Seasick, she hung on in a pilot berth as we beat up Grand Manan Channel into strong winds, big seas, and thick fog. What a testimony to the Hinckley Bermuda 40 that by the end of the cruise, this friend was enthusiastically lobbying her husband that they, too, should buy one.

This story illustrates why these iconic sailboats have been a brilliant star in the constellation of great Maine-built yachts. Temptation eventually led me to sell, but I might have been smarter to keep the boat.

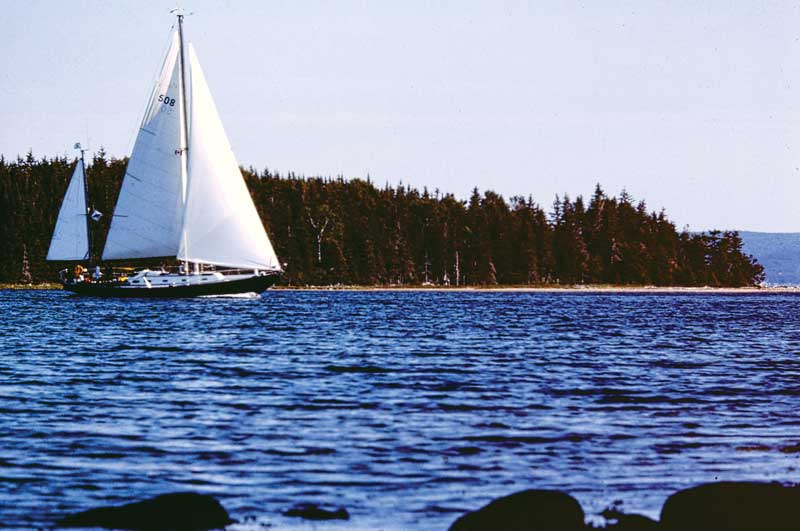

Eggemoggin beats into strong wind and heavy chop in Cape Breton Island’s Bras d’Or Lakes. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

Eggemoggin beats into strong wind and heavy chop in Cape Breton Island’s Bras d’Or Lakes. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

Bermuda 40s, B-40s for short, are relatively well-known to people familiar with cruising sailboats. The Henry R. Hinckley Company of Southwest Harbor launched the first one in 1960. They were of the early generation of fiberglass auxiliary sailboats designed for both ocean racing and cruising, which in that era could be done successfully in the same boat.

To create the B-40, naval architect Bill Tripp, Sr., slightly tweaked his Block Island 40 design. Block Island 40s had appeared in the late 1950s and enjoyed much racing success, the first fiberglass ocean racers to make a name for themselves. A group of sailors impressed by the Block Island 40s had gone to Henry Hinckley for what they hoped would be an even better performing and more elegantly finished near sistership.

The B-40 class has a relatively wide keel-centerboard hull of the type popularized by the famous Finisterre, the only boat ever to win three consecutive Newport to Bermuda races, beginning in 1956. The Cruising Club of America handicap rule then used for racing large sailboats in the United States favored that type of boat. Although long since obsolete in many people’s minds, the type remains popular with many as a pretty and safe boat with a comfortable motion.

B-40s, because of their less than four-and-a-half-foot draft with the centerboard raised, are especially well suited to cruise shallow water areas such as the Bahamas. With the B-40s, the Hinckley Company established its reputation for top-quality, beautifully finished fiberglass sailboats, and the company built 203 of them.

Quality family time on a steep Bras d’Or Lakes beach. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

Quality family time on a steep Bras d’Or Lakes beach. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

I bought ours, which I named Eggemoggin, in 1974. I had owned a wonderful little wooden yawl for the previous four years, but was ready for a boat with more ocean-going capability and family space. I remained dedicated to wood and had been looking at used wooden boats when my friend Bob Hinckley, Henry’s son, telephoned. A 1963 B-40 built for racing with a taller-than-standard rig and additional ballast was coming on the market, having become too much for the aging owner to handle. He quoted a price to Bob that was significantly below market value.

