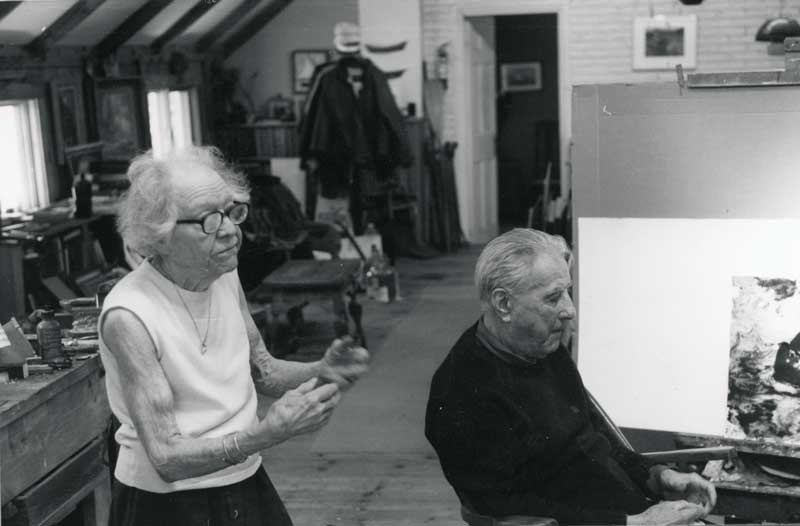

Helen and William Thon, shown here in their Port Clyde home in 1997, left $4 million to the Portland Museum of Art. Photo by Carl Little

Helen and William Thon, shown here in their Port Clyde home in 1997, left $4 million to the Portland Museum of Art. Photo by Carl Little

In 1997 I was part of a team of filmmakers who visited painter William Thon and his wife Helen at their home in Port Clyde. We were there to interview Thon for the Maine Masters video series. Certain details come to memory: the elderly couple welcoming us into their humble home, the unpretentious studio, the machine in the front hallway that enabled Thon, who suffered from macular degeneration, to read the newspaper. We were there to talk about the creative process and were treated to what can only be called a performance: Thon bringing into existence a stunning watercolor of a fishing boat in full fog.

After his death in 2000 (Helen had died the year before), the painter left $4 million to the Portland Museum of Art. He had a very successful career in art, selling many paintings, but the size of the gift was somehow astounding. The tradition of philanthropy in Maine is well known as are the names of the great benefactors—Baxter, Noyce, Rockefeller, Alfond, et al.—but who could have foreseen that this artist and his wife, who had lived such a modest life, would be the source of such a remarkable legacy?

Among Joseph Fiore’s most important work was a series of paintings portraying abstracted rocks, including Virgo Tiger, oil on canvas, 1986, 38" x 48". Courtesy Maine Farmland Trust, photo Falcon Foundation/David Dewey

Among Joseph Fiore’s most important work was a series of paintings portraying abstracted rocks, including Virgo Tiger, oil on canvas, 1986, 38" x 48". Courtesy Maine Farmland Trust, photo Falcon Foundation/David Dewey

The bequest was designated to support the Portland Museum of Art’s biennial, a showcase of contemporary artists connected to Maine. The most recent edition, curated by Alison Ferris in 2015, for the first time ever featured objects made by Native American Maine artists. Theresa Secord, Sarah Sockebeson, George Neptune, and Jeremy Frey joined the likes of Lois Dodd, John Bisbee, Emily Nelligan, and John Walker. It felt like a kind of cultural ceiling had been broken. Thon would have loved it.

He is among a handful of Maine artists in the past three decades whose artistic legacies include funding and promotion for future artists. It’s a classic example of paying it forward. In addition to young artists, the beneficiaries include all art lovers in Maine.

Not far inland from Port Clyde, in Jefferson, Joseph Fiore was painting the Maine landscape with equal passion. Where Thon had specialized in seascapes, Fiore (1925-2008) preferred the countryside: farms, trees, meadows. Fiore, too, had the future in mind when he planned his estate: he provided an endowment for the preservation and display of his work and that of other Maine artists at the Firehouse Center in Damariscotta. His legacy has been further enhanced by the creation of the Joseph Fiore Art Center in Jefferson on a property owned by Maine Farmland Trust (MFT). The idea for an artist-in-residence program there was hatched by David Dewey and Rob Gregory, trustees for the Falcon Foundation, and MFT’s John Piotti and Anna Abaldo.

