Fishing for landlocked salmon in Grand Lake Stream, one of four freshwater salmon populations that date to the end of the last Ice Age. Photo by C. Schmitt

Fishing for landlocked salmon in Grand Lake Stream, one of four freshwater salmon populations that date to the end of the last Ice Age. Photo by C. Schmitt

Arctic char, such as this one, prefer cold water at the bottom of deep lakes. Photo courtesy Bangor Water District Maine lakes are home to two evolutionary wonders of the animal kingdom, Arctic char and landlocked salmon, related species of fish that exist in very few places.

Arctic char, such as this one, prefer cold water at the bottom of deep lakes. Photo courtesy Bangor Water District Maine lakes are home to two evolutionary wonders of the animal kingdom, Arctic char and landlocked salmon, related species of fish that exist in very few places.

They descend from a common ancestor that lived millions of years ago. Evolution took them on diverging pathways during repeated ice ages. The char stayed farther north, swimming in pools of meltwater along the edges of ice sheets, navigating unstable landscapes of loose rock, sediment, water, ice. Growing glaciers pushed char uphill on a wave of water, or forced them to the icy margins.

The salmon took to the sea, south of the ice, finding open rivers in which to spawn.

SEBAGO LAKE SALMON

SEBAGO LAKE SALMON

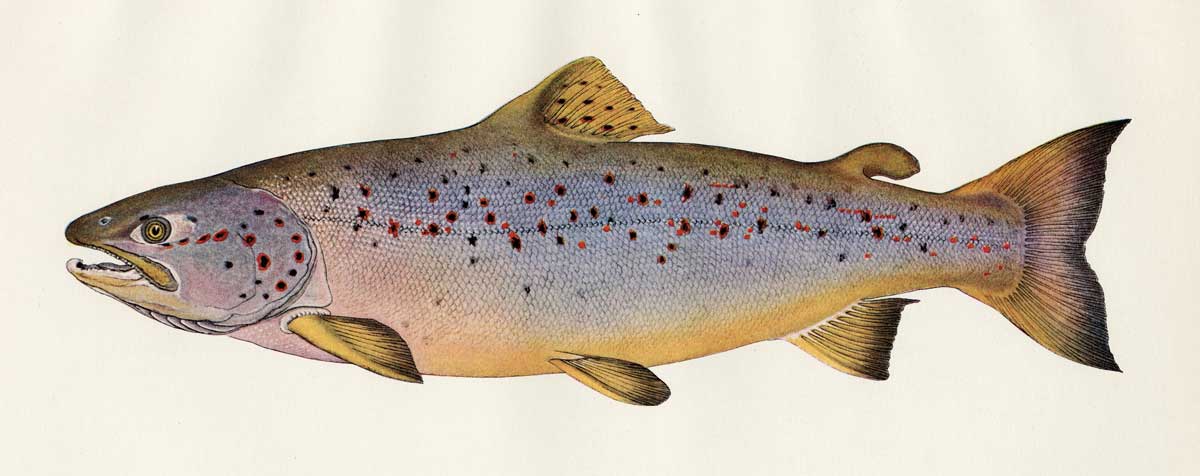

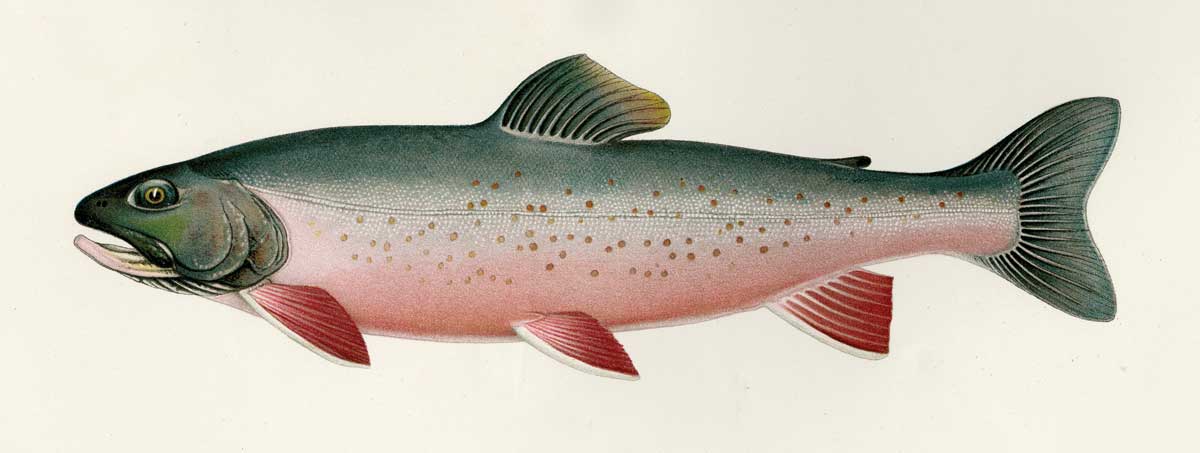

ILLUSTRATIONS: These early twentieth-century images of landlocked salmon from Sebago (above) and from Grand Lake Stream (below) show how lake-specific fish evolved differently. These illustrations by W. H. Rich are from The Fishes of New England by William Converse Kendall, published in 1935 by the Boston Society of Natural History. Landlocked salmon are the Maine State Fish; char are the State Heritage Fish. Illustrations courtesy University of Maine Raymond H. Folger Library (3)

GRAND LAKE STREAM SALMON

GRAND LAKE STREAM SALMON

Both fish found their way into the place that became Maine sometime at the end of the last ice age, 10,000-15,000 years ago. They have been here ever since.

