Photographs by David Webster Smith

As it approaches the container ship in the bay, the tugboat looks like a pit bull puppy chasing an eighteen-wheeler. When the vessels are an arm’s length apart, the ship’s mate throws down a line. Now leashed to the ship, the tug can push and pull it around. Big ships can’t easily slow down or maneuver by themselves—they’re meant for going in a straight line.

Tugboat crews routinely encounter what few of us will ever see. They easily read a vessel’s size, shape, function, and features, while deciphering at a glance the mysterious numbers, letters, and symbols on a ship’s hull. To non-mariners, the markings look like hieroglyphs. For those in the know, they speak volumes about a particular ship and also about the shipping industry.

Oceangoing vessels carry more than 80 percent of the world’s trade, with more than 90,000 merchant ships plying international waters. Tankers, bulk carriers, and container ships—the largest things on earth that move—convey billions of tons of goods every year, carrying everything from cars to crude oil to containers jammed with fidget spinners.

Those who work in ports or on the water have a good view of the proceedings; tugs may have the best view of all.

“The sides of ships have their own sort of beauty,” says photographer David Webster Smith, who is also a tugboat engineer. “As soon as I can, I get my camera out.”

This photo was taken from a tug that’s moving in on a tanker, guided by white arrows pointing to chocks that house small but strong posts called bitts. The tug fastens lines to these bitts.

SWL 50t means that the safe working load for each bitt is 50 tonnes. Once the tug has fastened a line to the bitt, it will exert no more than 50 tonnes of pulling pressure as it helps the ship brake or negotiate docking.

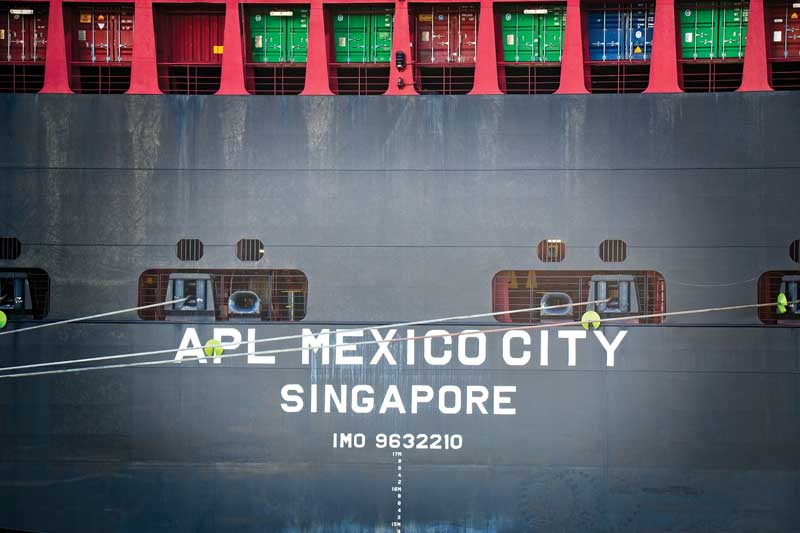

Most ships have clues to their identity emblazoned on their stern, often in the same order: owner, name, port (or “flag”), and International Maritime Organization (IMO) number. American President Lines (APL) owns this ship, christened the Mexico City, and it sails under the flag of Singapore.

The owner, name, and flag may change over a ship’s lifespan, but the IMO number stays the same as mandated by an international maritime treaty. Like vehicle identification numbers, IMOs help thwart fraud. Do a web search on an IMO number and the ship’s full history pops up.

Curious about those yellow-green, fortune-cookie-shaped objects along the lines? They’re anti-rat devices, foiling rodent attempts to scrabble from dock to line to ship.