Now in its second summer, the residency at Rolling Acres Farm is managed by the trust. Fiore admired MFT’s mission to preserve farms and wanted to further support its work. The trust received a substantial gift of his work, which it has been selling but also donating to nonprofits. The latter effort has led to the creation of the Fiore Art Trail comprising 50 organizations that have acquired his work. The list is diverse, ranging from many land trusts and several colleges (Bates, Colby, College of the Atlantic, Unity) to the Maine Cancer Foundation and the Maine Association of Nonprofits.

Bernard “Blackie” Langlais’s Bear Group, restored by the Kohler Foundation, is on view at the sculptor’s former home in Cushing. Photo courtesy Georges River Land TrustSpeaking of trails, in 2014 the Colby College Museum of Art in partnership with the Kohler Foundation launched the Bernard Langlais Art Trail. The trail grew out of the bequest of the Langlais estate by the artist’s wife, Helen, to Colby in 2010. After acquiring 180 works for its collection, the Colby Museum gave nearly 3,000 works to the Wisconsin-based Kohler Foundation to preserve and distribute.

Bernard “Blackie” Langlais’s Bear Group, restored by the Kohler Foundation, is on view at the sculptor’s former home in Cushing. Photo courtesy Georges River Land TrustSpeaking of trails, in 2014 the Colby College Museum of Art in partnership with the Kohler Foundation launched the Bernard Langlais Art Trail. The trail grew out of the bequest of the Langlais estate by the artist’s wife, Helen, to Colby in 2010. After acquiring 180 works for its collection, the Colby Museum gave nearly 3,000 works to the Wisconsin-based Kohler Foundation to preserve and distribute.

The foundation has found homes for Langlais’s drawings, paintings, and sculptural works with more than 50 nonprofits. The trail stretches from Waterfall Arts in Belfast to the Monhegan Memorial Library, from the Ogunquit Museum to the Solon Town Office, from the Cushing Historical Society to the Lincoln Theater in Damariscotta. Helen Langlais’s bequest included the couple’s 90-acre property in Cushing, part of which her husband had transformed into a kind of sculpture park. In 2014 the Kohler Foundation turned it over to the Georges River Land Trust to manage. This fall, the trust will open it to the public as the Bernard Langlais Sculpture Preserve.

On Great Cranberry Island, the Heliker-LaHotan Foundation is marking its 23rd season of residencies for artists from Maine and far beyond. The foundation is the gift of the painters John Heliker (1909-2000) and Robert LaHotan (1927-2002), who purchased the home of Captain Enoch B. Stanley in 1958 and spent every summer there painting.

To date, the foundation has hosted more than 100 artists and organized numerous projects and public events on the island. The residency provides board and lodging. Residents have included Joellyn Duesberry, Judy Taylor, Holly Meade, Siri Beckman, Philip Frey, and Nina Jerome.

Beverly Hallam in her York, Maine, studio in 2010 during the filming of the Maine Masters documentary. Photo by Carl Little

Beverly Hallam in her York, Maine, studio in 2010 during the filming of the Maine Masters documentary. Photo by Carl Little

This summer for the first time the foundation is offering plein air workshops in July followed by residencies in August and September. Two Maine-based artists are in the mix: Priscilla Stevens of East Winthrop and Jessyca Broekman of Brunswick. The program also hosts several visiting artists over the summer and fall.

An example of a legacy in the making is the Surf Point Foundation established by painter Beverly Hallam (1923-2013) and her long-time companion, collector and art patron Mary-Leigh Smart (1917-2017). Their 41-acre oceanfront estate on the coast of York will become an artist residency next spring, with the goal of having a half dozen or so artists on site through fall 2018.

My last example of an artist’s legacy is personal. When my uncle, the painter William Kienbusch died in 1980, he left his house and studio on Great Cranberry Island to my brother David and me. Uncle Bill felt that his nephews should have a place to go to paint and write poetry—a most generous and thoughtful gift that keeps on nurturing our creative endeavors.

In the first decades of the new century, artists and their families are creating new opportunities for artists who might not otherwise afford to spend time in Maine. Paying it forward and giving back are both clichés of philanthropic action, but for good reason: these individuals have chosen to share their good fortune with future generations. That’s the art of leaving a legacy.

Carl Little’s most recent book is Philip Barter: Forever Maine (Marshall Wilkes).