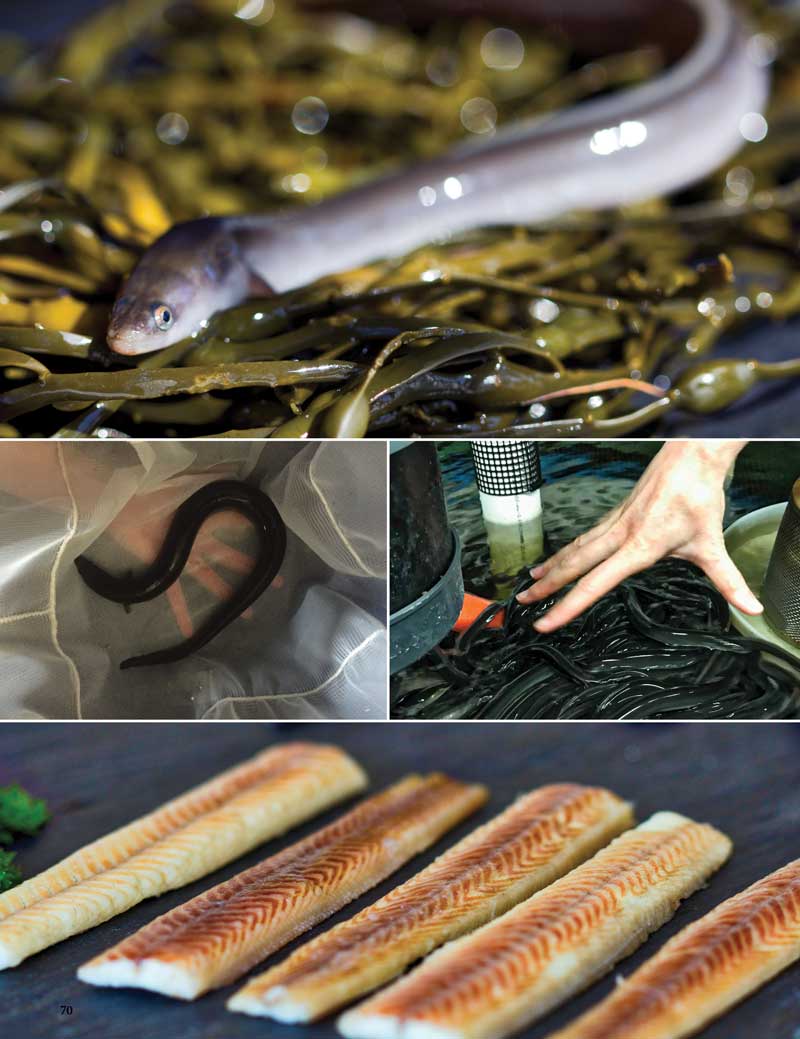

Top: It takes about two years for an eel to grow to market size. Photo by Jacinda Martinez Middle left: A mature eel can be as long as two to three feet. Photo by Sara Rademaker Middle right: Eels in a tank at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins Bottom: Eel fillets ready to eat. Photo by Jacinda Martinez

Top: It takes about two years for an eel to grow to market size. Photo by Jacinda Martinez Middle left: A mature eel can be as long as two to three feet. Photo by Sara Rademaker Middle right: Eels in a tank at the University of Maine’s Center for Cooperative Aquaculture Research in Franklin. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins Bottom: Eel fillets ready to eat. Photo by Jacinda Martinez

I moved back to Maine in the early 1990s, after many decades away, and took up residence in a small house overlooking Camden’s waterfront. From my back porch I could see across to the town with its church steeples, mill stack, and the picturesque waterfall where the Megunticook River somersaults over rocky ledges and tumbles into the harbor. One night in March of my first winter back, I was headed to bed when out a back window I saw a series of lights moving mysteriously around the waterfall. I watched on that dark and moonless night and speculated that this might have been a rescue operation for someone who had fallen into the water. Either that, I said to myself, or a drug bust.

As it turned out it was neither of those. The next morning I learned that what I had seen was the seasonal eel fishery in action. Fishermen use funnel-shaped traps called fyke nets to trap baby eels—also referred to as glass eels or elvers—as they make their way at night and on a rising tide, up over the falls. Those elvers that escaped the nets were headed past a half dozen old but still-functioning dams to Megunticook Lake. There, in the lake’s deep waters they would flourish and grow to maturity.