Having a closer affinity for icy conditions, char likely would have arrived first, into Floods Pond and Green Lake in what today is Hancock County. As the ice continued to melt, the char followed, flourishing in the freshly exposed habitat.

RAINBOW LAKE ARCTIC CHAR

RAINBOW LAKE ARCTIC CHAR

Char and salmon are relics, a surviving trace of Maine’s glacial history. Their presence reveals something about how physical forces shaped our homescape.

The mile-deep Laurentide ice sheet that once covered Maine did not melt at a steady rate, although it did recede in a consistently northwesterly direction. Geologists have described irregular shifts and ripples that occurred in the land surface after the glacier disappeared. Meanwhile, rivers roared through the exposed earth, sands shifted, lakes filled and emptied, and it was cold everywhere.

Enter the char, the world’s northernmost freshwater fish, found in lakes throughout the arctic and subarctic. In the lower 48 they persist in just 12 cold, deep lakes in the headwaters of the St. John, the Union, and the Penobscot watersheds. Two additional lakes have char as a result of stocking by the state of Maine. According to Maine Dept. of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife biologists, char live a long time—up to 15 years. They can grow to be about 20" long, but most are much smaller. They are similar to salmon or trout in appearance, but slimmer. Salvelinus alpinus has been designated the Maine State Heritage Fish.

Separated for thousands of years in separate water bodies, Maine char evolved unique characteristics, with fish from different lakes showing great variability in size, color, shape, and spawning behavior. There are “dwarf char” in Green Lake that prefer deep water, and big char in Wadleigh Pond that like the shallows. There’s the “Sunapee trout” of Floods Pond, the small silver char of Wassataquoik Lake, and the orange-finned char of Big Black Pond. Char are often called “blueback trout,” although some are spotted black.

