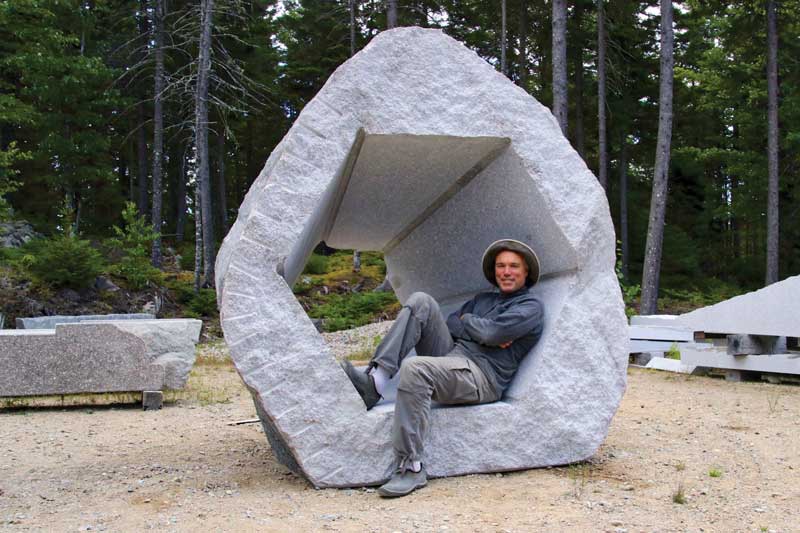

A smiling Jesse Salisbury reclines inside part of the commissioned sculpture he will install at the Falmouth Public Schools this spring. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

A smiling Jesse Salisbury reclines inside part of the commissioned sculpture he will install at the Falmouth Public Schools this spring. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Memorials to fishermen who have lost their lives at sea must fill more than one role: they must honor the lost individuals and at the same time inspire awe for their dangerous profession and for the ocean.

That was sculptor Jesse Salisbury’s challenge when he was commissioned to make Lubec’s Lost Fishermen’s Memorial.

The Lost Fishermen’s Memorial in Lubec, designed by Jesse Salisbury. The names of the fishermen are inscribed on the walls between the wave shapes. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

The Lost Fishermen’s Memorial in Lubec, designed by Jesse Salisbury. The names of the fishermen are inscribed on the walls between the wave shapes. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

The result, unveiled last summer, consists of two sets of smooth, wave-shaped granite walls divided by a walkway and overlooking the harbor. The inside walls are inscribed with the names of 102 fishermen who lost their lives on the waters off Washington County, Maine, and Charlotte County, New Brunswick.

While creating this remarkable piece, Salisbury envisioned the whole landscape as a work of art. “From a distance it’s just a sculpture,” he said, “but when you walk through it, it’s this intimate space.” He and his father, Jim Salisbury, who often assists with siting his son’s work, designed a walkway and a 22-foot-long curved wall embankment to go with the piece. The memorial and its surrounding park succeed in referencing the magnitude of man’s relationship with the sea, as well as providing a place for personal reflection for relatives of those who have died.

