“Loomings” in Moby-Dick, by Rockwell Kent, who spent years of his life in Maine and illustrated the most influential edition of the novel in 1930. Courtesy of the Plattsburgh State Art Museum, SUNY Plattsburgh, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.

“Loomings” in Moby-Dick, by Rockwell Kent, who spent years of his life in Maine and illustrated the most influential edition of the novel in 1930. Courtesy of the Plattsburgh State Art Museum, SUNY Plattsburgh, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.

The writer Herman Melville’s 200th birthday was on August 1, 2019. As far as we know, he never dabbed a single toe in the state of Maine. The Moby Dick Hotel in Old Orchard Beach almost certainly does not stand anywhere near where the author of Moby-Dick once slept. He wrote a short poem about a troupe of Mainers who died in Louisiana during the Civil War, and some of his wife’s people lived in Bath and Hallowell, but that’s about as close to Maine soil as we can ascribe to the man, even if Melville surely looked over the rail into the waters of the Gulf of Maine during his three transatlantic voyages to Europe.

Yet despite so little biographical connection to Maine, the tentacles of Melville’s writing spiral and ooze around every harbor and pier on the coast today. Moby-Dick has become one of our elemental cultural stories about the ocean: a bottomless source for lessons, reinterpretations, artistic renditions, and off-color jokes. Most anyone can identify the major characters even if they’ve never read a word of the actual text. You don’t need an explanation for the white whale hooked throw pillow from L.L. Bean or the white whale dog collar from Two Salty Dogs. And go limping along the dock and see how long it takes until you hear an Ahab joke. In 2016, the Portland Museum of Art mounted an exhibition of illustrations around Rockwell Kent’s influential 1930 edition of the novel, and it drew over 13,000 visitors, including to a 24-hour marathon reading of Melville’s masterpiece. And this year, Colby College is running an exhibit of Alex Katz’s sparse illustrations of the novel from the late 1940s.