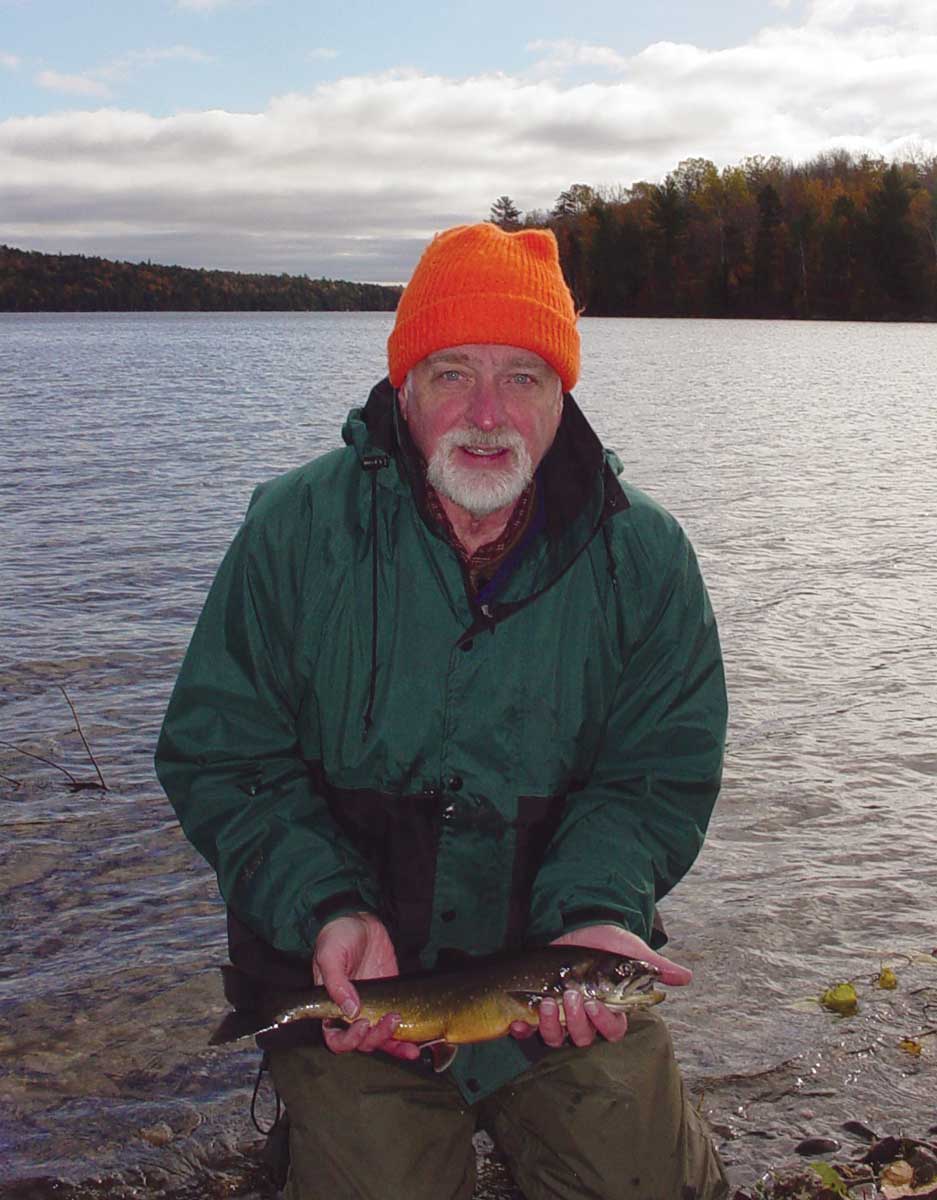

The Bangor Water District works with University of Maine researchers to monitor the population of char, such as this one, in Floods Pond. Photo courtesy Bangor Water District

The Bangor Water District works with University of Maine researchers to monitor the population of char, such as this one, in Floods Pond. Photo courtesy Bangor Water District

Recent genetic analysis has shown that while all the char in Maine originated from a common ancestor, the different populations are now genetically distinct from each other and from populations in nearby Canada.

