All images courtesy Carl Little

“On the Estuary” by K. Ashdowne, Esquire, from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River

“On the Estuary” by K. Ashdowne, Esquire, from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River

Sometime during his senior year at Dartmouth College (1913-1914), my grandfather Lester Knox Little was recruited to work in the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. It was the start of the Pawtucket, Rhode Island, native’s 36-year career serving the Chinese Government. His duties would range from collecting maritime trade taxes and managing harbors and waterways, to weather reporting and supervising anti-smuggling operations—in short, policing the China coast and the Yangtze River.

During his tenure with the service, a pattern emerged: six years in China followed by a year stateside. He was stationed in a different coastal city each time: Shanghai, Amoy, Peking, Tientsin, Canton. In 1918 he met and married Elizabeth Freeman and started a family: my father, John Watson Little, born in 1919, followed by my Aunt Betty, Elizabeth Freeman Little, born in 1920. The family joined him in China in the early years; the children attended the Shanghai American School.

Over the years traveling the coast, Little came to appreciate the vessels that navigated the harbors and estuaries. In 1947, in his capacity as Inspector General, he authorized the publication of the two-volume work The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River: A Study in Chinese Nautical Research by G.R.G. Worcester, river inspector for the Chinese Maritime Customs Service.

In his preface, my grandfather noted the inevitable changes under way in the 1940s as steam and internal combustion engines “with their superior speed and economy” supplanted “the sail and the oar.” Yet even as motorized vessels multiplied, he wrote, “an immense tonnage of cargo, and uncounted thousands of passengers, are carried by the junks and sampans described in this book.”

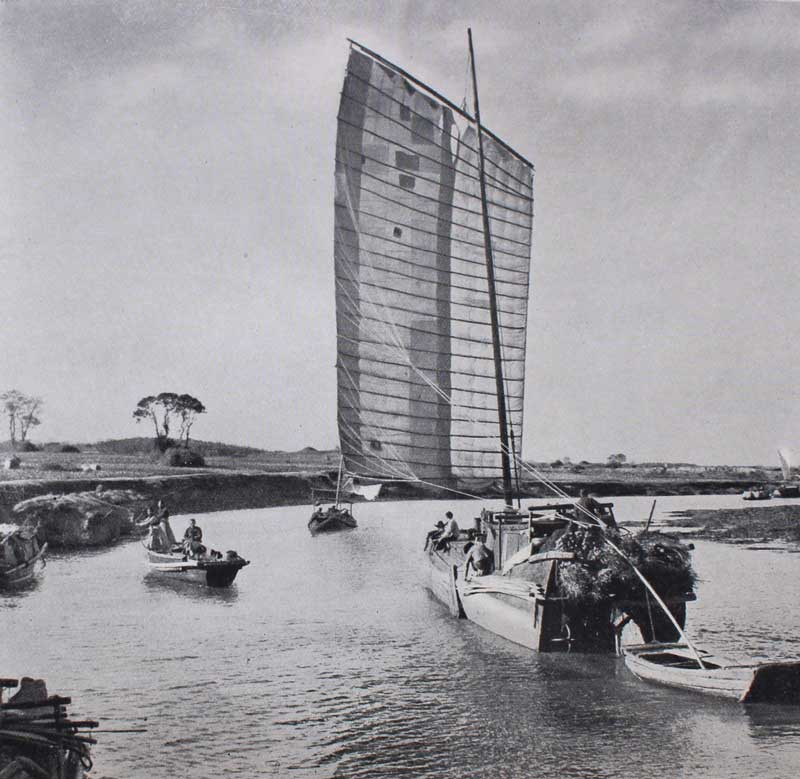

Leafing through the two volumes is to wonder at the remarkable variety of design of those vessels that plied the Yangtze, China’s most important inland waterway. Not all junks are alike, Worcester notes: “Nearly every waterside town and many a village has developed its own ideas of ornamentation and construction.”

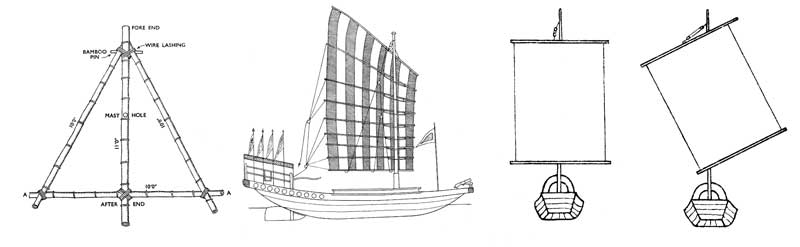

Illustrations from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River (top to bottom): design for bamboo buoy; river police boat; conversion of square sail into lug-sail. All images courtesy Carl Little

Illustrations from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River (top to bottom): design for bamboo buoy; river police boat; conversion of square sail into lug-sail. All images courtesy Carl Little

Junks generally feature fully battened sails with, traditionally, a horseshoe-shaped stern supporting a high poop deck. The Chinese, Worcester explains, “regard their junks as strictly neuter and, in the case of riverine craft, make no attempt to name them”—unlike the coast of Maine where even a dinghy carries a moniker.

Sampans are flat-bottomed, with a small attached shelter, and are usually propelled by poles or oars. The word is derived from the Chinese san, meaning three, and pan, meaning planks. Worcester pays tribute to the “genius” of the families for adapting themselves to the “most uncomfortable living conditions” aboard this humble craft.

Both types of vessels served all sorts of purposes: transportation and living quarters, fishing and ferrying. Worcester provides an extensive list of the cargo they carried up and down the rivers, including straw braid, joss sticks, rice, fans, silk, coal, manganese, timber, white wax, and herbs.

To combat piracy, Worcester reported, a “considerable force of sea-going war-junks patrolled the infested waters.” The Customs Service also employed police junks, called “fast crabs,” to chase craft that tried to avoid paying duties.

