the tool ... Fisher shows real feeling for the wood block and real craftsmanship in the execution of his engraving. He knows no fear in flicking out small bits to get the texture of either fur or feathers.”

I have found the same kind of analysis is possible through examination of the tool marks in Fisher’s furniture. When dovetails appear regular, even though close measurement suggests they were cut without a template, we learn how picky he was for detail. On the other hand, from a macro perspective, the lack of opulent ornamentation and restrained sense of design testifies to his conservative and religious world view (although his artistic whimsy and playfulness emerges in the desk he made for his children). Even if unconsciously, Fisher left behind tool marks that function as permanent inscriptions of his multifaceted personality and values.

This level of scrutiny leaves a craftsman awkwardly exposed because it reveals many of the parson’s imperfections. Getting to know Fisher in this way is, at times, uncomfortably intimate. Were we to have met him in person, the formalities and social graces surely would have buffered us from getting the “warts and all” look at the man. (We all do this, do we not?) But when we look at the inside of some of the utilitarian furniture he made, it’s there that we see what he’s like when not for show.

The Fisher House archives are full of notebooks such as this one, which detail his daily activities in his own unique shorthand. Jonathan Fisher Memorial

The Fisher House archives are full of notebooks such as this one, which detail his daily activities in his own unique shorthand. Jonathan Fisher Memorial

Period cabinetwork (much like today) was focused on the presentation surfaces. The undersides were left coarse because the 18th- and early 19th-century American economy did not support further refinement of such irrelevant areas. Accordingly, market expectations were such that no one thought twice about tear-out or riving marks on the underside. And certainly, no maker ever thought these surfaces would be photographed and published broadly.

In period work, almost every step of the construction process can still be read on the “secondary” surfaces (the undersides and insides). To be able to know the order of assembly, the direction of planing and the radius of the curve of the cutting iron is all information that tells us about who this artisan was and what their world was like.

Fisher’s house, in Blue Hill, which is open seasonally for tours, is full of furniture and other objects made by the parson. Being able to see the furniture he made in its original context helps us understand how and why he made furniture.

Fisher’s house, in Blue Hill, which is open seasonally for tours, is full of furniture and other objects made by the parson. Being able to see the furniture he made in its original context helps us understand how and why he made furniture.

The danger of over-emphasizing these surfaces could leave the casual reader thinking poorly of Fisher’s craftsmanship. But quality of workmanship needs to be determined contextually. It’s not fair to compare Fisher’s work with today’s post-Industrial Revolution standards. The question we should be asking ourselves is, “How does Fisher’s work compare to that of other makers serving similar rural 19th century markets?” The answer is that Fisher’s work, as rough as it may be, was par for the course. This might be one of the most important things we can learn from Fisher. Allowing coarse secondary surfaces not only allows us to work efficiently, but it is an opportunity to leave behind our “fingerprints” in the tool textures.

To a craftsman, this is like opening their underwear drawer. Know that Fisher never intended these artifacts to be intimately known. Welcome to the strange yet familiar world of Jonathan Fisher.

Adapted and excerpted from Hands Employed Aright: The Furniture Making of Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847) by Joshua A. Klein, Lost Art Press, 2018.

Adapted and excerpted from Hands Employed Aright: The Furniture Making of Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847) by Joshua A. Klein, Lost Art Press, 2018.