Char are flexible. However, because they adapted to live in cold and nutrient-poor environments, free from predators and competitors, they can’t tolerate warm temperatures nor do they like to share space with other fish. They are used to being the first and the only. The Rangeley Lakes lost their char a century ago after introductions of rainbow smelt and landlocked salmon. In Big Reed Pond, north of Baxter State Park, the introduction of rainbow smelt nearly wiped out the char; fishery managers “reclaimed” the pond by rescuing the char and holding them temporarily at a hatchery while dosing the lake with organic chemicals to kill the smelt. The char were returned but the jury is still out on whether the process worked. Meanwhile, smelt have appeared in two other char habitats. The char of Green Lake co-evolved with smelt and salmon, so they may survive yet, as long as the water doesn’t get too warm too fast.

Like the char, Atlantic salmon expanded their range as the glaciers melted and rivers and cold lakes developed. Were they stranded in place as the land tilted and drained? Or did they gradually adapt to life in lakes? Whether sudden or slow, Atlantic salmon established persistent lake-based populations in four bodies of water: Sebago, Green, Sebec, and West Grand lakes. Fishery managers have since spread them around, so that landlocked salmon can now be found in around 300 lakes and reservoirs, where they support major angling activity. Grand Lake Stream, the East Outlet of Moosehead Lake, and the West Branch of the Penobscot River are world-famous for salmon fly-fishing.

Landlocked salmon have been called Schoodic trout, lake shiner, salmon trout, and black-spotted trout. Native Americans know them as ouananiche. They leave their lakes and enter tributary streams for spawning.

University of Maine researcher Wesley Wright holds an Arctic char from Floods Pond, a cold, deep lake that also supplies high-quality drinking water to the City of Bangor. Photo courtesy Bangor Water DistrictDavid Boucher, a regional fisheries biologist with IFW, described classical salmon habitat as a “large, deep, clear lake with rocky shores, cool well-oxygenated water in its depths, an abundance of smelts, and fed by a swiftly flowing stream with a gravelly bottom.” Maine’s best salmon fisheries occur in lakes with large volumes of deep water that remain colder than 50°F during the critical summer period and where dissolved oxygen levels remain above eight parts per million, he added. “Our best wild fisheries are in lakes that have large inlet or outlet streams with abundant spawning and rearing habitat. Recent studies in Maine show most salmon (about 75 percent) spend two years as stream dwellers.”

University of Maine researcher Wesley Wright holds an Arctic char from Floods Pond, a cold, deep lake that also supplies high-quality drinking water to the City of Bangor. Photo courtesy Bangor Water DistrictDavid Boucher, a regional fisheries biologist with IFW, described classical salmon habitat as a “large, deep, clear lake with rocky shores, cool well-oxygenated water in its depths, an abundance of smelts, and fed by a swiftly flowing stream with a gravelly bottom.” Maine’s best salmon fisheries occur in lakes with large volumes of deep water that remain colder than 50°F during the critical summer period and where dissolved oxygen levels remain above eight parts per million, he added. “Our best wild fisheries are in lakes that have large inlet or outlet streams with abundant spawning and rearing habitat. Recent studies in Maine show most salmon (about 75 percent) spend two years as stream dwellers.”

Salmon are more competitive than char: they prey on smelt and co-exist with native brook trout, although they don’t get along as well with non-native smallmouth bass and northern pike. Warming temperatures are also a threat.

Char, in their diversity of forms, and salmon, in their freshwater habits, have shown that evolution continues into contemporary times, sometimes quite rapidly. Both species are at the southern edge of their range, making their unique genetic adaptability all the more important, because flexibility may be the most important trait in a world where the environment is changing fast.

Biologists urge conservation of the fish in every lake where they occur. These fish with their ancient but evolving DNA are a glacial inheritance. Their cells and the molecules of the landscape that surrounds them hold untold fortunes worth protecting.

Photo by E. GreenCatherine Schmitt is the author of The President’s Salmon: Restoring the King of Fish and Its Home Waters, published in 2015 by Down East Books.

Photo by E. GreenCatherine Schmitt is the author of The President’s Salmon: Restoring the King of Fish and Its Home Waters, published in 2015 by Down East Books.