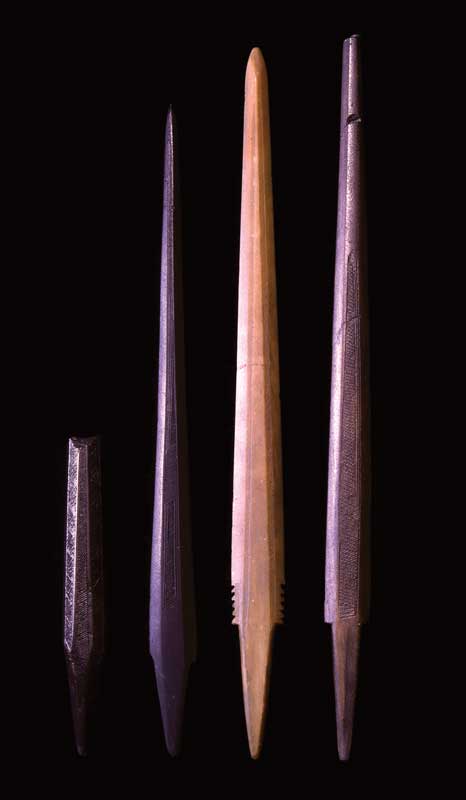

Elegant slate “bayonets” were ground with machine-like precision, sometimes with engraved decoration so minute that most people need a magnifier to fully appreciate it. Though spear-like in appearance, they were too fragile for actual use. Image courtesy Bruce BourqueIn the 1880s, strange prehistoric objects began coming out of the ground from ancient graves in the Penobscot Valley, along with large quantities of brilliant red powder, a form of iron oxide called red ocher. These ancient graves were unlike any elsewhere in North America. As word of their discovery spread, they attracted the attention of America’s pioneering archaeologists, who traveled to Maine from the Smithsonian Institution, Harvard University, and elsewhere to examine them and to search for more. One of these archaeologists coined a name for the people buried in these cemeteries: The Red Paint People.

Elegant slate “bayonets” were ground with machine-like precision, sometimes with engraved decoration so minute that most people need a magnifier to fully appreciate it. Though spear-like in appearance, they were too fragile for actual use. Image courtesy Bruce BourqueIn the 1880s, strange prehistoric objects began coming out of the ground from ancient graves in the Penobscot Valley, along with large quantities of brilliant red powder, a form of iron oxide called red ocher. These ancient graves were unlike any elsewhere in North America. As word of their discovery spread, they attracted the attention of America’s pioneering archaeologists, who traveled to Maine from the Smithsonian Institution, Harvard University, and elsewhere to examine them and to search for more. One of these archaeologists coined a name for the people buried in these cemeteries: The Red Paint People.

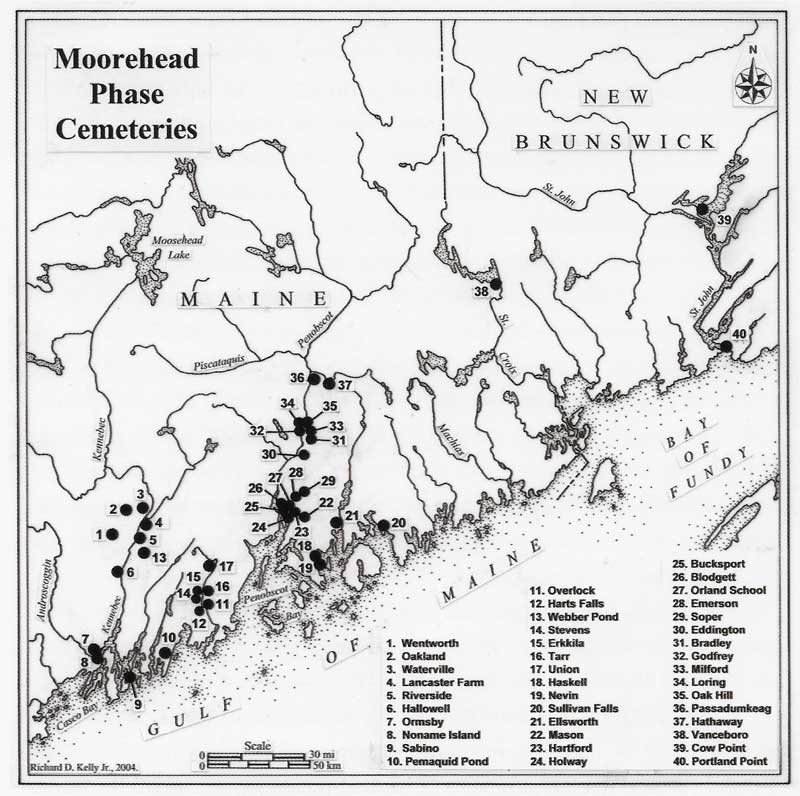

Humans around the world have used red ocher in rituals for a long time, but the large amounts found in these graves is unequalled anywhere. And there are many cemeteries. About 60 have been discovered, from the Androscoggin River to the St. John in New Brunswick.