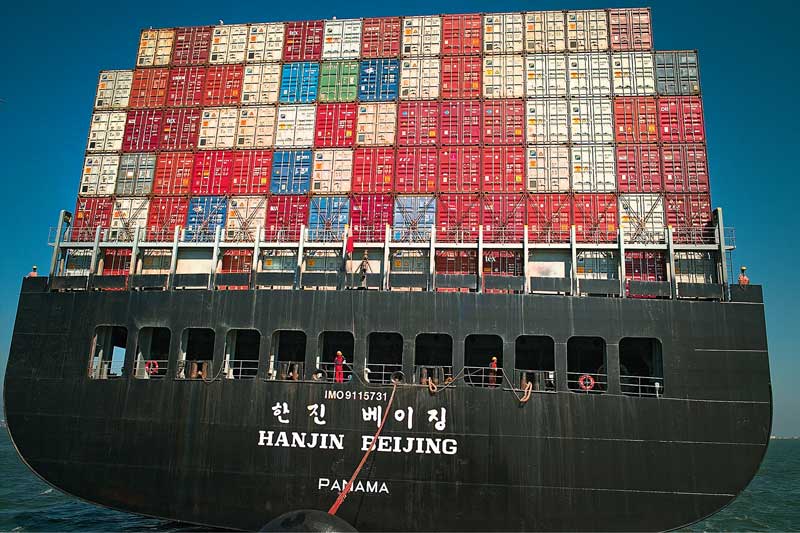

Why would a ship owned by a South Korean company (Hanjin) list its port as Panama?

More than 70 percent of the world’s commercial ships sail under what’s called a “flag of convenience.” This means that the ship is registered in a foreign country and sails under that country’s flag, usually to reduce operating costs, sidestep taxes, or avoid the stricter safety standards of the owner’s country.

By far the most popular flag of convenience is Panama, with Liberia and the Marshall Islands fast gaining ground. For these countries, the fees companies pay to fly their flags are a significant source of revenue.

There’s another thing about this ship worth mentioning. See the crew members up on deck, at the far left and right of the photo? They’re actually dummies dressed as mariners, meant to fool pirates into thinking someone is always on watch.

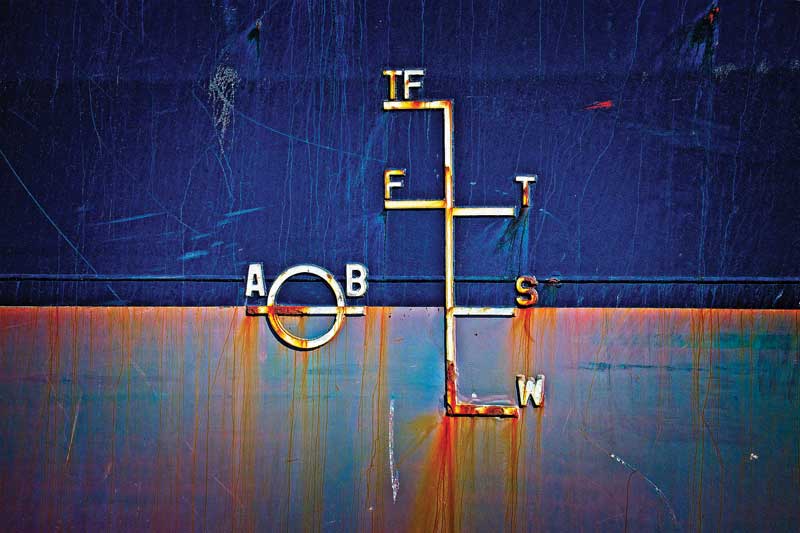

These marks, called load lines, show the maximum load a ship can carry.

Load lines owe much to a British member of Parliament named Samuel Plimsoll. Worried about the loss of ships and crew due to overloading, he sponsored a bill in 1876 that made it mandatory to have marks on both sides of a ship. If a ship is overloaded, the marks disappear underwater. The original “Plimsoll line” was a circle with a horizontal line through it. The symbol spread around the world; additional marks were added over the years.