Worcester describes each craft with precise detail, from stem to stern, and includes sections on anchors, buoys, shipbuilding tools, and maintenance (“Junkbuilding or repair yards are usually situated up the smaller creeks”). In and among the maps, black-and-white photographs, and plans, he weaves local folklore and legends related to the boats.

Like Little, Worcester also remarks on the “invading power vessel” and grieves at the passing of the river boats. He describes a “tragic and splendid finale” when hundreds of them were filled with stones and sunk “to form the boom that barred the river to the invading Japanese at Matung in 1937.”

“On Inland Waters” by Mr. R. V. Dent, Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and Institute of British Photographers, from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River

“On Inland Waters” by Mr. R. V. Dent, Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society and Institute of British Photographers, from The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, my grandfather was Customs Commissioner at Canton. On December 8, 1941, he was placed under house arrest by the Japanese; the following year he returned to America aboard the Swedish ocean liner MS Gripsholm, which had been chartered by the U.S. Department of State as an exchange and repatriation ship during the war.

Little was eventually called back to China and was appointed Inspector General in 1943; at its peak, his staff consisted of 14,000 Chinese and 200 foreigners. On January 1, 1946, following the surrender of the Japanese, he reestablished the Inspectorate General at Shanghai. In October 1949, as the Communist armies swept southward, Little moved his office to Taiwan.

The Chinese government’s reliance on the Customs Service was demonstrated in 1948 when Little was instructed to transfer the national gold reserves to Taiwan. More than 80 tons of gold and 120 tons of silver were conveyed in small Customs ships even though large, well-armed naval vessels were available.

Resigning his post in 1950, Little was appointed advisor to the Minister of Finance and made annual visits to Taipei to confer on customs and other financial matters. He held this position till his retirement in 1954. Following his departure, the Inspector General position was filled by the Chinese for the first time in the nearly 100-year history of the service. Little was the last foreigner and only American to hold the position.

The citation for the honorary Doctor of Laws degree Dartmouth bestowed on my grandfather in 1950 highlights the esteem the Chinese Maritime Customs Service gained as “one of the unique wonders of the political world—a vast governmental operation in tax collection functioning efficiently and honestly, under advanced civil service principles.”

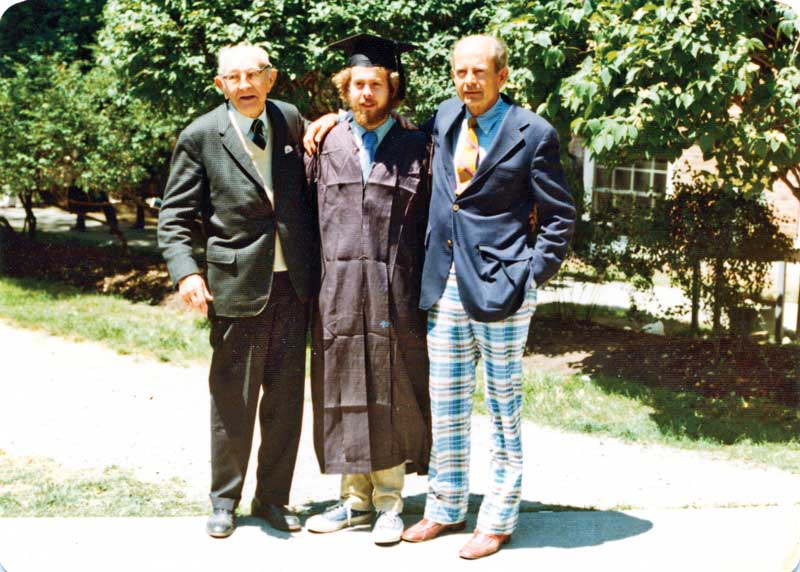

The author, center, at his Dartmouth College graduation, June 1976, with his grandfather, Lester Knox Little ’08, and his father Jack Little ’40. Note the clothing mix: business suit, un-ironed gown (with sneakers), and madras. Photo by Ruth Stoddard Little

The author, center, at his Dartmouth College graduation, June 1976, with his grandfather, Lester Knox Little ’08, and his father Jack Little ’40. Note the clothing mix: business suit, un-ironed gown (with sneakers), and madras. Photo by Ruth Stoddard Little

In 1963 my grandfather, known affectionately to my siblings and me as “Gompy,” moved with his wife Ruth from Washington, D.C., to Cornish, New Hampshire, near his alma mater, Dartmouth. As an undergraduate there, I visited him from time to time, often in the fall when my father came up for a football game.

I recall with enormous affection Gompy and Ruth welcoming their long-haired grandson into their lovely rambling house with its view of Mount Ascutney. The house was filled with artifacts from their lives in China (Ruth had her own fascinating life there before marrying my grandfather). Among the souvenirs on display was a check he had issued in 1948 for $120 million in Chinese dollars. He explained that during and after World War II, inflation became so serious that when the check in question was drawn, it was worth about $18.50. “I probably gave it to the cook to buy groceries,” he recalled.

When Gompy died in 1986, I was asked to say some words at his memorial service in Rollins Chapel at Dartmouth. I remember reciting part of a translation of Victor Hugo’s poem “Boaz Asleep,” a poem Gompy loved for its evocation of the love of Ruth and Boaz in the Bible. I also noted his oft-stated belief that the three courses essential to one’s education were Shakespeare, the Bible, and public speaking.

My copy of The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze River is inscribed to my parents, “For Jack and Patsy, with love from Dad, Shanghai, 1948.” Alongside my grandfather’s inscription is his Chinese seal, stamped in red. I treasure it.

Carl Little’s latest book is Philip Frey: Here and Now (Marshall Wilkes).