Will Frost (standing) and son Bert Frost in Jonesport, Maine, next to one of their boats in the mid-1930s. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, Atlantic Fisherman collection

Will Frost (standing) and son Bert Frost in Jonesport, Maine, next to one of their boats in the mid-1930s. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum, Atlantic Fisherman collection

New England weathermen predicted a calm fall day for that Wednesday in late September. There had been a hurricane in the Atlantic, but it was believed to have gone out to sea. September 21 dawned bright and clear, but some felt uneasy. Cows milled about, and no birds were heard. A farmer in Vermont smelled salt water. As the day passed, the sky turned sickly yellow.

Known by some as the “Wind That Shook the World,” by others as the “The Yankee Clipper,” “The Long Island Express,” or “The Great New England Hurricane,” the hurricane of 1938 slammed into New England 80 years ago and left unimaginable destruction in its wake. Coinciding with a full moon autumn equinox and an incoming tide, the storm smashed past Long Island traveling 60 mph, then hit Connecticut and Rhode Island, and raged over the rest of New England, passing through western Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont before dying away in Quebec.

Winds of up to 200 mph were recorded in Long Island, and 121 mph near Boston with a peak gust of 186 mph. In Providence, Rhode Island, the storm wave was 100 feet high, breaking the skylight of the Providence Library; the streets flooded with 14 feet of water. It was one of the largest natural disasters in U.S. history, killing 700 people, injuring more than twice that many, and inflicting several billion dollars of damage in today’s currency.

President Roosevelt sent crews to help with cleanup, and the government bought fallen timber from landowners to assuage the losses. Much of that timber was used to outfit boats built for WWII. Nine years later, the Northern Kraft Paper Mill in Howland, Maine, was still using wood that had been cut from trees downed by the 1938 hurricane.

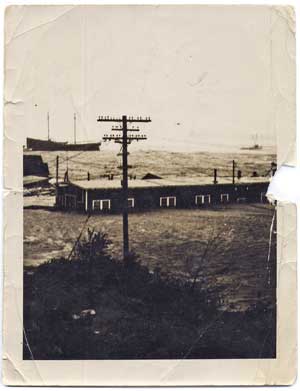

The Frost boatshop in Tiverton, Rhode Island, was surrounded by water during the hurricane of 1938, and later washed away. Photo courtesy Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, MaineEach community and each family had its own memories of that day. Chaos, devastation, and obliteration; houses relocated or destroyed; loved ones dead or disappeared; heroic rescues and odd happenstance. These amazing stories have filled many books and reports.

The Frost boatshop in Tiverton, Rhode Island, was surrounded by water during the hurricane of 1938, and later washed away. Photo courtesy Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, MaineEach community and each family had its own memories of that day. Chaos, devastation, and obliteration; houses relocated or destroyed; loved ones dead or disappeared; heroic rescues and odd happenstance. These amazing stories have filled many books and reports.

In September 1938, the boatbuilding Frost family was in the process of moving from Massachusetts to Rhode Island. The Depression had set them on the move from Jonesport, Maine, to Massachusetts several years earlier in search of more work. Most of the Frost men had found jobs with Baltzer-Jonesport Boat Company in Medford, Massachusetts, but boat owners were encouraging them to open their own shop again. They had located a building for lease on the Sakonnet River in Tiverton, Rhode Island.

On September 20, Will and Marcia Frost had moved to Tiverton. The morning of September 21, the day the hurricane struck, their son Bert Frost (age 29) had just arrived in town. Will Frost, 64, was down at the shop “getting everything shipshape,” his daughter Wilhelmina Lowell wrote much later in a short memoir about her father’s boatbuilding. “He had not noticed the increase of the gale, he was so interested in his work, until he heard water running. He looked around and saw the ocean pouring in the doors and windows!” Frost climbed a ladder up into the overhead beams. Fortunately, the waves receded before reaching him, and he was found later by rescuers in boats.

The next tide took the building with it.

“Such devastation I never witnessed in my life,” Bert Frost said in a narration he recorded shortly before his death in 1975. “We were helpless there in 125-mile-an-hour winds.”

“Boats, big ones, were going in all directions,” he recalled.

“So you just watched everything go. Just about high water the swirling mass was right out off of the dock where the boatshop was. Finally the shop lifted, went out in that brutal tide. The building hit a nearby railroad bridge and stove all to smithereens,” he said. “There was all of our machinery, and our carpenter's tools, everything all carried away in that building.”

Bert Frost’s daughter Harriet Vaughan has a wooden bowl her father made from a walnut tree that fell on their house during the storm. “I think of the bowl as a symbol for dealing with adversity,” Vaughan said. “When a tree destroys your roof, turn the darn thing into a bowl and use it!”

Soon after the hurricane, a local paper wrote an article about the new Frost shop. A caption stated, “William Frost... has built many boats, among them the Wahoo, owned by Edward Brayton of Fall River, which carried several Sakonnet Point fishermen to safety in the recent hurricane.”

Brayton was an avid sportfisherman. With John Alden, he founded the Sakonnet Yacht Club near where the east side of Narragansett Bay meets the Atlantic. That’s where he moored his swordfishing boat Wahoo, which was built by Will Frost in Maine in the 1930s.

A fisherman named Allen Kimpel commandeered the Wahoo during the storm. He was part of a group of fishermen called Grinnell’s Fishing Gang who bunked in a large Sakonnet Point building.

Downriver from Tiverton, Sakonnet Point consisted of a couple of dozen buildings perched on a spit at the edge of the ocean: cottages, tourist lodging houses, restaurants, and fishermen’s shanties. Ten fishermen were at Grinnell’s when a huge wave flung the building and its occupants into the raging water.

“We thought the end had come,” Kimpel told the Providence Journal afterwards, “but kept a weather eye open for something we could leap to. The Wahoo... loomed up and as the building was passing it, I jumped and caught on the mooring headfast.”

He was able to climb aboard with three others, and start the engine. “We had all we could do to stay in the boat and we were using both hands to hold on,” Kimpel said.

As the storm progressed, the mooring line broke, “but we were ready,” said Kimpel. “I gave it full speed ahead, and I don’t mean maybe. Boy, did we come in.” Observers said it looked like an airplane approaching.

Around a ledge, over submerged debris, they zoomed into the lee side of the Yacht Club wharf. The men climbed onto the dock, while Wahoo drifted past and was beached. “The boat saved the fishermen and in turn the fishermen saved the boat. It was one of few craft which survived the blow,” commented the Providence Journal.

Two of the others from Grinnell’s were washed to shore, one six miles upriver with only his shirt left. The remaining four were never seen again and presumed drowned. After the storm, Sakonnet Point was completely bare except for telephone poles and one or two large houses. Seven people lost their lives in the area, according to newspaper reports.

Beals Island fisherman Alfred Beal and Bert Frost have both commented that Will Frost’s old narrow boats might scare you to death, but they’d always bring you home safe. Thankfully, this proved true for Allen Kimpel and the others aboard the Wahoo.

“It’s a good thing it was a staunch craft or it never would have weathered the awful seas,” said Kimpel.

The Frosts were glad to hear of one of their boats being a small help during a tremendous tragedy.

Ruth Lowell has been researching nautical history for about 20 years. Her husband Jamie is one of Will Frost’s great-grandsons. Jamie and his brother Joseph operate Lowell Brothers boatshop in Yarmouth.