“Let’s build that one.” Thus spoke my 12-year-old son, peering over my shoulder as I explained I was looking for a boat to build. He was unconstrained by the logic of an adult mind, and at a glance he selected the most beautiful of all small wooden boats, the Haven 12½. I wish all of my life’s most important decisions were so easily made.

It took them eight years, but C. Daniel Smith and his sons built this Haven 12½, aptly named Legacy, all by themselves, learning technical skills and strengthening family bonds along the way. Left to right: Michael, Daniel, and Nicholas. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

It took them eight years, but C. Daniel Smith and his sons built this Haven 12½, aptly named Legacy, all by themselves, learning technical skills and strengthening family bonds along the way. Left to right: Michael, Daniel, and Nicholas. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

My background would hardly suggest that someday I’d find myself entertaining such a project. I grew up in central Missouri, and my only formal woodworking training was junior high school shop, a class I nearly failed. We were a rebellious group of preteens with an unhappy teacher, supplied with dull coping saws and given the command to build a gun rack. When I grew tired of gnawing at the oak boards I’d steal a glance at our teacher running beautiful sheets of plywood through a table saw as he built cabinets for his home. If we pleaded, the teacher would reluctantly run our boards through the bandsaw, and grimly hand back perfection. I was fascinated by the raw power of this machinery and vowed one day to become proficient in the use of these magical power tools.

My junior year in high school, I became entranced by an article describing how to build a grandfather clock. I begged the shop teacher to let me work in the shop instead of sitting in study hall, and somewhat surprisingly he acquiesced. A testimony to raw ambition and youthful ignorance, this clock later won a grand prize in our state woodworking contest. I was forever hooked. From coffee tables to beds, bookcases to fireplace mantels, I found immense satisfaction in the process of creating.

My introduction to boatbuilding was nearly as improbable. My father and I were spending a long weekend in a faraway city where I was seeking treatment for his terminal cancer. He’d lost his eyesight, so at his request I read aloud to him an article on building a cedar-strip canoe. When I finished, he suggested I should build one.

The process was a transition from the normal security of the framing square and the hard angles of

cabinetry. I learned about strongbacks and sheerlines, and about learning to trust my eyes and hands to develop the gentle curve of a hull. The setup may be squared and trued, but the development of a complex curve is the aesthetic perfection that becomes a boat. My two sons were toddlers, but they were exposed to the process. And it was therapy for me as I dealt with my father’s eventual passing.

As the boys grew, they learned the value of working in tandem, hand planing over 600' of western red cedar. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

As the boys grew, they learned the value of working in tandem, hand planing over 600' of western red cedar. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

My sons were growing and I felt the need to expose them to my love of woodworking. The more I read about the Haven, the more I came to realize it was the perfect boat to build. The wizard of Bristol, Nathanael Herreshoff, first built a full-keel version in 1914. Carvel planked and built upside down with a mold for each frame, the 12½ was meant as an instructional beginner’s boat for boys, but the design proved so popular it became the most widely built boat in the Herreshoff shop—350 were built by 1943. Venerable versions exist today, lovingly maintained and raced by passionate owners throughout New England waters.

In 1985, the late Joel White of Brooklin, Maine, took the lines of the original design and created a centerboard version, making it trailerable and arguably more maneuverable. Naming it the Haven 12½, he published a manual on how to build the boat, along with the plans. In a glance, my older son had picked the ideal boat for us to build, though we’d never sailed aboard one, nor even seen one in person.

My cedar-strip canoe had been built in the garage, and I learned how frustrating it was to walk endless circles around the project in a tight space searching for a tool that was inevitably lost on the opposing side. I needed more space, so I first built a new shop large enough to hold this boat, arranging paper cutouts of the stationary tools and hull shape in various configurations before settling on a design for the space. The doors had to be wide enough to get the boat out of the shop eventually. Little did I know then how close that would be! Cabinetry was built and tools were sharpened. After I gave her the first tour of the new shop, my mother, who rarely saved anything, wryly handed me the report card from my misspent youth, peppered with “Inferior” and “Unsatisfactory” marks from the junior high instructor of Industrial Arts. At first I wanted to conceal it from my sons, but after some reflection, I had it laminated instead. It’s proudly displayed in my shop today.

Although a 16-foot boat (the Haven’s overall length) seems small by yachting standards, it’s a big project for a small boatshop. We spent a year building molds and steaming frames before we could even begin to connect the mahogany transom to the keel to the stem. Planks were nearly 20' long, each bandsawed and hand planed from western red cedar, wrestled into place and secured with bronze screws. The rhythmic repetitiveness was satisfying. At first the boys would help me independently, but as they grew, they became complimentary of one another’s skills and began working together. Each became proficient at hand planing to within a whisker of a drawn line, at the precise bevel necessary to produce a tight-fitting plank.

Some days we’d be too tired or the hour too late to work, so we’d study the emerging shape of the hull and plan our next steps instead, sometimes simply admiring what we’d done. Other days we’d lose ourselves in the work and the solace of music or a ball game playing on the radio. At last the hull was completed. A temporary overhead pulley system was rigged and we hoisted the boat. At first it seemed as if nothing would happen, but slowly the boat broke free from the molds and in a heartbeat spun over. The upright boat filled the shop as it nestled into the newly made cradle. We vowed we’d never see her upside down again! Four years had passed.

Work continued more or less steadily, but as the boys went off to college, I was slowed by the lack of an assistant. When they came home for holidays we’d catch up for a bit about their college lives, and then we’d head out to the shop and fall into our routine. Sometimes we’d argue, but mostly I remember the times we laughed and joked or solved problems as a team. Eventually the interior was completed, the spars made, and the keel, rudder, and tiller attached. Bronze hardware was installed. There was nothing that could be done any longer inside the shop. Eight years had passed.