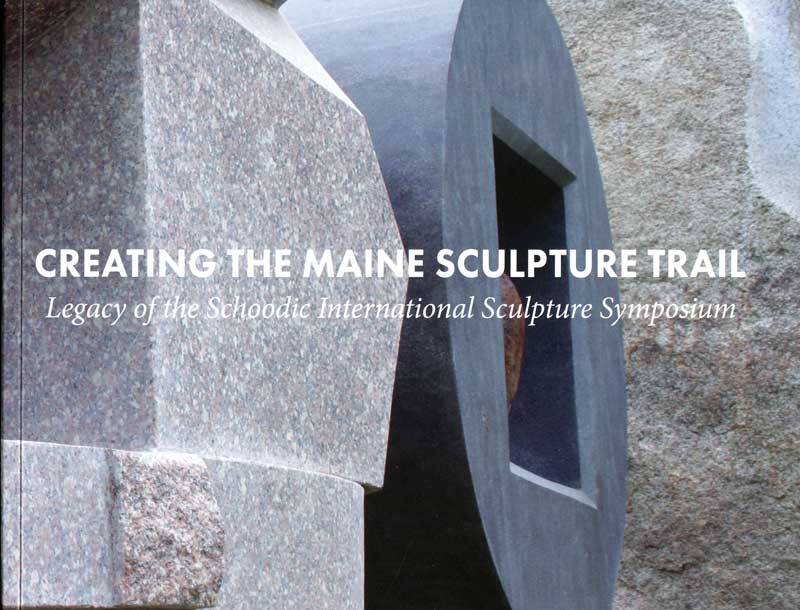

Salisbury was a fitting choice for the memorial. He previously oversaw the creation and installation of 34 public granite sculptures made by artists from all around the world as part of the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium. The biennial symposium, which took place between 2007 and 2014, was his brainchild, with help from his wife Kazumi “Hoshi” Hoshino. Hoshino is also a master stone sculptor and has a number of prestigious public commissions to her name. The two might arguably be called the first couple of Maine sculpture.

Hoshino and Salisbury met in 2004 at an international sculpture symposium in ŌO–tawara City in northeast Japan and fell in love over the course of the six-week gathering. They married in Kyoto in early 2006 and settled in coastal Steuben, Maine, where Salisbury’s family lives.

Kazumi Hoshino working in the couple’s Steuben studio on a block of granite that became Composition Elements. The finished piece is now sited in the lobby of the New Balance Student Recreation Center at the University of Maine. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Kazumi Hoshino working in the couple’s Steuben studio on a block of granite that became Composition Elements. The finished piece is now sited in the lobby of the New Balance Student Recreation Center at the University of Maine. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

While rooted in downeast Maine—their children, son Ren, 11, and daughter Miyabi, 5, attend the Peninsula School in Prospect Harbor—both artists also have deep ties with Japan. Born and raised in Nagoya, Hoshino graduated from the Tohoku University of Art and Design in 2000 and has exhibited widely in Japan. Salisbury, who was born in Steuben and raised in Portland, Maine, first went to Japan as a teen. His father was fisheries attaché for East Asia and worked at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. After finishing high school there, the young Salisbury stayed another year to apprentice with a Japanese potter before returning to Maine to attend Colby College, where he first began sculpting in granite. After graduating in 1995, he returned to Japan to be a carving assistant and Japanese-English translator at the Yonago International Sculpture Symposium. This symposium and a later one in New Zealand helped inspire the Schoodic Symposium.

Several models for larger pieces in the Steuben studio, including Salisbury’s Lost Fishermen’s Memorial (left) and Hoshino’s Composition Elements. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Several models for larger pieces in the Steuben studio, including Salisbury’s Lost Fishermen’s Memorial (left) and Hoshino’s Composition Elements. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Hoshino and Salisbury strengthened their ties to Japan in recent years, setting up a winter studio in a former factory on Kitagi Jima, part of the vast archipelago in the country’s inland sea. Salisbury described the island as “the Vinalhaven of the inland sea” because of its history of quarrying, which dates back to Japan’s castle-building era in the 1600s. “They shipped stone all over the world,” he explained. A granite mountain rising out of the sea, the island remained active as one of the largest manufacturing centers for stonework into the 1980s and 1990s. Today only a few quarries still operate, along with a number of factories involved in stone processing.

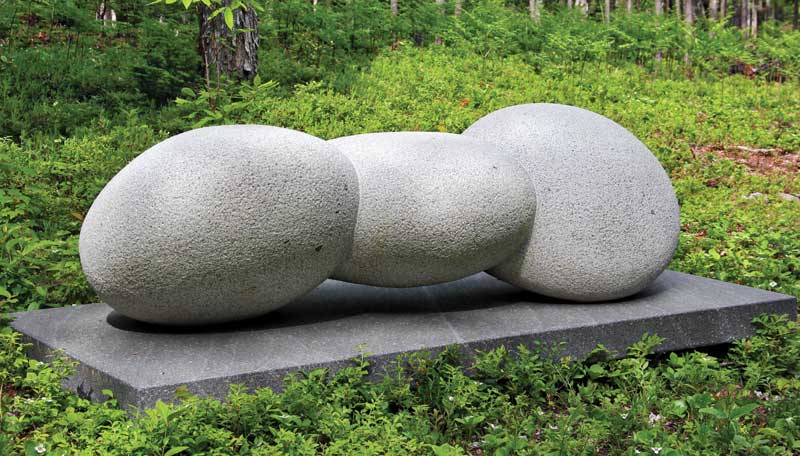

In recent years Hoshino has been working on what she calls her “Composition” series, combining simple rounded forms in various arrangements. She credits her love of these shapes with her upbringing in Japan, embracing its traditional sense of finding beauty in simplicity. For her, carving stone is an exploration of time and self-discovery and a way of opening herself more to the world. She does a lot of hand-texturing, which gives the stone a soft quality.