Eels are odd creatures. Unlike the many anadromous fish in Maine rivers (including salmon, shad, and alewives) that are born in fresh water, mature at sea, and return to rivers to spawn, eels are catadromous, that is the reverse. They spawn at sea and mature in fresh water. But that’s not all. All North American and European eels are born in the Sargasso Sea, a 700-mile wide subtropical gyre in the North Atlantic east of Bermuda. But they are elusive: No one, I am told on reliable authority, has ever seen a spawning adult, though not from lack of trying. The young eels, extremely small and nearly transparent, leave the Sargasso and head across the broad span of the Atlantic, looking for an estuary where they can make their way to a body of brackish or fresh water, where they develop and mature into full grown eels over 10, 20, even as much as 30 years. And then they go back to sea, homing in on the distant Sargasso, there to spawn and die.

Back to those fishermen in the middle of a cold March night, hip deep in falling water, harvesting baby eels. They were there because market demand for eels in Asia, especially in Japan, is overwhelming. In 1994, the year I first saw them in Camden, elvers were bringing $55 a pound and Maine fishers harvested a total of 7,347 pounds. Since then the price has climbed steadily, reaching $2,366 in 2018. That, I emphasize, is the price per pound. That was after the European Union had banned the export of eels, after the 2011 tsunami destroyed enormous quantities of eel aquaculture facilities in Japan, and after Asian eels were declared endangered in 2014.

The most recent statistics, for 2018, are a harvest in Maine of 9,191 pounds, with a total value of just over $21.7 million, making elvers Maine’s second most valuable harvest after lobster. Elvers are also harvested in South Carolina, but Maine is the major source of these tiny creatures, which are shipped to China or Japan to be grown out into full-fledged adult eels. Then they are transformed into a delicacy known as unagi no kabayaki, grilled eel that is roasted in a sweetly tangy marinade of soy sauce, sugar, and mirin (rice wine). It’s a hugely popular dish in Japan, where 100,000 tons of unagi are consumed annually—about 70 percent of the total world catch. If you’re a fan of Japanese food, you’ve probably had that kind of unagi tucked into a sushi roll or topping a nigiri mound. Almost all the unagi no kabayaki that we consume in American sushi restaurants, including carry-out sushi bars in supermarkets like Hannaford and Whole Foods, is imported as a ready-made product—that’s over 11 million pounds of eel annually. Ironically, more likely than not, much of that unagi started its commercial life as an elver caught in a Maine spring freshet.

It doesn’t take a mathematician to figure there’s a tidy bundle of cash to be made in what is the lean off-season for most Maine fishermen. And it doesn’t take a mathematician to calculate the carbon footprint of a fish that may be transported three or more times over vast distances before it reaches your local sushi restaurant.

Enter Sara Rademaker, a young, smart fisheries expert who got her early training in aquaculture at the University of Alabama, and then spent time in Uganda and Ghana helping to develop catfish and tilapia farms. She ended up at the Herring Gut Learning Center in Port Clyde where aquaculture and marine science are part of the organization’s mission.

“In 2012,” she explained, “the price of eels skyrocketed. And I said to myself, why are we sending all these baby eels abroad? Why aren’t we growing them out ourselves?”

If eels can be grown to market size in Asia, why not in Maine?

“And then,” she said, “I did a lot of back-of-the-envelope stuff, leg work, trying to figure out why no one has done this. Could it be sustainable?”

The only way to be certain was to try.

“I’d never grown an eel before,” Rademaker went on. “But in the spring of 2014, the state approved a permit that allowed me to acquire 100 glass eels from a buyer.” She put them in tanks in her Thomaston basement. “I wasn’t reinventing the wheel,” she added. “Eels have been farmed in Asia and Europe for decades.”

The University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, which supports and encourages aquaculture entrepreneurs, was her next stop, as she expanded her infant enterprise. I caught up with her there in the summer of 2018 as she was getting ready to move to a larger University of Maine facility in Franklin up a long inlet off Frenchman Bay, where she could raise 60,000 eels from elvers to market size, a process that takes up to two years. In 2020, she will be installed in her company’s own commercial facility in Waldoboro with good access to fresh water, a necessity for the land-based system she will use. “Land-based,” she said, “that’s the way the industry is going.”

