Illustration by Ted Walsh

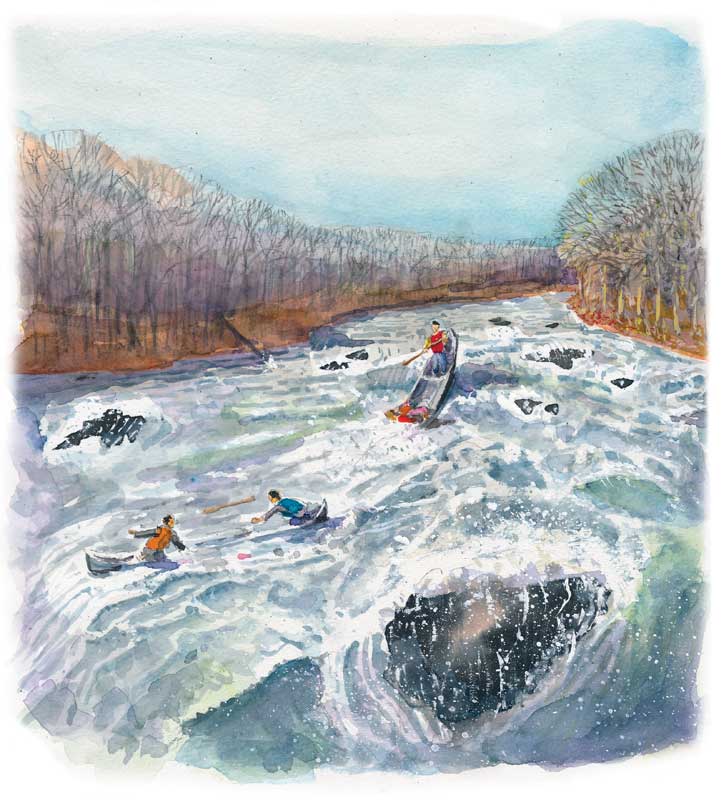

An early spring canoe trip turns into disaster and teaches valuable lessons.

An early spring canoe trip turns into disaster and teaches valuable lessons.

The plan, hatched over beers a few nights earlier, went something like this: on Saturday, April 20, 1974, two canoes, each carrying two young men, ages 22 to 26, would put in below a dam in Farmington Falls, Maine, and float down the Sandy River to Mercer, a distance of approximately 10 miles.

According to a U.S. Geological Survey gauging station, that day the flow on the Sandy was 3,650 cubic feet per second (cfs), which was 12 times more powerful than the flow measured later that summer. The water temperature was 38 degrees.

A string of sunny days with upper-50-degree air temperatures had tricked Robert Joseph, canoe trip leader and my oldest brother, into thinking that paddling the river would be a “fun adventure.”

Robert and my twin Don, a senior at Colby College, were in one canoe. George Joseph and Rusty Cyr would paddle the second canoe. No one had white water paddling experience. Nor had they scouted the river, consulted river maps, sought tips from experienced canoeists, or paddled the river in calmer waters. Wearing PFDs was the single wisest decision made that morning.

Emergency assistance, if needed, was not readily available; my brothers and their friends had not notified Maine game wardens of their plans. No other canoeists dared paddle the Sandy that day due to near-flood-stage waters. The four planned to blindly canoe a rural section of a dangerously high and swift river.

The first quarter mile was deceptively fast and smooth. Amid shouts of joy, the canoeists were giddy. Their euphoria, though, was short-lived.

“It didn’t seem possible, but our canoes suddenly picked up speed. We heard the roar of rapids ahead. We had to yell to communicate,” recalled Don.

“I was in the stern with Rusty in the bow,” remembered George. “Entering the first stretch of white water, we had no idea what was about to happen. Rusty turned around, smiled and yelled, ‘Here we go!’ Our canoe swallowed a lot of water but we made it through the run.”

They wanted to go ashore to bail the canoe, but one bank was too steep, and paddling the half-sunk canoe to the other side against the strong current was too difficult. “Rounding a bend, we heard the roar of the next rapids,” said George. “Within seconds the canoe hit a huge curl and plunged bow-first into a big hole, dumping us into the river. We came up and grabbed the gunwales. The rapids, known today as Hell’s Kitchen, battered us. It was difficult keeping our heads above water. Remembering what I was taught, I yelled, ‘We should stay with the canoe.’ Rusty looked downstream at an approaching set of rapids and yelled, ‘I’m headed to shore.’ That was the last time I saw him for the next couple of hours.”

Forty-two years later, George remembers the experience like it was yesterday. “Life-threatening events like this stay with you. Our canoes were 16-foot aluminum Grummans with keels. We couldn’t have chosen a worse canoe for Class 3 and 4 white water.”

On the right side of the river and slightly behind the lead canoe, Robert and Don watched George and Rusty struggling in the rapids. “Our canoe also filled with water,” recalled Don. “Our gear floated inches below the gunwales. I jumped into the river because the canoe, instead of skimming boulders, was now hitting each one head-on or broadside.”

When the canoe squarely hit the first boulder, Robert flew forward, smashing his forehead on a thwart. Don, holding onto the gunwale of the downriver side of a quartering canoe, could hear and feel the deep thumping of aluminum pounding boulders. “I let go out of fear of being crushed between a heavy canoe and a boulder. I tried swimming to shore but the current dragged me to the middle of the river.”