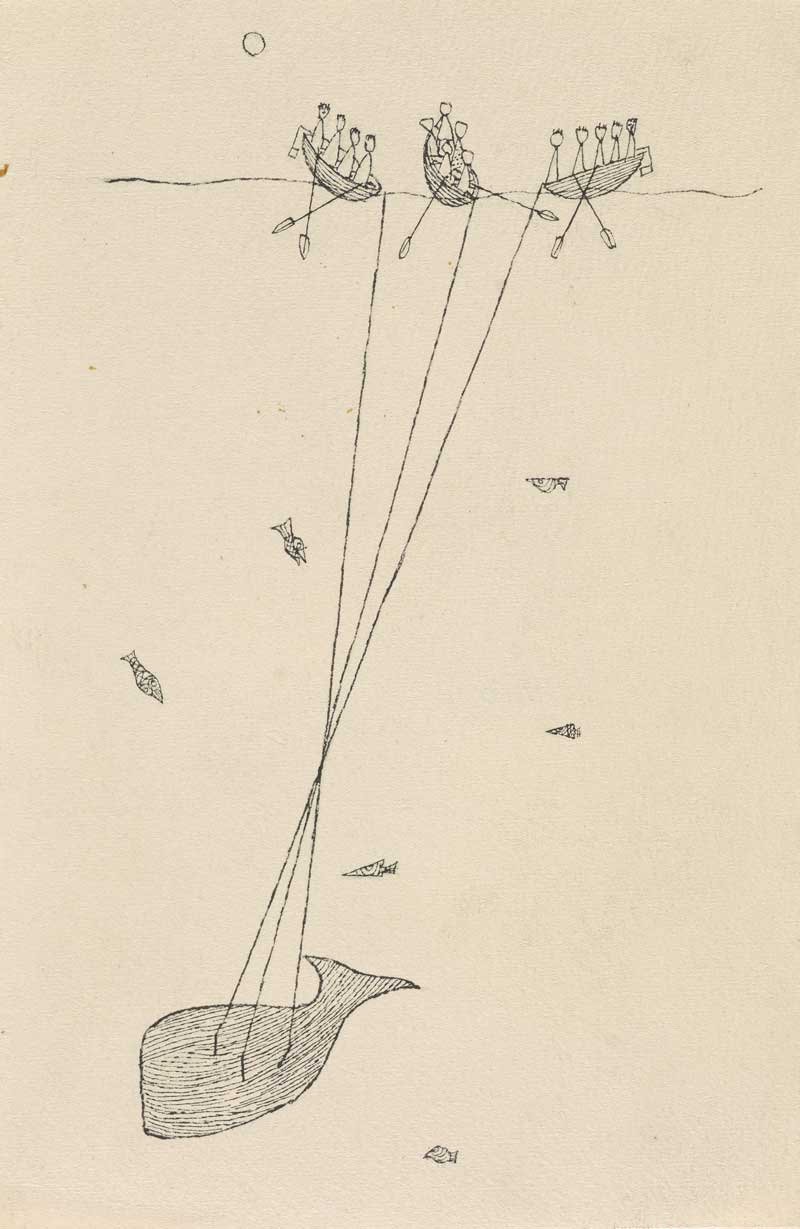

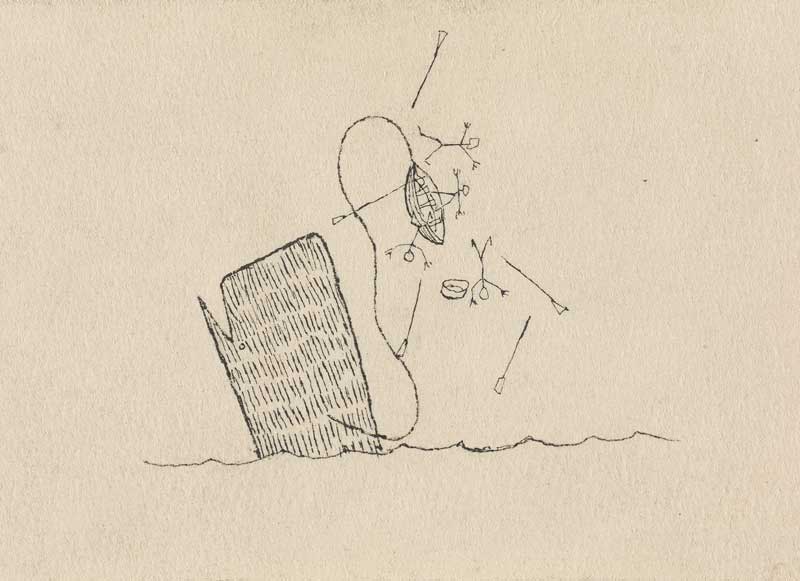

Fascinated by Moby-Dick, artist Alex Katz drew 27 illustrations as part of an art class in his student days. The drawings are on display through March 2020 at the Colby Museum of Art in Waterville. Top: Alex Katz, Untitled (Whale and Three Boats Above) 1948-49, Pen and ink on paper, 8x5 1/4 inches. Colby College Museum of Art. Gift of the artist. Bottom: Alex Katz, Untitled (Whale Knocking Boat in the Air), 1948-49. Pen and ink on paper, 31/8 x 5 1/4 inches. Colby College Museum of Art. Gift of the artist.

Fascinated by Moby-Dick, artist Alex Katz drew 27 illustrations as part of an art class in his student days. The drawings are on display through March 2020 at the Colby Museum of Art in Waterville. Top: Alex Katz, Untitled (Whale and Three Boats Above) 1948-49, Pen and ink on paper, 8x5 1/4 inches. Colby College Museum of Art. Gift of the artist. Bottom: Alex Katz, Untitled (Whale Knocking Boat in the Air), 1948-49. Pen and ink on paper, 31/8 x 5 1/4 inches. Colby College Museum of Art. Gift of the artist.

As we celebrate Melville’s 200th, Moby-Dick is especially useful as we grapple with climate change, because the novel is a benchmark for the way Americans used to connect with and perceive the ocean. His famous narrator, Ishmael, saw the sea in surprisingly similar ways as we do, although he could not foresee one enormous, nearly unimaginable perspective when his story was published in 1851.

Passengers in a 28-foot whaleboat from the Charles W. Morgan observe two humpback whales on Stellwagen Bank in 2014. Photo courtesy Ken Bracewell

Passengers in a 28-foot whaleboat from the Charles W. Morgan observe two humpback whales on Stellwagen Bank in 2014. Photo courtesy Ken Bracewell

The sea as a magical wonderworld

Melville first went to sea at the age of 19 in 1839 as a merchant sailor. After returning home and trying a variety of other careers, including cutting his hair and having a go at New York City office-work, he went back out to sea for nearly four more years, roughing his hands on three different whaleships and a U.S. man-of-war. I don’t think I’m exaggerating to suggest that the 19th-century whaleship provided a platform for the most careful observation of the deep-sea environment in the history of humankind, perhaps surpassed only by the knowledge of the early Polynesian navigators. Consider that Melville once spent six months without stopping at any inhabited port. Aside from a couple of anchorages in the Galápagos Islands, his captain tacked and gybed across the eastern equatorial Pacific, lollygagging around for whales as Melville and his shipmates took two-hour tricks each day up at the masthead searching the ocean’s surface.

