Illustration by Caroline Magerl

Illustration by Caroline Magerl

First off, there’s the laundry and the blood. Sometime around late May, I have to start washing his clothes separately from mine. They can go in with the dog blankets, yes, but then I tend to feel bad for the dogs.

My husband’s daily wear is far from CEO-like, even though he’s the boss of dozens and he hobnobs with millionaires and movie stars. Nor is his look “Casual Friday.” His go-to outfit consists of a seemingly moth- and mouse-eaten maroon sweatshirt that he bought at Goodwill ten years ago atop tattered and splattered pants bought as “good pants” from Old Navy—he has no more “good pants,” we discover when we’re invited out to dinner. His pants have holes at the thigh where battery acid has rubbed the cloth away as he lugs batteries up the dock to be recharged. To top off this sartorial splendor, he sports an ancient Pendleton Yacht Yard ball cap with a grime- and sweat-stained brim.

He wears this same get-up for weeks on end and sees no reason to change when it’s just going to get dirty again. I cover the chair he sits in at home with an old dog blanket. Then one night, when I can’t stand it any more, I steal out of bed after he’s fallen asleep to rummage through the pile he has dropped in a heap. I slip the belt out of its loops, fish his phone, some loose change, odd screws, and wallet out of his pockets, and place all atop a clean pair of pants in the hopes he won’t notice the switcheroo. I sneak to the washer with the whole mess to get it all wet so he has no chance of wearing it the next day. He does, after all, have plenty of other stained and soiled (but clean) clothes.

And he’s bleeding. There’s always blood, he never knows from where. It may be a scrape on his forearm or a long gash on his shin. He forgets how it happened. Maybe leaning into a too-tight engine compartment. Or getting caught between a dock and a hard place, or an engine cover and an engine. Or trying to wrench free the frozen controls of the Lull, the Brownell, the Genie Lift. Bruises the size of turkey platters wrap around his hip where he used his body as a lever or a vice to pry or press.

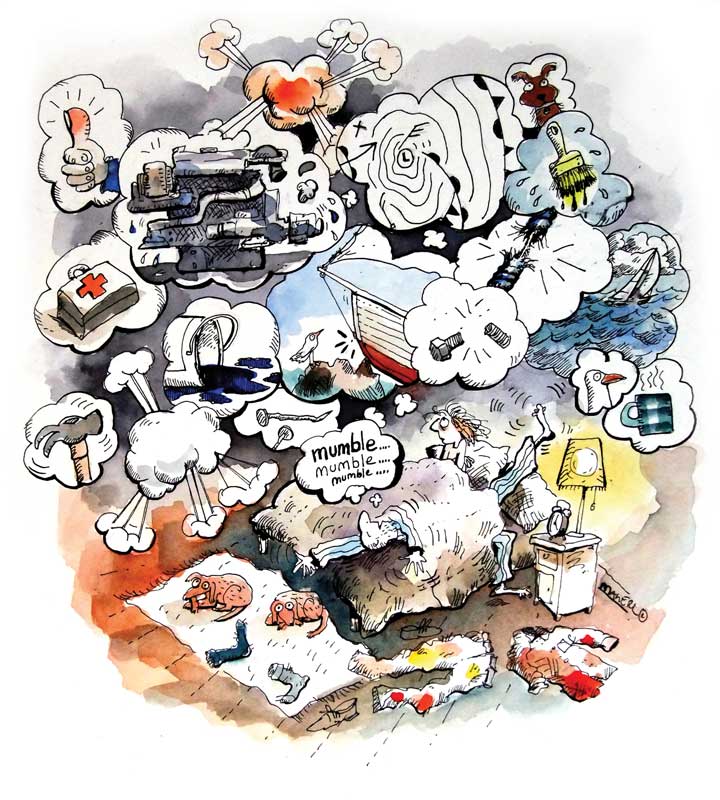

His sleep is riven with nightmares of just-launched 12½’s taking on water, the pump not keeping up, the sawdust applied to the seams not taking. He startles awake at the memory of needing to remember to find the missing sails for Mrs. A’s boat. Maybe they ended up in the spar shed or in the back of the Ford Econoline for reasons no one can fathom. Must look tomorrow. Which, it turns out, is already today.

