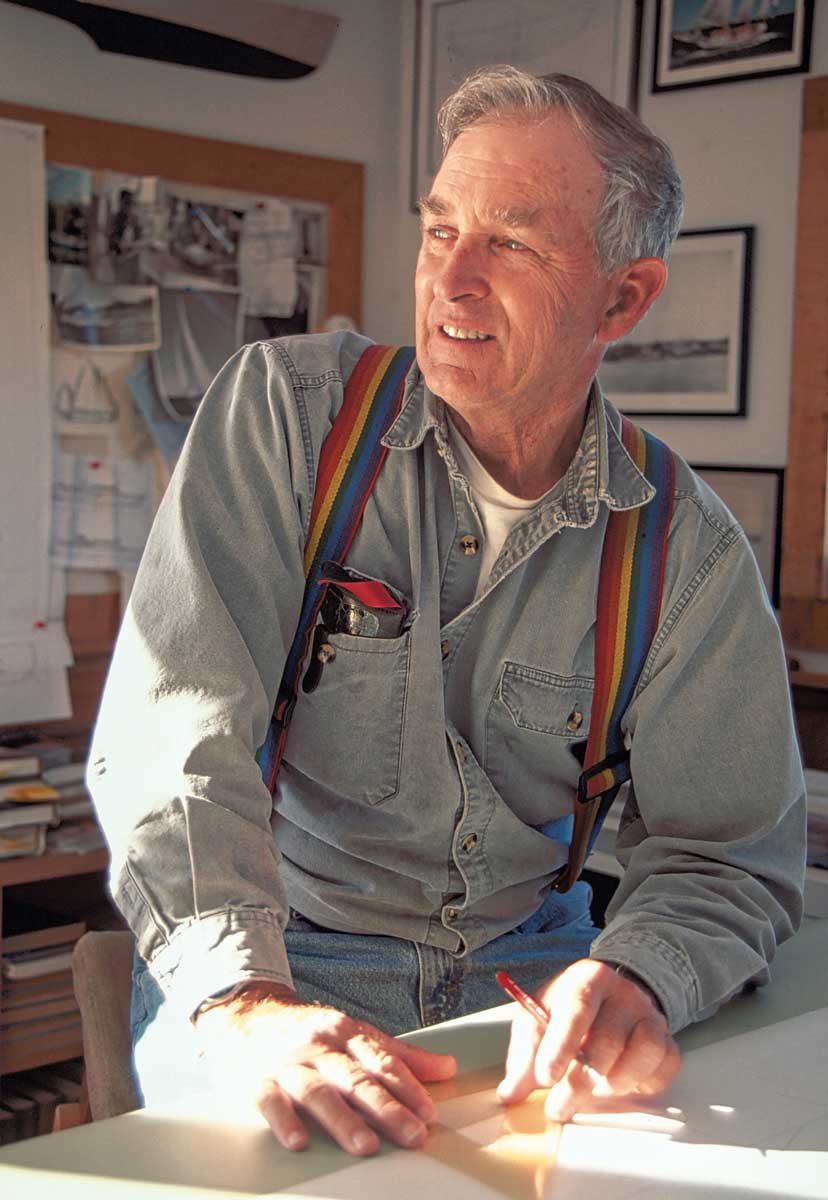

Joel White in his design office. Note that his pencil has no eraser. He drew fast and he usually got it right the first time. Photo by Billy BlackI keep a couple of boats moored in Center Harbor in Brooklin, Maine, and am in and out of there several times a day from May through October. Among the pleasures of these comings and goings is the chance to pass by boats that Joel White designed, and in most cases built, at his Brooklin Boat Yard.

Joel White in his design office. Note that his pencil has no eraser. He drew fast and he usually got it right the first time. Photo by Billy BlackI keep a couple of boats moored in Center Harbor in Brooklin, Maine, and am in and out of there several times a day from May through October. Among the pleasures of these comings and goings is the chance to pass by boats that Joel White designed, and in most cases built, at his Brooklin Boat Yard.

In a harbor filled with notable classics, Joel’s designs stand out for their steadfast beauty and clarity of purpose. In almost every category, from dinghy through fully tricked-out sailing yacht, each seems to be at home; the right boat for the right place.

In these turbulent times when so much of what we have known appears uncertain, I find myself looking for heroes who have managed to hold firm, no matter what. Joel White (1930-1997) was surely one of these. He was steadfast, focused, and a generous-spirited friend to many. As the son of the writer E.B. White, he was also something of a cultural hybrid in downeast Maine, especially in his early years, when a man with a degree from M.I.T. in naval architecture doing blue-collar boatbuilding work was an anomaly.

Joel started on his way when he was nine years old and his parents up-staked from Manhattan and moved to a farm in North Brooklin. He roamed the fields and woodlands and explored the beginnings of a saltwater life along the shore of Allen Cove and then farther out into Blue Hill Bay.

Joel kept busy. One spring he raised a baby crow, pretty much a full-time job. One winter he built a little scow with his father and rowed it on their pasture pond come spring. He went lobstering with the fisherman from down the road, caught flounder from a rowboat in the cove, worked in his dad’s wood shop, and learned to sail, mostly on his own, in a Herreshoff 12½ when he was 16. Over the stages of his young life, he came to understand exactly who he was, what he wanted to do, and where he wanted to do it—to be a boatbuilder in Brooklin, Maine. It was upon this ledge that he constructed a life.