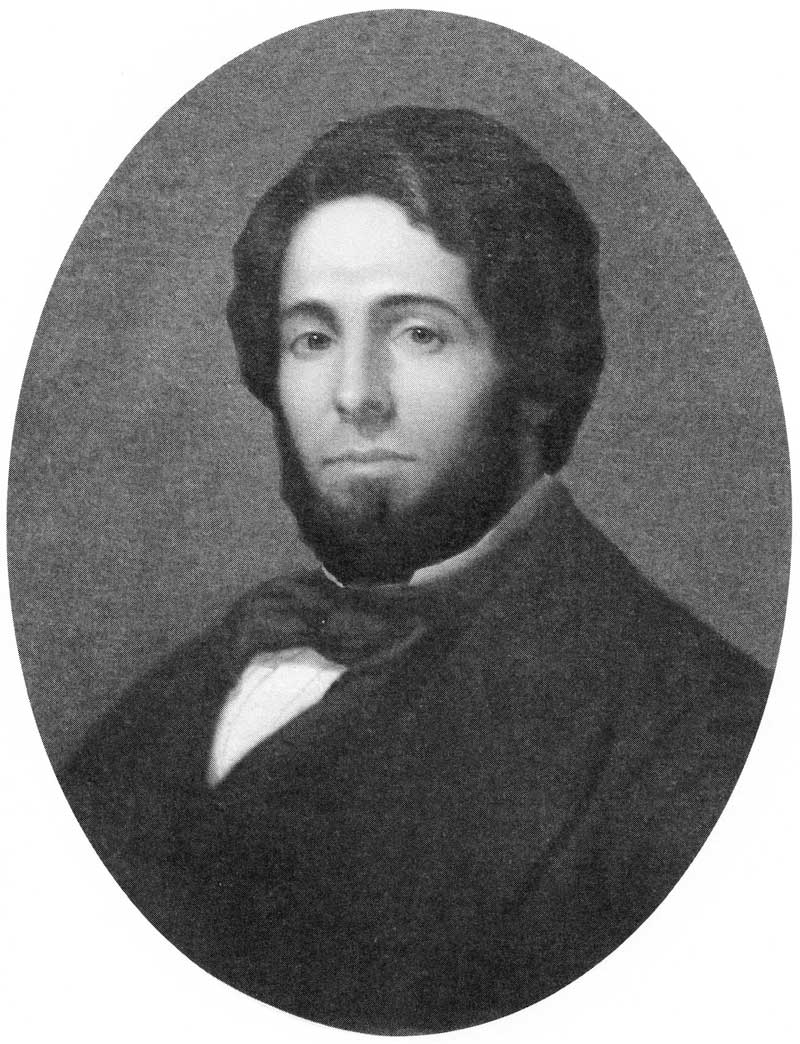

Herman Melville at about 28 years old, a couple years after returning from his voyages in the Pacific and before writing Moby-Dick.Out of sight of land, tens of thousands of 19th-century Americans, including Mainers, also spent hours upon hours in small boats: floating, engineless, waiting for whales to emerge. I’m not saying that whaleships were open scholarly platforms, or that every whaleman became a Charles Darwin or a Rachel Carson, but at no time before and I suspect never again, were so many young people sent out to sea to patiently watch deep ocean environments for such extended periods of time.

Herman Melville at about 28 years old, a couple years after returning from his voyages in the Pacific and before writing Moby-Dick.Out of sight of land, tens of thousands of 19th-century Americans, including Mainers, also spent hours upon hours in small boats: floating, engineless, waiting for whales to emerge. I’m not saying that whaleships were open scholarly platforms, or that every whaleman became a Charles Darwin or a Rachel Carson, but at no time before and I suspect never again, were so many young people sent out to sea to patiently watch deep ocean environments for such extended periods of time.

Whalemen had a hunters’ knowledge of the ocean. The closest we can get to this today is aboard the rare ocean cruiser that isn’t rushing from port to port, and aboard the science tall ships of the Sea Education Association (whose Corwith Cramer was refitted recently at Front Street Shipyard in Belfast). Yet even their voyages rarely last more than several weeks at a time.

In Mardi, one of his lesser known sea novels, Melville wrote: “I commend the student of Ichthyology to an open boat, and the ocean moors of the Pacific. As your craft glides along, what strange monsters float by. Elsewhere, was never seen their like. And nowhere are they found in the books of the naturalists.”

Melville represented the ocean as a place filled with wonderful organisms and spectacular weather events, as well as a place for spiritual nourishment. His saltwater horizon and contact with these wild organisms was healing and majestic and inspiring and thought-provoking. Sound familiar? Just read the first chapter in Moby-Dick, “Loomings,” and you’ll see he could just as easily be describing the 21st-century waterfront in Portland, Maine.