At 4 a.m., the neighbor’s rooster bugles his Reveille and Stan wonders if he put the topping lift on the mast when he rigged that boat last night. And oops, he forgot to tell Gabe, the son who’s taking over the business, that Marie called three days ago from the Loire Valley in France and wants all her boats in the water by next weekend. And why won’t Tom, one of the wealthiest men on the planet, ever, ever, EVER pay his bill on time? To “sleep” with my husband in spring is akin to sleeping with a colicky baby, all twitches and tossings and occasional cries of pain.

He’s up and out by 6 a.m., “dressed for success,” he says with a smirk. I’ll see him again briefly around 5 p.m. when he dips in for supper and wine, then goes back to work for a few hours, to work the tide, to splice some lines, to rig a boat in the gloaming. To bed by 8 p.m., to sleep, perchance to remember something he forgot.

When I ask at supper how his day was, he replies, “Shot out of a cannon” and then trails off, praying I let him look at his computer instead of making him talk. When I ask whom he interacted with, he gazes into the distance and replies, “I don’t remember.” He can’t remember if he had lunch. When I ask what he did all day, he says, “What didn’t I do?” and goes mute.

Our conversation is pure New England Workingman’s Dead: Mutha brightly trying to engage and help debrief, Fatha retreating further into the morass of details that consumed his day in the hopes it’ll bury him in oblivion.

It’s not like nothing ever happens. I’ll learn months later, from a friend at a cocktail party, that so-and-so who has worked for us for 20 years, had a heart attack and had to be ambulanced to the mainland. That Ricky’s wife had twins after an eventful labor. That Jack doesn’t work at the yard any more, and why not is unclear.

We just have different interests. I like the people side of the business and he likes the mechanical side. If I can stand to hear how he got the goddamn engine running, I will be the lucky winner of a half hour’s detailed depiction of “Then I got a 9⁄16th-inch wrench instead of the 5⁄8th’s that I was using…” until my eyes glaze over. He could knock a Nascar mechanic unconscious with his recitation of technical success stories.

When he tells strangers that he owns a boatyard, they get all moony. They picture Stan as a cartoon character, seated in a rocker by a woodstove in a workshop with wood shavings curling at his feet as he hand-planes a miniature hull, a pipe between his teeth and a sailor’s cap askew on his quintessentially Yankee pate. Sigh. As if.

“What a GREAT job!” they gush. “And you get winters OFF!!”

We are sad to disillusion the dreamers. The romance of the sea is potent stuff, but it needs to be thinned with a dram of the truth. We rarely build boats. We fix, paint, varnish, retrofit, launch, and haul them. Electronics are installed to keep yahoos from running up on ledges. Propellers are replaced after yahoos mangle them on ledges. Holes are patched after yahoos unwittingly carve them on ledges.

Once in a while my husband has to replace a yahoo himself or—in his words—he “fires” a client. Why? For having a crap boat and blaming the boatyard for it. For not knowing that Stan’s grandfather and father worked for the client’s grandfather and father, and that implies a certain mutual respect. For not knowing or caring that Stan goes to a client’s dock to vacuum the seaweed out from between the planks so it looks good in the live feed streaming to the guy’s home in LA. For not assuming that Stan goes back down to the yard after a 12-hour day to splice fender lines so the client and his boat will look all yachty when tied up at the club. Stan wants the boater to look good, even though he himself may look a little ragged. He bleeds so the client doesn’t have to.

The romantics conjure an image of the boatyard buttoned up for winter, the employees miraculously finding other jobs for seven months in rural Maine, or perhaps enjoying down-time at home with a cribbage board, Food Stamps, and a bottle to warm them day after frigid day until the thaw. Truth be told, son Gabriel mans the yard through the coldest months and beyond, keeping 15 to 20 workers busy indoors all winter, fixing what’s broke, gussying what needs gussying, transforming the humblest of crafts into yachts.

Now, after 50-plus years of Spring Madness, Stan and I take a couple of months off each winter, to fulfill the dreamers’ dreams and our own. We find ourselves a sunnier clime, most always near water, often in big cities in foreign lands.

How does Stan adjust, away from his life’s blood, his one true love, the yard? Easily. The key is to hide his maroon sweatshirt long before we go and order a couple of pairs of “good pants” for the duration. He carries the yard in his heart… and on his head, wearing his PYY hat, grease stains and all, to France, California, Guatemala. He’s easy to spot in the Louvre, or jogging along the Seine, or analyzing someone else’s Travelift on San Diego Bay. He stands out when he’s away, looking ever the Mainer, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Diana Roberts lives on Islesboro with her husband Stanley Pendleton, proprietor of Pendleton Yacht Yard, and attributes her long and happy marriage to a highly refined sense of humor.