All images courtesy James Fitzgerald Legacy Collection

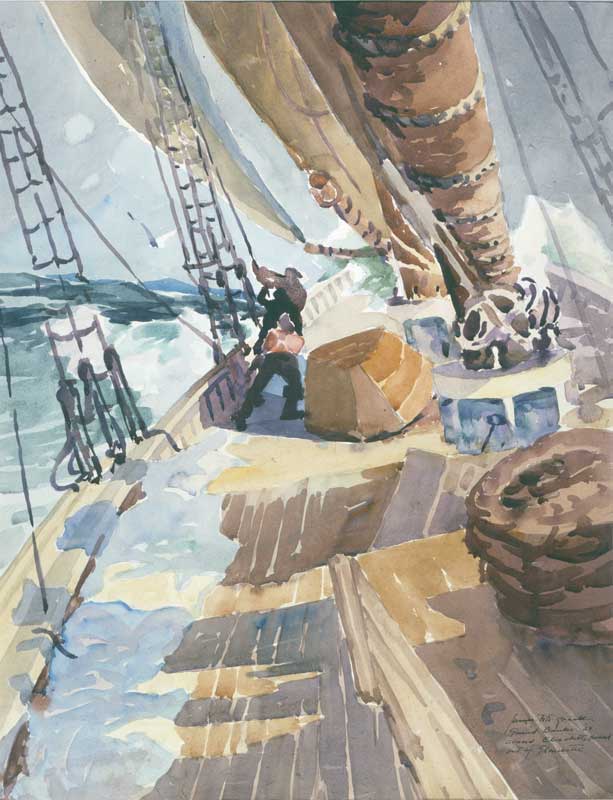

Fitzgerald went to the Grand Banks aboard this commercial fishing ship in 1923. Aboard the Elizabeth Howard, 1923; watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 21½ x 16½ inches. Private collection.

Fitzgerald went to the Grand Banks aboard this commercial fishing ship in 1923. Aboard the Elizabeth Howard, 1923; watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 21½ x 16½ inches. Private collection.

Over the years, painters’ reactions to Monhegan Island have been enthusiastic. In a letter to his wife Emma in 1911, George Bellows expressed his awe in this simple testimonial: “[Monhegan] is possessed of enough beauty to supply a continent.” Writing about the island in his 1955 autobiography It’s Me, O Lord, Rockwell Kent echoed that thought. Monhegan, he wrote, “was enough for me, for all my fellow artists, for all of us who sought ‘material’ for art.”

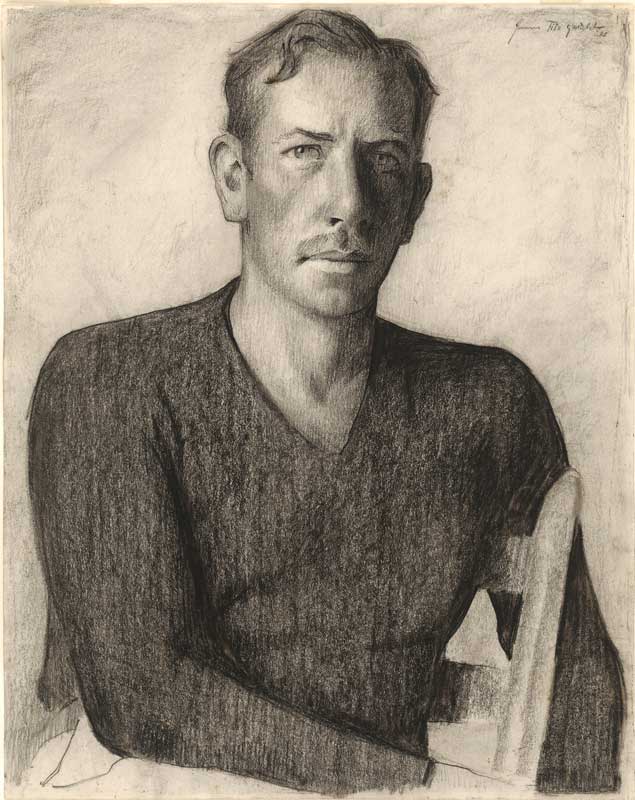

Fitzgerald befriended the writer John Steinbeck while living in Monterey in the early 1930s. John Steinbeck, 1935, charcoal on paper, 24 x 19 inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Hubert, NPG.72.99The painter James Fitzgerald (1899-1971) first visited the island in 1924, a two-week stay that stuck with him through ensuing adventures at sea, stints in Boston and Monterey, California, (where he became friends with John Steinbeck), and while working for the WPA Federal Art Project. He returned to Monhegan in 1937, spending that summer and the next painting there.

