Illustration by Caroline MagerlThe ledges of Mackerel Cove, draped in kelp and bristling with barnacles, look today much as they did back in the 1930s when my summer friends Dick, Del, and I raced our punts around the cove’s bights and promontories. Here in this place of abidingness I am often caught up in a friendly warp of time.

Illustration by Caroline MagerlThe ledges of Mackerel Cove, draped in kelp and bristling with barnacles, look today much as they did back in the 1930s when my summer friends Dick, Del, and I raced our punts around the cove’s bights and promontories. Here in this place of abidingness I am often caught up in a friendly warp of time.

The Cove was our summer playground. We rowed on it, waded in it, and fished in it. We hunted starfish and crabs among its rocks, scooped sand dollars from its shallows, and ruffled its reflections with our oars.

From the high ground of native pride, Dick and Del missed no opportunity to impress me with the splendid superiority of their island ways. In me they found an eager recruit; they abetted my schemes to become an islander like them, to spend the winter here, forsaking family to prolong this summer fellowship. I sometimes forgot that the school-bell also tolled for them, and Labor Day ended this time of life for us all.

Unlike others our age, we shared the loose kinship of being fatherless—I for the summer, Dick and Del more or less permanently. Our idle pursuits marked us as pretty useless in the eyes of island grown-ups; loafing might be okay for summer kids, but fatherless Dick and Del were clearly bound for mischief.

For Dick Bixby and Del Richardson, the parental thing was subtly defining. Del had no visible parents. He lived with his Nana in a weathered clapboard shack on Summer Hill, where a rooster wandered the cluttered kitchen as familiarly as a pet cat. For want of a nuclear family, perhaps, Del had a reputation as a “bad boy,” for which I never saw any evidence. He wore a wide grin and called himself “Del the Pirate,” stealing distinction from any low esteem. For me, he was a most enviable of free spirits, an island Huck Finn who did what he wanted.

Dick, on the other hand, boasted noble island ancestry on his mother’s side. Blonde, harried Margaret Sinnett Bixby, who put in long days waitressing at the Woodbine Inn, could claim aristocratic descent from the first Sinnett who escaped impressment from a British man-of-war and settled here in the late 18th century. Dick’s father, the missing Bixby, was an absentee Army officer whose whereabouts went unmentioned.

Dick was my most constant companion. He turned up whenever he had an adventure that needed company or complicity. We disagreed regularly on matters we could never quite remember, then renewed our friendship as though it had no past. We’d set off to comb Pebbly Beach for flint and chalk, or check the apples in Skidmore’s orchard for their ripeness, or maybe decide to pester the crows in the thick spruce groves at the North End. Sometimes we set ourselves the grandest of all challenges: to circum-walk the island following the shoreline north or south. Somehow we never went farther north than Robin Hood Beach nor more southerly than Little Harbor before some other more enticing and less strenuous adventure took us inland. It was just as well. There are parts of the coast near Water Cove we never saw, terra incognita from which we might never have returned. Some shores are better left unknown.

If the day dawned sullen, we’d go fishing down at Bass Rock wharf. Myth has it that fish, perhaps lured by the dimples of raindrops, rise to the surface on rainy days, their mouths agape and their minds more easily persuaded to take the hook. Bait debates preceded these excursions. Snails were the poor boy’s bait, found everywhere. Their gristle had the virtue of hooked-on toughness, resisting vigorous nibbles though seldom inviting a solid strike. Brim was better regarded for its smelliness, but we had to ask for it or “borrow” from some lobstermen’s bait barrel. Dick, because he was half islander, was our forager-beggar on these occasions.

Back in those days before bottle recycling, we might spend whole mornings on the beach busting them. The shards of our efforts, worn smooth and small by countless tides, glint jewel-like in the sand today, their cloudy blues, whites, and ambers a treasure gathered by grandchildren. Stoning bottles was a badge of youthful prowess, exceeded only by skill with that indigenous island invention, the bean-snapper. A slingshot by any other name, the bean-snapper relied for its muzzle velocity on approximately 15" of inner-tube rubber, cut about an inch wide. Over one end, we placed a slipknot of heavy twine and poked its loose ends through holes in a leather sling from which we could snap a smooth pebble the size and shape of a small bird’s egg much farther than the arm can throw.