Her Recirculating Aquaculture System, or RAS, is a long-established method of aquaculture that offers the advantage of being entirely self-enclosed, which means cleaner water in and out, resulting in healthier fish. It also means she can raise her eels without hormones or antibiotics, an important selling point. I asked her what else the process involves. “Love,” she said with a broad grin, “lots of love.”

Sara Rademaker hopes her American Unagi will put Maine eels on the nation’s plates. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Sara Rademaker hopes her American Unagi will put Maine eels on the nation’s plates. Photo by Nancy Harmon Jenkins

Right now, Rademaker sells her eels primarily to restaurants, either as fresh or smoked eel. Eventually she plans to reach a wider market, perhaps even introducing a Maine-made unagi no kabayaki.

Mainers are not great lovers of eels. My editor, when I pitched this story, was a bit squeamish before reluctantly agreeing to publish. And yet—eels are delicious. Old-time Mainers remember when they were harvested in late winter to early spring when there was not much else in the larder and the fat fish was a welcome and nourishing treat.

I sampled some of Rademaker’s American Unagi at Nina June Restaurant in Rockport. (Disclosure: Nina June is owned by my daughter, Chef Sara Jenkins.) The skin of the eel had been removed to expose fillets, which were easy to lift off the spine bones. Bathed in a kabayaki mixture of soy sauce and mirin, then grilled, they were unctuous and delicious. Not all eels get a Japanese treatment. At Sammy’s Deluxe in Rockland, chef Sam Richman smokes American unagi.

When it is simply roasted in its tough skin, the eel gains flavor from the fat that bathes the meat, after which the skin is easy to remove.

Italians—Romans, at least—traditionally eat eels on Christmas Eve although they no longer are caught in the Tiber; and Spanish eat the little transparent glass eels fried with garlic and chili peppers in very hot oil—so hot you’re given a tiny wooden fork with which to spear the eels. Anything metal, they say, would burn your mouth.

Will Rademaker really be able to reach her goal of selling more than 500,000 pounds of eel a year? It’s not as out-of-sight as it seems at first glance—that’s less than five percent of what we Americans currently import annually. Locally raised eels have a much lower carbon footprint. In addition, Maine-made and locally grown are valuable brands with class and quality. Rademaker’s project is clearly a step in exactly the right direction.

Nancy Harmon Jenkins is the author of many books and contributes to many publications, including The Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post, and Saveur.

Broiled Eel Japanese Style

At Nina June Restaurant in Rockport, Chef Sara Jenkins serves Maine eels, kabayaki style, over warm jasmine rice with a garnish of pickled radishes and cilantro, and sesame seeds sprinkled on top.

First—the eels must be skinned, which is the only hard part of this otherwise easy dish. At Nina June, the eels are decapitated and then packed in salt for a day to make skinning easier. To remove the skin, tug back a corner of the skin at the head end, then, using pliers or work gloves, pull the skin back the full length of the fish. Once you get started this is easy, like pulling off a pair of opera gloves. Cut the eel into approximately 3-inch lengths.

Two one-pound eels should make four servings as an appetizer. Once the eels are prepared, continue with the recipe for the unagi sauce using the following ingredients:

- ¼ cup mirin (Japanese rice wine)

- 1½ tablespoons sake

- 4 tablespoons white miso paste

- 3 tablespoons maple syrup

Combine the mirin and sake in a small saucepan and bring to a simmer over low heat. Cook just long enough to throw off the alcohol, then whisk in the miso and stir to dissolve. Now turn the heat up to medium and add the syrup. Cook for 5 to 10 minutes, or until the sauce is thickened, then set aside to cool. (This step can be done well in advance.)

When you’re ready to cook the eels, set the broiler on high. Spread aluminum foil on a broiler pan and brush with a little oil. Add the eel pieces and brush each piece lightly with oil. Set under the broiler for about 5 to 7 minutes, then remove and brush with a good coating of the unagi sauce. Return to the broiler for another minute, until the sauce on the fish is bubbling and richly caramelized.

Remove and serve immediately as described above, or if you wish, set aside and serve later at room temperature.

Note: The unagi sauce can also be made in larger quantities; it keeps well in the fridge for several weeks or even months.