Fitzgerald befriended the writer John Steinbeck while living in Monterey in the early 1930s. John Steinbeck, 1935, charcoal on paper, 24 x 19 inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Hubert, NPG.72.99The painter James Fitzgerald (1899-1971) first visited the island in 1924, a two-week stay that stuck with him through ensuing adventures at sea, stints in Boston and Monterey, California, (where he became friends with John Steinbeck), and while working for the WPA Federal Art Project. He returned to Monhegan in 1937, spending that summer and the next painting there.

Like Bellows and Kent, he was enthralled by the place. So much so that in 1943, he sold his studio home in

California and moved for good to Monhegan. Like a few other hardy painter souls—among them, Kent, Jay Connaway, Samuel Rolt Triscott, and the aptly named Andrew Winter—he became a year-rounder. Thanks to him and his hearty brethren, we know how beautiful the island is after a snowfall, and how rugged life is 12 miles out to sea in the middle of February.

The island became Fitzgerald’s principal muse, rivaled only by Mount Katahdin, which he visited nearly every fall. Certain island motifs recurred from year to year: the lighthouse flashing across the night sky, boats anchored in the harbor, fishermen and fish houses, surf crashing on rocks, and sea gulls.

Many of Fitzgerald’s island pieces are reproduced in Robert Stahl and company’s magnificent new monograph, James Fitzgerald: The Drawings and Sketches, published by the James Fitzgerald Legacy of the Monhegan Museum of Art and History. The title is somewhat misleading, for in addition to hundreds of studies, the hefty volume includes a multitude of finished watercolors and paintings representing the fruit of his efforts to render the essence of a subject.

The Monhegan Light as viewed from the north lawn of Lighthouse Hill. Lighthouse Monhegan, 1950s, watercolor and Chinese ink over graphite on paper 22½ x 28 inches. Private collection.

The Monhegan Light as viewed from the north lawn of Lighthouse Hill. Lighthouse Monhegan, 1950s, watercolor and Chinese ink over graphite on paper 22½ x 28 inches. Private collection.

In his introductory essay, art historian Bruce Robertson offers an overview of Fitzgerald’s life, beginning with his birth in South Boston into an Irish Catholic family. At a young age Fitzgerald was given his own space to work on his art and also was allowed to skip church activities—an unusual dispensation at the time.

He went on to study at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he learned the art of gilding. Following graduation, he went on several extended ocean voyages, including a trip to the Grand Banks. These experiences gave his images of seafaring life a special authenticity.

The solitary figure braving a fierce winter nor’easter in Monhegan in Winter, 1959, is said to be Captain Manville Davis, an island fisherman. Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 19½ x 25¼ inches. Photographed by Jay York. James Fitzgerald Legacy Collection.

The solitary figure braving a fierce winter nor’easter in Monhegan in Winter, 1959, is said to be Captain Manville Davis, an island fisherman. Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 19½ x 25¼ inches. Photographed by Jay York. James Fitzgerald Legacy Collection.

Watercolor became Fitzgerald’s favorite medium; over time, he developed into one of its most versatile practitioners. As Robertson explains, watercolor for modernist artists “was an expressive, intimate medium not bound by the same rules and expectation as oil painting.” Comparing Fitzgerald’s work to that of Winslow Homer, he calls it “simpler,” but “every bit as forceful.”

Fitzgerald’s approach to painting the landscape had its roots in Eastern thought and aesthetics. He was known to spend hours absorbing a scene before going to his studio to begin his work. At the same time, he had a remarkable memory for motifs; his ability to return to a subject years later and create it anew and afresh was remarkable.