On Tuesdays and Fridays without fail, a score of us would climb aboard Johnny Murray’s flatbed truck for a ride to the movies, westerns mostly, at Redmen’s Hall over on neighboring Orrs Island. Those truck rides were social occasions still well remembered. Even today, men and women in late middle age who I meet in the General Store re-introduce themselves as fellow riders on Johnny’s truck. As I strain to match their lined faces with the names and features of long ago, I think how they must see time written on my own. We remind each other of Johnny who was killed in action in World War II, and then, sad memories refreshed, we talk of the weather and other useless things. Once, walking home past the island church, I read Johnny’s name off a roadside plaque and wondered that a loss so long ago is still so affecting, a piece of immemoriam stuck fast while other fragments slip away.

The steamboat Aucocisco docked at noon each day, hooting a summons to all who felt they should mingle or for whom “picking up the mail” was their excuse for lingering until it was sorted at nearby Sinnett’s General Store. Gathering at noon on the steamboat wharf was a social moment that broke the day into its natural halves. At twilight, the steamer returned—its hulk looming large in the gathering dusk, heading straight toward us, thumping to a halt, and squealing against the pilings. We secretly hoped Captain Morrill would someday bring her in fast enough to carry all away, but this was only wishful. Morrill was a seagoing capo di tutti capi, who even when the bay blew rough could make his passengers forget that his aging vessel once graced more tranquil waters as a riverboat. Once tied at the wharf, he beamed down from his lofty wheelhouse, exchanging pleasantries with the wharf regulars and watching over the offloading of cargo. To us kids he was totally awesome.

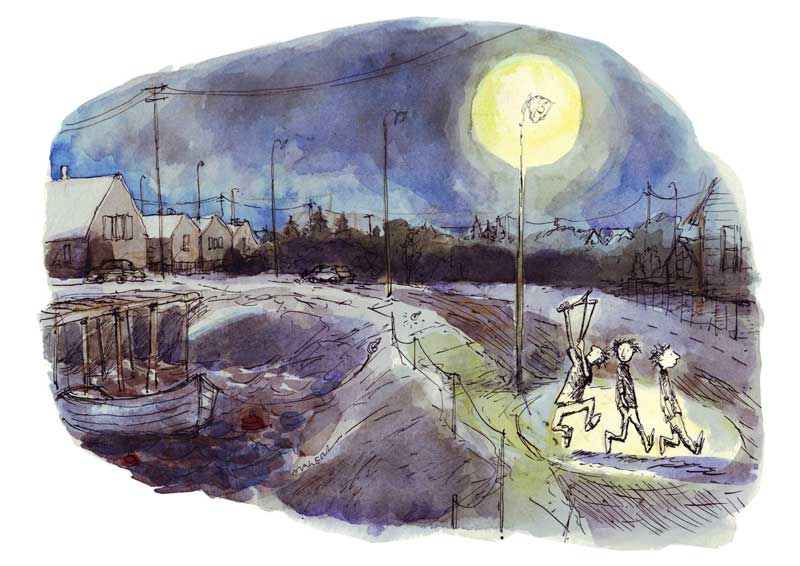

From the wharf we’d wander home as night threatened. Darkness gave us cover for occasional deviltry and fresh targets. Streetlights called attention to themselves, and stones by the roadside were always plentiful enough to take them out. Some boasted that they could bust ’em faster than the power company could replace them. I did not hesitate to join in, for the crime was without guilt; and it spoke to retribution, for how dare the night be lighted when the day had lost its glow? We made it dark until the dawn returned to give us back the cove and all the wonders of a now-lost youth.

Peter P. Hill taught U.S. diplomatic and Early U.S. history at the George Washington University for more than 30 years. He only missed summering in Maine during his four sabbaticals in France, and now resides in Brunswick.