The letters on either side of the circle stand for the ship’s registration authority. AB is the American Bureau of Shipping, one of 12 members of the International Association of Classification Societies, which sets and maintains safety standards for more than 90 percent of the world’s cargo ships.

The marks and letters to the right of the circle indicate maximum loads under different climatic conditions. Salt water is denser than fresh, cold water denser than warm. Since water density affects ship buoyancy, different conditions call for different load lines.

W marks the maximum load in winter temperate seawater, S in summer temperate seawater, T in tropical seawater, F in fresh water, and TF in tropical fresh water, like that of the Amazon River.

This ship is equipped with a bulbous bow. Contrary to its ungainly appearance, the bulb actually reduces drag, increasing speed and fuel efficiency.

The white symbol that looks like the numeral five without the top line alerts tugboats to the presence of the bulb, which under certain conditions may be entirely under water. Tugs need to be aware of the protuberance to avoid running it over as they maneuver around the ship.

The white circle with an X inside signals the presence of a bow thruster, a propulsion device that helps the boat maneuver sideways, a boon for getting on and off docks.

The numbers arranged in a vertical line—called draft marks—measure the distance between the bottom of the hull and the waterline. If the water comes up to the 11-meter line, for example, that means 11 meters of the ship are underwater.

Where the water hits the draft lines tells sailors if the ship is overloaded, and—when compared to the reading on the opposite side of the boat—if it’s listing to one side.

To the left of the draft lines are different versions of the bulbous bow and bow thruster symbols. BT|FP tells you the position of the bow thruster: between the ballast tank (BT) and the forepeak (FP), the forward-most part of the ship. It’s important for a tugboat operator to know the location of the bow thruster, as it creates turbulence that the tug would rather avoid.

Are these bird cubbies, rusting in the sea air? Not quite. The cavities are, however, known as pigeonholes. They’re part of an in-hull ladder that allows mariners to climb up the side of a barge.

Unlike cargo ships, flat-bottom barges are not self-propelled. They’re usually towed or pushed by tugboats, though in the early days they were hauled up rivers and canals by horses, mules, or donkeys on an adjacent towpath. Though barges are often unstaffed, they occasionally must be boarded, for instance when a line needs to be thrown down to a dock worker.

The white rectangle edged in yellow—a pilot boarding mark—tells the maritime pilot where to board the ship. Maritime pilots are experts on the navigational hazards of their home harbor and crucial characters in the drama of maritime life.

The pilot catches a ride out to the ship on a boat about the size of a tug, scrambles up a ladder hanging off the cliff-like side of the ship, and takes over for the captain as the ship comes into port. The rope ladder may not yet be deployed when the pilot boat approaches a ship, so the boarding mark is an important guide.

The white marks on the red are battle scars, reminders of scuffles with docks, other vessels (mostly tugs), and the sides of canals.

A maritime pilot would board this ship using the two ladders pictured. First, he or she would ascend the rope ladder, sometimes called a Jacob’s ladder, alluding to the biblical Jacob, who famously dreamed of a ladder connecting heaven and earth.

Partway up, the pilot would sidestep onto the relative security of the diagonal gangplank, called an accommodation ladder.

Sometimes the pilot makes do with just the rope ladder. According to IMO regulations, if the distance from water level to deck (which changes according to ship load and sea conditions) is more than nine meters, the ship must deploy an accommodation ladder in addition to the rope ladder. Nine meters or more is a long climb on a rope ladder, especially under difficult sea conditions.

Boarding and disembarking are probably the most dangerous parts of the job. To get off the ship, pilots may let go of the ladder and use what’s called a manrope to help them onto the deck of the pilot boat. Why? Well, that way they’re less likely to be crushed between the pilot boat and ship.

Erin Van Rheenen writes about science, travel, and the outdoors. David Webster Smith works on a tugboat in San Francisco Bay.

An earlier version of this story appeared online in Hakai Magazine.