Special objects found in the graves included figurines of sea birds, seals, porpoise-like creatures, and beavers, the earliest such sculpted forms known in North America. The graves also held objects from far away: beautifully polished slate spear tips from the eastern Great Lakes, over 700 miles to the west, and graceful spear points of a translucent stone called quartzite, commonly known as Ramah chert, which is found only on a single mountaintop 1,000 miles to the north in Labrador. Even the ocher itself must have come from outside Maine, for none occurs within the state.

Taken together, the ocher, the artifacts, the graves, and the cemeteries themselves set the Red Paint People far apart, not only from those who came before them, and those who followed, but from every other known hunter-gatherer group in northern North America.

To archaeologists, cemeteries reveal only a thin slice of a culture. So in the early 1970s I set out to search the coastline for a village of these people. I succeeded beyond my fondest hopes when I pulled my boat ashore in front of a large archaeological site on a property known as the Turner Farm on the island of North Haven in Penobscot Bay.

This kind of site is known as a shell heap because the soil is composed mainly of the remains of many prehistoric clam bakes. The shells change the soil chemistry so that bone is preserved, which allows archeologists to learn what animals were taken and how their bones were used to make artifacts.

The Turner Farm site under excavation in 1972. Accurate recording of the shell heap’s complex layers of refuse required walls, called balks, to be maintained between all excavation units. Image courtesy Bruce Bourque

The Turner Farm site under excavation in 1972. Accurate recording of the shell heap’s complex layers of refuse required walls, called balks, to be maintained between all excavation units. Image courtesy Bruce Bourque

We excavated at the Turner Farm site for five summers between 1972 and 1976, slowly digging down through the many layers deposited over millennia until, at the bottom, we found evidence of the Red Paint People. It was then that we began to truly understand how unusual their lifestyle was and how different their world was from ours.

The first surprise was the abundance of swordfish bone, mainly pieces of the swords, called rostra. Several rostra had been reworked into the same kinds of weapons we knew of from cemeteries, such as daggers, fish hooks, and even harpoons suited for swordfish hunting. Village sites do not contain the special artifacts found in cemeteries, but we did find more common kinds of tools that clearly linked this village site to the cemeteries.

All known cemeteries of the Red Paint People are tightly clustered along the Maine and New Brunswick coast. Image courtesy Bruce Bourque

All known cemeteries of the Red Paint People are tightly clustered along the Maine and New Brunswick coast. Image courtesy Bruce Bourque

Swordfish hunting is a big deal and not for the faint-hearted, for swordfish are among the fastest and perhaps the most dangerous fish in the ocean. Those found in the Gulf of Maine were huge, some topping 1,000 pounds. Feeding swordfish slash through schools of small fish or squid, but tire in the process, which allows them to be easily approached as they rest on the surface. Once struck by a harpoon, though, they often unleash their devastating power upon their assailants, darting away, then arcing back to drive their sword through even the thickest wood ship planking. Small boats like the dugouts used by the Red Paint People risked being overturned or even pierced by the sword, as happened to many Maine swordfishermen in the 19th century.

Spear tips or knives of beautifully translucent quartzite from Ramah Bay on the north coast of Labrador. Courtesy Bruce Bourque The archaeological evidence from the cemeteries and from sites like the Turner Farm tells us that the Red Paint People, unlike any other prehistoric coastal occupants, practiced a dangerous form of maritime hunting, and created large, complex cemeteries containing graves filled with beautiful and exotic artifacts. All this information left us wondering how this unusual hunter-gather culture could have emerged in a region where nothing else remotely like it had ever appeared.

Spear tips or knives of beautifully translucent quartzite from Ramah Bay on the north coast of Labrador. Courtesy Bruce Bourque The archaeological evidence from the cemeteries and from sites like the Turner Farm tells us that the Red Paint People, unlike any other prehistoric coastal occupants, practiced a dangerous form of maritime hunting, and created large, complex cemeteries containing graves filled with beautiful and exotic artifacts. All this information left us wondering how this unusual hunter-gather culture could have emerged in a region where nothing else remotely like it had ever appeared.

