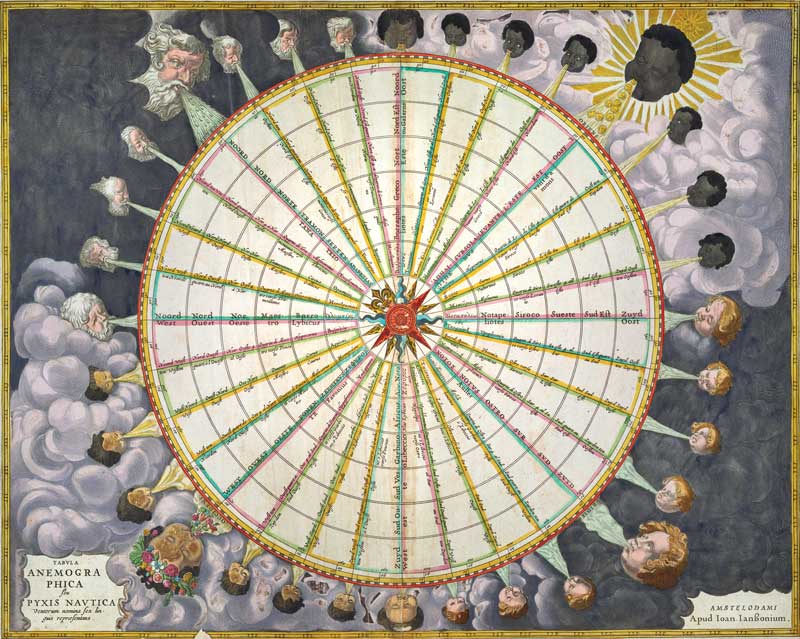

Over the centuries, an increased diversity of names for the winds and ambiguity about the direction they came from produced a multitude of different wind systems. To create order out of the tangled confusion of names and directions, cartographers produced wind roses such as this by Jan Jansson in 1650. Image From the Osher Map Library, Portland

Over the centuries, an increased diversity of names for the winds and ambiguity about the direction they came from produced a multitude of different wind systems. To create order out of the tangled confusion of names and directions, cartographers produced wind roses such as this by Jan Jansson in 1650. Image From the Osher Map Library, Portland

You can’t be a good sailor without possessing a peculiar sensitivity to the wind. Not the standard “gosh, it’s a bit breezy out” variety of awareness, but rather a deep-seated understanding of where the wind comes from and what it may be up to in the next minute, or hour, or day.

Sailors’ obsession with the wind can be traced to the ancient Greeks. Exquisite navigators, Greek sailors were able to traverse the Mediterranean far from the sight of land because they understood the link between wind directions and the seasons. At different times of the year they could rely on Notus, the warm south wind, Zephyr, the mild west wind, Boreas, the cold north wind, or Apeliotes, the dry east wind, to take them where they wanted to go.

Maine fishermen have long known where they stand in terms of the prevailing winds. After all, Maine juts out from the rest of New England in a distinctly easterly direction. In times past, vessels traveling from New York or Boston made use of the dominant southwesterly winds to make quick passage “downeast” to Portland and other Maine harbors.

But what are the sources of Maine’s winds? Where do they come from and how do they vary during the year?

To answer that question, one must remember that the earth is round. The great energy of the sun falls directly on the equator throughout the year, thus keeping the air above the equator hot year-round. The sun’s rays fall obliquely at northern and southern latitudes, however, dumping slightly less energy, i.e. heat, into the atmosphere.

“The prevailing winds in Maine develop in association with large-scale atmospheric shifts driven by seasonal changes in solar heating,” explained Sean Birkel, Research Assistant Professor at the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute, and Maine state climatologist.

When air is warmed, it expands and rises. Cooler air moves in to replace that rising warm air. This action, called convection, means that colder air from the north and south poles constantly moves toward the equator. As the designer and visionary Buckminster Fuller succinctly put it, the wind doesn’t actually blow, it sucks. Wind arises from pressure differences—denser air is sucked from a high- to a low-pressure area.

Keep in mind, however, that the earth not only is round, but it spins, from west to east. That creates a motion called the Coriolis effect. Things in motion, such as a current of water or rising column of air, are pushed to the right (in the northern hemisphere). So instead of making a straight line from pole to equator, the winds track to the right; at our latitude that means they come primarily from the southwest.

But wait, there’s more to the story. Now the jet stream comes into play. The jet stream is a high-altitude river of air that flows from west to east. It does not remain in a constant position over North America but instead tracks north and south depending on the season.

“In summer, the thermal equator and westerly jet stream are shifted northward, whereas in winter these systems are shifted southward,” Birkel said. The jet stream’s southward movement in the winter means low-pressure systems can pull cold dry air down from Canada. When it moves northward during summer months, the jet stream allows subtropical high-pressure systems to draw moist air from the south across New England.

But all these grand movements of massive amounts of air are tempered in Maine by a single fact: the state borders the Atlantic Ocean, which remains cold for most of the year. The cold ocean water is responsible for one of the coast’s distinctive features—the sea breeze. “A sea breeze happens when the air of the land heats up more than over the water. The warmer air draws the cooler air in from the ocean,” explained John Jensenius, a National Weather Service meteorologist in the Gray office. “The opposite happens at night when the air over the land cools and moves toward the sea.”

Maine sailors know that during the summer there are days made hazy by the “smoky southwesterlies.” In part those winds come from a large high-pressure system that parks itself off the East Coast in July and August, known as a Bermuda high. The air moving clockwise around the high brings humid air from the south into Maine, often leading to days of mist and fog.

And come winter? “Typically when a low-pressure system moves along the east coast, Maine will get a nor’easter,” said Jensenius. “We stick out into the ocean and that combined with the low pressure means northeast wind and snow.”

Melissa Waterman is a freelance environmental writer based in Rockland.

For an animated view of the winds prevalent in New England visit the Climate Reanalyzer site, produced by the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine: https://climatereanalyzer.org