Writing about Fitzgerald’s drawings, Portland Museum of Art Curator of American Art Karen Sherry refers to his “reverence for place.” He brought that reverence to bear on other places in the world, most notably Peggys Cove in Nova Scotia and the Aran Islands off the coast of Ireland—both locales, it should be noted, that recall Monhegan in their topographies and fisherfolk.

Fitzgerald did many sketches and paintings of Mount Katahdin, which he first visited in the mid-1940s and returned to on an annual basis over the last 25 years of his life. The painter drew visual and spiritual sustenance from his stays at the Katahdin Lake Camps. He painted the mountain shrouded in clouds or lit up pink in alpenglow, in autumn regalia, or covered in snow. In a letter written in September 1967, he acknowledged the mountain’s grip, referencing the Native American spirit that guarded the mountain: “The ancient God of Katahdin, Pomola, is after me. Hard adversary but I’ll hang on.”

Fitzgerald was also an animalier, an artist of animals, of the first order. From a fierce-eyed tiger and thrashing sharks to the noble haunches of working horses and oxen, he could capture a creature’s spirit. He also painted the female nude, often rendered in erotic poses.

Fitzgerald made several studies of Monhegan dorymen for his painting Night Riders, including this one in black ink on paper, 1947. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Hubert, 1992

Fitzgerald made several studies of Monhegan dorymen for his painting Night Riders, including this one in black ink on paper, 1947. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Hubert, 1992

Fitzgerald’s legacy as a painter owes a great deal to his friends Anne and Edgar Hubert who supported him in his lifetime and were devoted to preserving his art. The painter’s estate was later passed on to Stahl, who has done an impeccable job recording and interpreting the work. To date, more than 1,900 images have been professionally photographed and many are available for viewing online at www.jamesfitzgerald.org, which was launched in 2012.

The common denominator in Fitzgerald’s art was his ability to find the essence of a subject without being distracted by detail or drama. As Anne Hubert wrote so eloquently, “It’s easy if the surf is pounding and it’s 50 feet high to be impressed, but you really can be equally impressed with just the light on a little patch of water.” The artist put it this way: “Simple realism isn’t enough…pure painting is concerned with timelessness.”

Carl Little has contributed essays to Philip Frey: Here and Now (Marshall Wilkes) and Nature Observed: The Landscapes of Joseph Fiore (Falcon Foundation). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

The Monhegan Museum of Art: Happy 50th

A writer once said of Monhegan that there might not be any single square mile more important to American art. That legacy is showcased in the Monhegan Museum of Art, which this summer celebrates its 50th anniversary with a major exhibition and a catalogue, “The Monhegan Museum: Celebrating Fifty Years.”

The museum is also hosting a lecture and a film series as well as a “Golden Jubilee” party at its location on Lighthouse Hill on August 1. With the 50th anniversary of James Fitzgerald’s death drawing nigh, it is also fitting that the museum will present a special exhibition of his work in his former studio in conjunction with the festivities.

Twenty years ago, when the museum turned 30, I attended a celebration of its expansion. Museum Director Edward Deci, painter Jamie Wyeth, and others took turns highlighting the history of the museum with its marvelous mission. In my own remarks that day I paid tribute to the philanthropist Elizabeth Noyce (1930-1996) who had helped the museum with a significant challenge grant. Noyce collected a number of island paintings over the years, some of which ended up in the Monhegan Museum’s permanent collection. More recently Jamie Wyeth and his wife, Phyllis, have supported the cause with a $1-million challenge grant from the Wyeth Foundation toward a $4-million fundraising campaign.

Despite its small size, Monhegan has had “an outsized influence on American art,” Deci said recently. Indeed, one can trace the history of the country’s landscape tradition in the work inspired by this one island. He also highlighted the special appeal of the museum’s location: “We offer visitors the rare opportunity to experience these defining works of American art within the setting that inspired them.” That is truly remarkable. —CL

“The Monhegan Museum: Celebrating Fifty Years” is up through September 30, 2018. For dates and information about 50th anniversary events, visit www.monheganmuseum.org.