Here is the rewarding first view of the inside of the boat on a seminal day. The boat was lifted and turned after four years of work. They were half done. Their first boat, a canoe, hangs from the ceiling in the background. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

Here is the rewarding first view of the inside of the boat on a seminal day. The boat was lifted and turned after four years of work. They were half done. Their first boat, a canoe, hangs from the ceiling in the background. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

Out of the shop we were, at last, able to see the boat from a distance and admire the beauty of this design. The mast was stepped and the standing and running rigging completed. I had trouble sleeping that first night, knowing how lovingly we had painted the hull and varnished the mahogany transom. Illogically I worried the boat might get wet if it rained! A wonderful christening party was held with friends, family, live music, and speeches. That evening, long after midnight, my wife Robin and my two sons and I crawled inside the spacious cockpit, opened a bottle of champagne and toasted our accomplishment. We’d had an adventure already, but so much more was to come.

My older son’s girlfriend Kailee helped us launch the boat in a local lake the next morning. A little wobbly at first, we became more comfortable as we grew accustomed to the tiller and gaff-rigged design. The five of us felt comfortable and secure on that maiden sail. The boat was loaded up in a truck and we struck out on a cross-country trip to Maine, where she now resides in Islesboro, lovingly sailed each summer, and stored in my woodshop in the winter.

Satisfaction in building a wooden boat must come from accepting that it is a temporary endeavor. As soon as the boat leaves the shop it’s subjected to the harsh realities of the sun and water. Inevitably it will rot and decay, and someday it’ll no longer be sailable. Much like life itself, there’s a quixotic nature to the art of boatbuilding, only slightly less foolish than the work of the sidewalk artist who’s at the mercy of the next rain.

So what is the permanence of this? What did we gain and lose by building a boat? As I reflect, I can recall missing nothing but some television over these years. Both boys played sports through high school and became Eagle Scouts. We didn’t miss a single one of their events during this time.

Dan Smith’s sons, now more men than boys, on their first sail in Maine in Gilkey Harbor, Islesboro. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

Dan Smith’s sons, now more men than boys, on their first sail in Maine in Gilkey Harbor, Islesboro. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

My older son was asked about his hobbies during medical school interviews and his interrogators would stop cold when he said he built a wooden boat. In Missouri. He has married his high school sweetheart and is now in the fourth year of a residency in orthopedic surgery at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, New Hampshire. He’s just about to turn over the 18' cedar-strip rowing scull he’s been building in his spare minutes in his garage.

My younger son, who now works and lives in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering. He’s become the sailor I’ve always wanted to be, having just finished restoring a 16' Hobie Cat and sailing it solo nearly 30 miles around the Isles of Shoals. This past summer I was honored that he and his new bride Emily chose to marry in my woodshop in Maine.

Hence the name Legacy. We can shower our children with gadgets that last as long as the batteries remain charged, or we can take the more difficult path of instilling a sense of pride and accomplishment that comes with creating an object of indescribable beauty. I still feel a hint of separation anxiety when I first leave Legacy on her mooring each summer in Gilkey Harbor, but I’m learning to accept the fact that boats, like children, are meant to be molded into the best shape possible, and then cherished for what they’ve become, trusting that they’ll continue to remain afloat.

When I met Steve White, the owner of the Brooklin Boat Yard and son of the late Joel White, at his yard in Maine, I expressed the debt of gratitude I owed Steve’s father for putting this boat within the reach of so many amateur builders. He replied that it wasn’t an easy boat to build, but if a person could build it he could build any boat in the harbor. I looked from his office at some of the prettiest boats I’ve ever seen afloat and thanked him for the compliment.

I know I don’t have the skills these men possess. I will, however, continue to try.

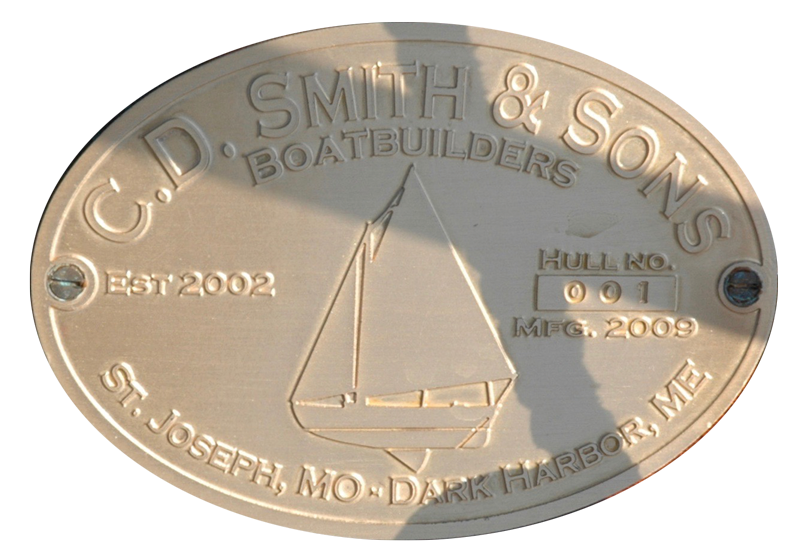

The vessel has its own special builder’s plate. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

The vessel has its own special builder’s plate. Photo courtesy C. Daniel Smith

C. Daniel Smith is an orthopedic surgeon in St. Joseph, Missouri. He summers on Islesboro, and when not sailing Legacy, he’s at work in his island shop or aboard his Concordia yawl, Eagle.