Who knows the sea best?

When I was trying to learn more about a scene in Moby-Dick where a swordfish stabs a hole in the hull of a whaleship, Maine fisherman and author Linda Greenlaw was kind enough to teach me about this fish’s behavior and the possibility of this sort of thing (it did happen). Greenlaw’s perspective on the sea and her own work as a fisherman is quite similar to that of Ishmael’s and the narrator of that passage in Mardi above: no one knows the ocean environment like the people working out there day after day. Melville read carefully the natural history texts of his time, but, like Greenlaw, he scoffed at any advice on marine biology from the “learned naturalists ashore,” people who had never seen or touched a living whale. In the 1850s, Ahab’s style of whaling was boom and bust, before coming under any government management. But Ishmael’s antagonism toward the broader scientific community of museums is similar to Greenlaw’s perspective on fisheries managers today, at least those whom she doesn’t believe spend enough time out there hauling nets or pots themselves.

Melville, like Greenlaw, was also quick to point out consumer hypocrisy. We might desire a given product from the sea, but lack the motivation to understand all the challenges of bringing it ashore. Melville would’ve appreciated how Greenlaw wants people to know the blood, sweat, and tears that go into the fish that you’re plopping on your grill. In 1816 Sir Walter Scott famously wrote: “It’s no fish ye’re buying—it’s men’s lives.” Melville toed that line in Moby-Dick and re-spun it for whale oil: “For God’s sake, be economical with your lamps and candles! Not a gallon you burn, but at least one drop of man’s blood was spilled for it.”

The sea as immortal, vast & violent

Melville’s ocean, especially in Moby-Dick, was immortal, vast, and violent. He declared this most directly in a little chapter titled “Brit,” which is the whaleman’s word for plankton—the collections of copepods, krill, and pteropods— that provide food for baleen whales. Ishmael begins “Brit” by describing right whales skim-feeding in the Indian Ocean, peacefully grazing amidst surface patches of plankton, and then he rolls into his own summation of an angry, predatory, endless sea: “However baby man may brag of his science and skill, and however much, in a flattering future, that science and skill may augment; yet for ever and for ever, to the crack of doom, the sea will insult and murder him, and pulverize the stateliest, stiffest frigate he can make.”

Melville published Moby-Dick just eight years before the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Melville was still heavily influenced by natural theology, weaving his experience on the water with his beliefs and struggles with Christianity. Ishmael and Ahab’s ocean is still God’s domain, and that sea will outlive humanity. At the end of Moby-Dick, despite all his wounds, we assume the White Whale lives—“only Ish and Fish survive,” as the Melville scholars like to say—and the closing words of the story are “then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago.”

As the Maine literary scholar Susan Beegel explains: “In Moby, it’s the sea that bats last.”

Saving the ocean

So Herman Melville saw the global ocean and mariners’ experience with this wildest of spaces in similar ways as we do today. What Melville could never have fathomed in the 1850s, however, was that humankind needs to be a steward of the coast: that we need to “save” the ocean and its creatures. His ocean was boundless and inexhaustible. He didn’t know how deep the oceans were at the time—the first deep-sea sounding apparatus was just being developed. Melville knew of local fish and marine mammal depletions, and he had read of the fossil records that revealed the reality of extinctions, but he did not believe, at least through Ishmael, that humans could do any lasting damage to life in the ocean.

For example, Ishmael knows that right whales (which he believed to be all one global species, including bowheads) had been eradicated from New England and over-hunted in other parts of the world. But in this time before diesel engines, stern ramps, and mounted explosive harpoons, Ishmael explains that these whales will always have their “Polar citadels” as safe havens from human hunting. In nearly all of his novels, Melville wrote of great plenty in the Pacific—fish, whales, squid, seabirds, brit. He believed the open ocean to be untouchable and beyond “the all-grasping western world.” That concept of an endless inexhaustible sea, passed down from Melville and so many other authors and artists, has been hard for us to shake.

If Melville were alive today, how might he have dealt with the fact that we have now proven that we’ve definitely impacted the ocean? We’ve altered its very chemistry, caused the rising of its seas, reduced—if not eradicated in places—the greatest, most pelagic populations of fish.

Melville might smirk that we still are watching that ocean come to get us, shuddering as it comes storming and seeping over our piers to have the last chance at bat.

Richard J. King is the author of Lobster, The Devil’s Cormorant, and the forthcoming Ahab’s Rolling Sea: A Natural History of Moby-Dick.