Years later when my wife Caroline and I sailed with him aboard his Augie Nielson-designed Danish-built double-ended cutter, Northern Crown, he taught us the art of cruising: simple food, a dinghy that is fun to row and sail, good books and good chowders, and an anchor that stays where you put it, and much more.

Whether we were joined by his daughter, Martha White, or future son-in-law Taylor Allen, or maritime historian and boatbuilder Maynard Bray and his wife Anne, all agreed that by mid-summer we wanted to sail east to the remotest sections of Maine, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. To anchor off wild islands and scramble up their windswept heights. To seek out colonies of razorbills, guillemots, puffins, terns, and petrels. To spend time on Grand Manan Island, where fishermen still tended weirs in the old way.

We also wanted to sail among as many wooden boats as possible. In those days, Beals Island-built lobsterboats were everywhere along the Maine coast. Farther east, high-bowed Novi boats dominated. Anchored at night off a reach or thorofare, we would regularly awaken to hear herring seiners and sardiners pounding by on their way to canneries in Stonington, Rockland, Prospect Harbor, or Blacks Harbour in New Brunswick.

In those days, if you went far enough east, you could occasionally see men hauling traps out of peapods or hand-lining for cod. Salt fish was everywhere, hanging to dry from clotheslines out back, nailed to the fish house wall for a quick snack, or stacked on docks by the pallet-load ready for shipment to the Caribbean. In something close to 20 summer cruises, the economics and skills of along-shore fisheries in all their ancient particulars never lost their fascination for Joel.

Back home at the boatyard, as demand for his designs grew, the boats Joel drew and built reflected the linear simplicity and structural integrity of the workboats and yachts we’d sailed among. That these elements appeared in his designs was no accident. By that time, they were hardwired into his consciousness.

Some years later, in the regular column he wrote for WoodenBoat magazine he observed, “Just as a painting is influenced by the artist’s environment and early training, so is the naval architect’s design affected by the area in which he lives and the local traditions of boatbuilding.” In a subsequent column, he described his theory that the best yacht designers instill some of their character traits into their designs.

As examples, he cited Nat Herreshoff, “work-a-holic, a demon for speed, (who) turned out a huge body of work, meticulously designed and crafted, fast and long lived;” Nat’s son, L. Francis, a lover of beauty and simplicity whose yachts were beautiful and simple; and John Alden, a racer and deep-water sailor who “took the fisherman-type schooner and modified the design into offshore yachts that were simple, strong, and economically appealing to the yachtsmen of the Depression years.”

And so it was to be with Joel, his work flowing from the total immersion he lived so deeply along the coast.

When it came right down to it, however, Joel would never talk about himself this way. He was too self-effacing for that. Sure, he might analyze the work of others and draw some conclusions, but he was never the type to spend time staring into his own oeuvre. If someone asked about his designs, hoping to come up with some over-arching summary statement, he’d most likely dismiss the question with one of those self-deprecating chuckles he specialized in, saying something like, “Mostly my designs just walked through the door with customers and then I tried to do the best I could for what they wanted.”

Because he would let his designs speak for themselves, let’s look at a few favorites.

One of these is surely the Bridges Point 24. Joel always said it was harder to design a good-looking small boat than it was a large one. Accordingly, when called upon to design a small sloop for local boatbuilder Wade Dow, he went all the way back to the well-loved Herreshoff 12½, his first command as a boy, for inspiration.

The result was a handsome and versatile sloop, just right for the Maine coast. Quick around the buoys, sturdy in a two-foot chop, small enough to singlehand yet big enough for overnights, the Bridges Point is on almost any sailor’s list as their “next boat.”

Sweet Olive materializes out of the fog. A plank-on-frame sloop built 33 years ago, she still looks brand new even on a sunny day. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Sweet Olive materializes out of the fog. A plank-on-frame sloop built 33 years ago, she still looks brand new even on a sunny day. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Another favorite is the 43' sloop, Sweet Olive. Built for a repeat customer who deeply valued the time Joel took to develop his ideas for a boat, the result reflected all White had learned to value in a cruising sailboat capable of offshore passages.

Grace goes to windward in a breeze. With much of the beauty of L. Francis Herreshoff’s Quiet Tune, she features the sort of modern underbody that soon became known as a “spirit of tradition” design. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Grace goes to windward in a breeze. With much of the beauty of L. Francis Herreshoff’s Quiet Tune, she features the sort of modern underbody that soon became known as a “spirit of tradition” design. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

Right next to my mooring is the ketch-rigged Center Harbor 31, Grace. Strongly influenced by L. Francis Herreshoff’s masterpiece, Quiet Tune, she sails the waters of the Eggemoggin Reach with her own special blend of simple elegance.

Last on the list is the lobsteryacht Woody, called Lady Jean when it was launched. Transforming a classic lobsterboat design into a successful pleasure boat is no easy task, but Joel managed it perfectly here: forthright, purposeful, but gracefully stretched-out enough to make it beautiful. Even lobstermen nod approvingly when Woody chugs by.

Sometimes sailing through the harbor, I just see Joel’s boats. But often as a particular model comes into view, I hear his voice as well. Joel spoke of boat design and the uses of boats vividly and with particular astuteness. That I can hear his words so clearly still, nearly 20 years after his passing, is beyond describing.

Bill Mayher lives in Brooklin, Maine, and is one of the founders of the maritime web site offcenterharbor.com.