I approached the question by looking for clues from other cultures that hunted dangerous marine animals. Hunter-gatherer societies are generally quite egalitarian, but marine hunting usually requires hierarchically organized groups comprised of boat crews led by a high-status boat captain—a social entrepreneur who has amassed the material wealth and social skill needed to build a boat and command the loyalty of its crew. When not hunting, these men can use their boats for other self-aggrandizing purposes, such as to trade in distant places for valuable goods, or for warfare. Their high status also tends to garner them more wives and more children than commoners. They are both respected and feared.

There is another distinctive class of people, men usually, in hunter-gatherer societies, who act as intermediaries between their communities and the spiritual world that they alone are able recognize and enter. Anthropologists call such people shamans, and they, too, are both respected and feared. Shamans undertake spiritual or actual journeys to far-off places where the spirits dwell. They return with special knowledge or objects that gain their own potency, depending upon the difficulty of acquiring them from distant places, places like the Great Lakes and northern Labrador.

Yet another unusual thing about the Red Paint People is the discreteness of their territory, a small, well-defined area of the Maine and western New Brunswick coastal zone. No traces of their culture, for example, have been found even as close to the Androscoggin River as Casco Bay.

What this means archaeologically is that we have probably found nearly all the Red Paint cemeteries that exist and, while they are numerous, they are not numerous enough to have included all the souls who were a part of this culture over perhaps as much as a millennium.

Turner Farm today has been transformed into a thriving organic farm. The dig took place mostly in the area shown in the lower right side of this photo, near the beach and a marshy area. Photo by Bill Trevaskis

Turner Farm today has been transformed into a thriving organic farm. The dig took place mostly in the area shown in the lower right side of this photo, near the beach and a marshy area. Photo by Bill Trevaskis

If the cemeteries can’t account for the entire population, which portion of it was buried there? The artifacts provide a clue. They mainly include things like adzes and fishing weights, called plummets, that are associated with boats and fishing. They also include artifacts that we might expect shamans to have used in their rituals, such as the animal figurines, and the beautiful translucent spear points from Labrador—shamans were fond of translucent materials, as these evoke their special ability to see into and beyond objects. These two groupings of artifacts suggest to me that these cemeteries were for just boat captains and shamans.

What I suspect “explains” this remarkable culture is that, around 5,000 years ago, young male social entrepreneurs began to experiment with the dangerous sport of swordfish hunting, gaining great prestige by returning to their communities with this wonderful fish for all to enjoy. In evolutionary biological terms, they were demonstrating their prowess by “costly signaling,” that is by taking life-threatening risks to bring rewards to the community. These boat captains’ risk-taking was probably lessened by the spiritual protection provided by the shamans, and of course a man might have been both a boat captain and a shaman.

Radiocarbon dating tells us that the Red Paint People first appeared no earlier than 5,000 years ago and then suddenly vanished about 1,200 years later, replaced by a wave of immigrants from the southern Appalachians.

Small sculpted objects like these have often been found in Red Paint cemeteries, but rarely in village sites. They range in form from functional fishing weights to imaginary creatures. Courtesy Bruce Bourque

Small sculpted objects like these have often been found in Red Paint cemeteries, but rarely in village sites. They range in form from functional fishing weights to imaginary creatures. Courtesy Bruce Bourque

We do not know why or how they disappeared, but once again, their cultural uniqueness may provide a clue. Whatever the perceived communal benefits of swordfish hunting may have been, it made little sense in raw economic terms, for the loss of young men in their prime to swordfish hunting would have been costly, or maladaptive in ecological terms. The more sensible course would have been to ignore the swordfish and to focus upon the immense cod that lived in the same waters, and which could be caught with little effort or danger using only a hook and line. Both social stratification and economically maladaptive behaviors can place simple hunter-gatherer societies at risk, because their margin of survival is always thin.

The path chosen by the Red Paint People was probably exciting, but it may also have been their undoing, as such social arrangements tend to fall apart when they collide with the stubborn reality of the world.

Bruce Bourque is Senior Archaeologist, emeritus, at the Maine State Museum and Senior Lecturer in Anthropology, emeritus, at Bates College. His archaeological research focuses upon the Gulf of Maine coast.