Kazumi Hoshino’s piece Composition Trio, 2017, made from Sullivan granite. The piece reflects her reverence for simplicity. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Kazumi Hoshino’s piece Composition Trio, 2017, made from Sullivan granite. The piece reflects her reverence for simplicity. Photo courtesy Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino

Hoshino was artist in residence in the sculpture studio at the University of Maine last May, part of a visiting artist program supported by the Littlefield Gallery in Winter Harbor. She and Salisbury were both featured in “Carved Stone: Maine Artists” in the Lord Hall Gallery at UMaine last fall. One of her pieces in the show, Composition Elements, was the model for a sculpture now in the lobby of the university’s New Balance Student Recreation Center. She recently won a Percent for Art commission to create a sculpture for UMaine’s new Plant, Animal and Insect Laboratory. She picked out the granite and began the piece, titled Biosphere, before heading to Japan last winter, and will finish the work this spring.

If Hoshino’s work is sometimes referred to as intimate, Salisbury’s tends to be bold and rougher around the edges. Beach Pea, 2004, one of three of his pieces installed at the Portland International Jetport, exemplifies that contrast, its five rounded stones encased in the rough-hewn pod. Often his works include the marks left by chisels used to split the massive pieces of rock. He has said his sculptures are intended to show glimpses of the movement of the earth’s crust and geologic time.

Motion, 2006, by Jesse Salisbury, was carved from one block of Jonesboro granite. Photo by Polly SaltonstallRecently, Salisbury has been working on a large privately funded public art piece for the Falmouth Public Schools. The 12-foot-high columnar tower and its related pieces were cut from a single 26-ton glacial erratic retrieved from a blueberry barren. In conjunction with the project, he visited the K-12 school to talk with students about stone-splitting and the history of quarrying in Maine, including geology, water technology, and geometry in his presentations.

Motion, 2006, by Jesse Salisbury, was carved from one block of Jonesboro granite. Photo by Polly SaltonstallRecently, Salisbury has been working on a large privately funded public art piece for the Falmouth Public Schools. The 12-foot-high columnar tower and its related pieces were cut from a single 26-ton glacial erratic retrieved from a blueberry barren. In conjunction with the project, he visited the K-12 school to talk with students about stone-splitting and the history of quarrying in Maine, including geology, water technology, and geometry in his presentations.

While they have worked in a wide range of stone, the pair shares a deep love for local granite and basalt. “If I lived in Italy, maybe I would work in marble,” Hoshino said. As it is, granite is her favorite. She loves the variety of colors, the grain, and character.

Salisbury and Hoshino mainly draw from area quarries for their rock, sizing up the raw material in the planning process for each piece. For bigger projects they almost always must find fresh stone. “The rock in old quarries tends to be quite small when you true it up to its proper size,” Salisbury explained. They cut the massive stones and shape them in their large 32-by-64-foot studio in Steuben, which features a huge industrial cutting saw.

Even as Salisbury has immersed himself in the history of quarries and the traditional ways of cutting stone, he has also welcomed new technology, including the CAD program used by architects. The program came in handy in designing the Lost Fishermen’s Memorial. “It’s an incredible tool,” he said: “You can show a work in 3-D and animate drawings.”

When asked what it is like to be married artists working in the same field with the same material, the two are kind enough not to groan—Salisbury said they get that question a lot. They are not competitive, he explained. They help one another with technical things to keep the other’s project moving along, but they don’t collaborate. They are, you might say, granite companions.

Carl Little’s Paintings of Portland, co-authored with his brother David, is forthcoming from Down East Books.

Jesse Salisbury and Kazumi Hoshino are represented by June LaCombe Sculpture in Pownal and Courthouse Gallery Fine Art in Ellsworth.

A new book, Creating the Maine Sculpture Trail: Legacy of the Schoodic International Sculpture Symposium (2017; $38, www.mainesculpture.org) chronicles the five symposiums Jesse Salisbury directed between 2007 and 2014. Each six-week symposium included artists from around the world, who were chosen by a jury, and hundreds of volunteers. The works were made in a large public area, and eventually were placed in downeast communities, where they form the Maine Sculpture Trail. The book recounts the symposium’s history and profiles each of the 34 works of art and its maker.