“Not only the days, but life itself lengthens in summer. I would spread abroad my arms and gather more of it to me, could I do so.”

—Richard Jeffries

English naturalist, 1848-1887

Dear Friends:

Illustration by Candice Hutchison As the summer season opens out before us, the first order of business is the celebration of Independence Day all over this vast country, right down to our small towns along the Maine coast. The flags, the parades, the family reunions, the cookouts all give this day its particular flavor. Public readings of the Declaration of Independence are customary in many places.

Illustration by Candice Hutchison As the summer season opens out before us, the first order of business is the celebration of Independence Day all over this vast country, right down to our small towns along the Maine coast. The flags, the parades, the family reunions, the cookouts all give this day its particular flavor. Public readings of the Declaration of Independence are customary in many places.

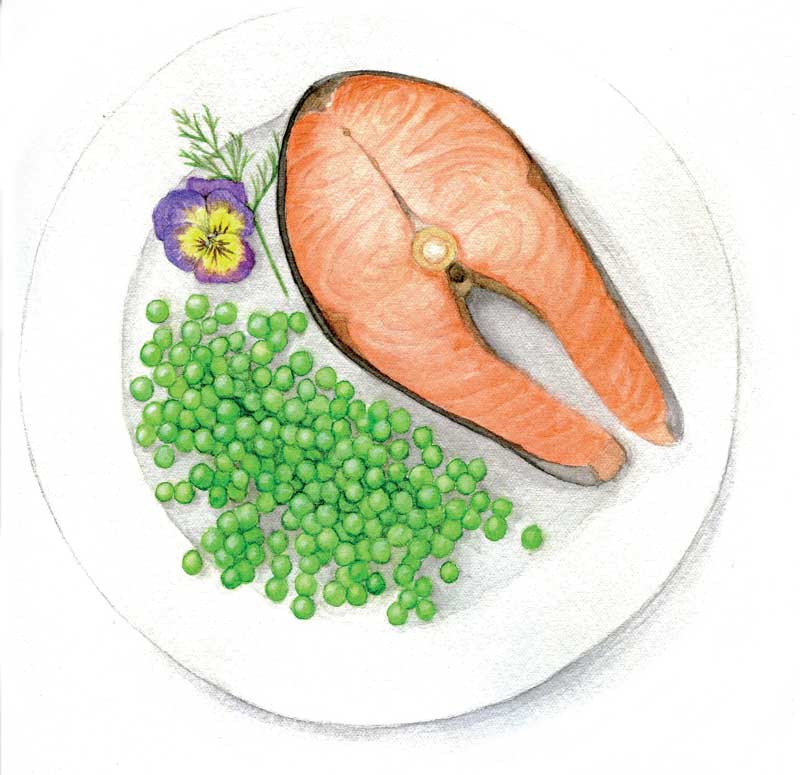

Maine’s traditional dinner on this day consists of salmon, peas, and—if nature cooperates—blueberry pie, though strawberry serves just fine.

Celebrating the Fourth of July brings us together for a time with family, friends, and neighbors to be thankful for our lives and our liberties.

Natural events, July

Summer is its own song and drama. The song of summer in Maine is in the notes of the hermit thrush echoing through the spruce and fir along the shore. Or in the white-throated sparrow’s “Old Sam Peabody.” Or it may be the lyrics of the loons calling to each other over the water. Maybe the song of summer is the wind in the white pines, the thunder rolling down off the mountain, the gronk of the great blue heron.

The drama of summer is in towering clouds watering the lush fields that overflow with wildflowers of intricate design, each bearing seeds of artful symmetry. Or it is the hatching of millions of eggs of every varied speckle and hue from millions of nests in tree and swamp and hollow. The drama of summer is the fuzzy, furry, or fledging young leaving the nest or den, some to live, some to die. It is the flaming sunrise over Campobello, lingering sunset over Penobscot Bay, and the ebb and flow of the tides. All these make up the drama and symphony of summer that play on the stage of these longest days.

Illustration by Candice HutchisonField and forest report

Illustration by Candice HutchisonField and forest report

Things are moving so fast as the parade of summer begins in earnest that it’s hard for your reporter to keep up. Yellow hawkweed gives way to the orange hawkweed or “Devil’s paintbrush,” while the buttercups are giving way to the daisies. The lupine goes by while the hauntingly beautiful wild iris, or blue flag, shines in damp sunny places. Seeds form on ashes and lindens, while oval cones with designs like ancient pottery form on conifers. Pink-tinted flower clusters form on valerian and petals fall from the lupine-like black locust. Also blooming is the common milkweed, Aesclepias

syriaca, which is essential to the life cycle of the iconic monarch butterfly.

We stand like spectators entranced by the most magnificent procession of all as the flora and fauna of the season day after day troop in succession before us: brilliant, beautiful, grim, gaudy, grand, aglow, and holy.

Rank opinion

Deep in our collective soul is an ancient awareness that we humans can affect the workings of nature for good or for ill, that our actions can help or harm our environment. We have that power, and we know it.