The shock of frigid water caused him to hyperventilate; within minutes his limbs and jaw muscles barely functioned. Entering a whirlpool, Don was sucked to the river bottom, tumbling and bouncing on rocks in his PFD. “Once free of the turbulence, I righted myself,” he added. “I felt the bottom of the river and pushed myself to the surface. I gulped several breaths of air, not knowing if or when there’d be another opportunity. I was terrified, struggling to keep my wits, and feeling helpless.”

An eddy dragged him under and when he popped up, George’s canoe—still upright—was within reach. He held onto the gunwale with his left elbow because neither hand functioned. “In the chaos,” Don remembered, “George yelled at me to stay with him. But I let go after hearing the roar of yet another set of rapids. Events were coming at me very fast, but they appeared in slow motion.”

A star football player at Colby (Legendary Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry sent Don an invitation to Texas for a tryout), Don relied on a technique he’d been taught by Colby Coach Dick McGee: “I blocked out the fear and concentrated on keeping my head above the waves, breathing slowly, remaining calm, and making every effort to reach shore.”

His poise paid dividends; he dog-paddled and breast-stroked to within a few feet of shore. “The bank was agonizingly close but the current was so strong,” said Don, “and my arms and hands were so cold and weak I couldn’t grab the bushes racing through my fingers. In desperation, I tried biting small branches raking my face, thinking that if I could hold a branch with my teeth, it might swing me to shore, but that too failed.” The river deposited him onto a sandbar where he collapsed in exhaustion.

Like Don, George, still clinging to his canoe, had been in the river for about 25 minutes—the upper limits of human survival in 38-degree water. “I was starting to lose my judgment,” said George. “Hitting another curl, the canoe and I went under and I came up without my eyeglasses. So, I abandoned the canoe and headed for the east shore. From what I remember—my mind and eyesight were blurry—I think I helped Donnie off the sandbar.”

Shivering uncontrollably and incoherent, Don tore off his wet shirt with his thumbs. “I don’t remember George helping me or landing on a sandbar,” he said. “But I do remember the sun’s warmth. It felt heavenly.” Hypothermia, he learned later, plays weird mind games. “Bobbing and tumbling in frigid water, I kept repeating to myself, ‘Hold it together. I’ve got a dance date tonight with a beautiful Colby coed.’”

Rusty reached shore first, minutes after his canoe was swamped. Robert and his mangled canoe beached 15-20 minutes after launching. “With Rusty safely ashore,” remembered Robert, “I jogged past patches of corn snow to rescue Donnie and George, but I had lost sight of them.” After what seemed an eternity, Robert found George, dazed and confused, sitting on the riverbank. “I was panic stricken,” added Robert, “because I couldn’t see my brother. I yelled at George, ‘Have you seen Donnie? Have you seen my brother?’” George mumbled, “He’s right here.” Don was prostrate in a patch of brown matted grass.

“George and Donnie were in really bad shape,” said Robert. “I ordered them to help me drag my canoe up the river bank, thinking that physical exertion would generate core body heat. The three of us pulled the canoe uphill to a hayfield.”

All four reunited at the bridge in Farmington Falls and hitchhiked back to the dam where the canoes were launched and Robert’s truck was parked.

Several weeks later, after water levels dropped, friend Tim Ladd, piloting a Cessna with Robert as a passenger, flew above the Sandy River. They spotted the carcass of the missing aluminum canoe. It was wrapped like a giant U-bolt around a large boulder midstream.

Today, Don, an English teacher at Orono High School, draws on that experience to teach students the importance of planning, personal accountability, and teamwork. “We hadn’t done our homework, such as scout the river from shore or examine river maps,” he tells his students. “Preparation is a cornerstone of success.”

He tells me, “Young people think they’re invincible and immortal. We were that way too. Every high-risk adventure has a dangerously thin line separating exhilaration from the heartache of tragedy. Teenagers and 25-year-olds don’t think about that line. Nor did we.”

Each year when April 20 pops up on the calendar, the four canoeists—now in their 60s—reflect and give thanks that their poor decision didn’t end tragically. “Some years we call each other to check in,” said Don, “because we’re all haunted by vivid flashbacks. How we survived that near-fatal mistake defies explanation. It was as if death stared us in the eyes that day and said, ‘I’m not yet ready to claim you.’”

Writer Ron Joseph of Waterville is a retired Maine wildlife biologist.

Paddling Safety Tips

Canoeing and kayaking are great fun and a wonderful way to access nature. Following these simple rules will help ensure your safety:

- Wear a U.S. Coast Guard-approved PFD with a whistle attached.

- Wear a wetsuit when paddling in 60 degrees Fahrenheit or colder waters.

- Do your homework by studying river guide booklets/maps and quizzing more experienced paddlers.

- Plan your put-in and take-out locations and calculate the distance.

- Tied-down dry bags should include drinking water, food, maps, first aid kit, matches, and extra clothes.

- Do NOT rely on cell phones since coverage is lacking on many rivers.

- Pack throw bags and other rescue equipment.

- File a float plan with a friend or family member with instructions to phone the Maine Warden Service should you not return home on time.

- Know your paddling limits and swimming skills.

- Carry a spare paddle.

- Wear a bright jacket or shirt that can be easily seen in an emergency.

- Pack a bailer or manual bilge pump.

For more in-depth safety tips, visit the American Canoe Association website.