Here was an opportunity fitting my criteria—except for the fiberglass construction. Said masterful salesman Bob, “Sail a nice fiberglass boat for 45 minutes, and you will forget that she is fiberglass.” I went to look at the boat in the Damariscotta River, and bought it with the agreement that the delightful gentleman who owned her might take one last cruise, then leave the boat at Hinckley. Two weeks later she was there, and the yard crew told me that when the seller departed, he had been in tears.

Sad and unusual, yet heartwarming, is that this particular B-40 was cherished and used by two owners who had been handicapped in severe accidents. The man who sold to me was literally a singlehander, having lost an arm in a plane crash. To simplify his boat’s handling, he added a self-tending working jib on a club. Years later, I sold the boat to an exuberant younger man who was partially paralyzed by a car crash not long after his purchase. He kept and sailed the boat for three decades and perhaps still owns her.

He had her trucked to Monterey Bay, California. After his accident, he ordered a new mast with roller-furling mainsail, and he removed the mizzen mast to install a gimballed helmsman’s seat with a harness to hold his upper body snug. As recently as 2010, he sent me photographs of the boat under sail, describing 15- to 20-foot seas in certain months. He wrote, “We are having a lot of fun sailing in harsh weather/big seas in California.” Proudly, he reported sailing the boat 100 to 135 days per year.

Ably handling tough weather was nothing new for this B-40. The worst conditions that I have experienced at sea on a sailboat were aboard the vessel—and on multiple occasions. In 1975 while en route home from a family cruise in Cape Breton Island’s Bras d’Or Lakes, we departed Halifax with assurance from the airport weather office that a tropical storm off North Carolina would track way south of us. It turned due north, developed into Hurricane Blanche, and caught us south of Nova Scotia with hurricane force winds from the southeast opposing the current flowing out of the Bay of Fundy. The distance between waves became extremely short as they shot up to 20 feet or more. The eye of the hurricane passed right over us. In classic fashion, the sun briefly appeared before the 60-knot winds, gusting to about 85, blasted us from the exact opposite direction. Under just a storm jib to keep the boat moving fast enough for rudder control through the deep troughs, where we were blanketed by the steep, high waves, we ran off with the wind on the quarter. The robustly built boat suffered no damage.

Eggemoggin at her best—exploring the Maine coast. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

Eggemoggin at her best—exploring the Maine coast. Photo courtesy Ben Emory

Four years later we raced in a Marion, Massachusetts, to Bermuda race through the most prolonged heavy weather that I have seen on multiple passages between Bermuda and New England. On the return that year, a massive gale as intimidating as the hurricane overtook us. For the only time in my life—and in nighttime pitch black—a wave completely washed over and submerged the boat, the force of the water bending the metal dodger frame flat on the cabin top.

I have a lot of confidence in the heavy weather ability of B-40s! Light-wind performance is their weakness, though, a result of the heavy displacement combined with the long keel with attached rudder. Sailing in such light weather was the beginning of the end for our ownership of our B-40.

We had wonderful family times on board our B-40. In the Bras d’Or Lakes our three-year-old daughter happily took her naps under our feet in the cockpit well as we sailed, and later her little brother’s folding crib kept him contained in a forward berth. We poked the bow into endless Maine coves and many Canadian ones too. All that went out of my mind, though, sitting with sails limp going nowhere in a near-windless Monhegan Race. Sloops with more modern high-aspect rigs and with underbodies sporting short keels and separated rudders started in the class behind us. I watched them overtake us, heeling slightly and making bow waves.

The temptation of these newer, faster craft eventually proved too hard to resist. I let a very good boat go.

Ben Emory splits his time between Salisbury Cove and Brooklin. His book Sailor for the Wild—On Maine, Conservation and Boats is due out in May 2018 through Seapoint Books.