These days it’s knowing that heat waves, storms, droughts, and wildfires are getting worse because of human-caused global warming, but what to do? Remember a few years back when the monarch butterflies were disappearing and many pitched in to help? Thousands stopped blaming others and started planting milkweed. Forest habitat in the Southwest was set aside to conserve the wintering grounds of the iconic butterfly. Now every year we are see a few more monarchs coming back.

The monarch method can be applied to climate change just as well. Stop blaming present and past administrations, the oil lobby, Congress, or people driving big SUVs. Start using fewer fossil fuel ourselves, and show other people how good it feels. It’s as simple as that.

Saltwater report

Just below the surface, mackerel are flashing silver flanks to the sun. Mackerel fishers gather at the docks and breakwaters to cast their lines again and again. Gulls, terns, and cormorants throw back their heads as their catch slides down their throats. Sandpipers and yellow-legs strut along the shores, raising their feet as off a hot sidewalk, then fly off piping together in squadrons skimming over the waves. Sweet, hot, moist, wondrous summer.

Natural events, August

According to the venerable Old Farmer’s Almanac, the dog days of summer extend from the first week of July to the second week of August. Around here, they could often just as well be called the fog days. They are the hot and muggy days we endure in the interval between the sterling and crystal days of late spring and the buff and brown days of late summer, when clearer skies and cooler nights prevail.

The dog days were named in ancient times for the rising of Sirius, the Dog Star. Aristotle refers to them in his Physics and the Romans called them Caniculares Dies or the “days of the little dogs.” Even the Book of Common Prayer of 1552 declares that the “Dog Daies” begin July 6 and end August 17, but perhaps this is only for Anglicans.

Field and forest report

We learned last summer that a plant long thought to be extinct in Maine, unicorn root, or Aletris farinose—also called “colic root”—has been found minding its own business and growing contentedly in a field in Bowdoin. A member of the lily family, its leaves spring from a rhizome with small white flowers that grow at the top of a single stalk. Its medicinal uses include the treatment of colic, stomach ache, dysentery, and miscarriage.

It was recorded in The Flora of Maine, the monumental 14-volume work written and illustrated by Catherine Furbish (1834-1931), whose name will forever be connected to another rare plant, Furbish’s lousewort. Kate Furbish reported finding unicorn root in Brunswick in 1879, but it seems to have disappeared from Maine soon after that, until it showed up again in that field, perhaps wondering what all the excitement is about. How could it know that it was lost for over 130 years?

In the spirit of the rare unicorn root, here are some lesser-known blossoms and unsung flowers of the field—and the reasons they are worth noting. Maybe you have seen a single stalk up to six feet tall surrounded by soft, pale green fuzzy leaves and topped by a column of yellow flowers and growing in a sunny spot on rocky ground. This is common mullein, Verbascum thapsis, valued as a medicinal and thought to benefit the lungs when smoked or taken as a tea. The leaves are so soft and floppy and the whole plant so cartoonish it might have escaped from a children’s book.

Next is a little gem called eyebright, Euphrasia spp., a plant with trumpet-shaped white flowers tinted with purple, so tiny it is easy to trample underfoot. Eyebright thrives in snowy areas, like the south meadows below the summit of Awanadjo Mountain in Blue Hill. It is useful to treat allergies, and just happens to appear at the same time the heinous sneeze-monger, ragweed, is in bloom. Thank mother nature for that.

Last is pearly everlasting, Anaphalis margaritacea, also found on the south slopes of the mountain. It bears small white floral heads atop long stems lined with narrow fuzzy leaves that give the plant a dusty appearance. Everlasting is a member of the Aster family, related to daisies, sunflowers, and countless others. It was used by the First People as a medicinal and a tobacco substitute, and can be used in dried arrangements to last all winter—hence the name.

There you are: three often-overlooked wildflowers currently in bloom. Now, go on out and find them.

Rank opinion

Kate Furbish was hardly what you might call an environmental activist. She was a quiet, self-educated botanist who spent her entire long life wandering through the fields and woods of Maine, recording in beautiful water-color drawings the plants that she discovered. She never married or raised a family; the flowers of Maine were her family. And yet her discovery of a rare plant that grows only along the St. John River, running between Maine and New Brunswick, was instrumental in stopping the $900 million Army Corps of Engineers Dickey-Lincoln Dam project. It would have flooded forever 88,000 acres of wilderness along nearly 300 miles of that wild and beautiful river. Furbish’s lousewort, Pedicularis furbishiae, was the straw that broke the back of that boondoggle once and for all in 1985.

Never underestimate the power of tens of thousands of conservationists, hunters, and fishermen. And never underestimate the power of a lone, dedicated woman and a tiny, rare plant with a very odd name.

Seedpod to carry around with you

From Henry David Thoreau: “Who could believe in the prophecies… that the world would end this summer while one milkweed with faith matured its seeds?”

That’s the Almanack for this time. But don’t take it from us—we’re no experts. Go out and see for yourself.

Yr. mst. humble & obd’nt servant,

Rob McCall.

Rob McCall splits his time between way downeast on Moose Island and Brooklin, Maine. This almanack is excerpted from his weekly radio show, which can be heard on WERU FM (89.9 in Blue Hill, 99.9 in Bangor) and streamed live via www.weru.org. Tell Rob what you went out and saw for yourself at awanadjoalmanack@gmail.com.