It’s a hot September afternoon in Waldoboro. From down the road comes the sound of an old motorcycle. The bike shoots up the gravel drive followed by a rooster tail of dust, then glides into a small wooden shed. A moment later, Lincoln Davis walks out of the shed and with a big grin, extends his hand. Davis is a principle of Stetson and Pinkham, a respected Mercury outboard motor service center, and proprietor of one of the most incredible collections of vintage outboard motors—and the boats they ran on—anywhere.

Lincoln Davis has been collecting outboard engines and related memorabilia for years. It is all on display at a museum adjacent to his business, Stetson & Pinkham in Waldoboro. The engines all still run and displays include directions to get them going. Photo by Ted Hugger

Lincoln Davis has been collecting outboard engines and related memorabilia for years. It is all on display at a museum adjacent to his business, Stetson & Pinkham in Waldoboro. The engines all still run and displays include directions to get them going. Photo by Ted Hugger

Davis shows off his restored 1958 Corson. Photo by Polly SaltonstallIn addition to being one of New England’s top Mercury outboard mechanics, he’s also a wicked-good storyteller. It only takes Davis a few moments to go straight into tour guide/outboard motor historian mode. Walking into the repair shop, he waves his hand at an amazing collection of boats in one corner, some of them leaning against the wall, bow to the ceiling.

Davis shows off his restored 1958 Corson. Photo by Polly SaltonstallIn addition to being one of New England’s top Mercury outboard mechanics, he’s also a wicked-good storyteller. It only takes Davis a few moments to go straight into tour guide/outboard motor historian mode. Walking into the repair shop, he waves his hand at an amazing collection of boats in one corner, some of them leaning against the wall, bow to the ceiling.

“That’s a 1926 B-class step-hydroplane that I built from plans from MotorBoat magazine. And that one is a B-class hydroplane, a '57 or '58. What they call a short-sponson Sid Craft. And with the fins, there on the trailer, that’s my '58 Corson. And this is a 1954 D-class hydroplane…there’s a couple of engines I run on this boat. The D-class is maxed out when you get close to the low 60s. Sixty-four miles per hour is the fastest you’d ever want to drive that boat.”

Davis is a high-speed fountain of boat and motor facts, and history. He’s also an extremely talented mechanic. Davis taught antique outboard maintenance at the WoodenBoat School, and for six and a half years was the outboard instructor for Mercury Marine’s Northeast certification and recertification program. He travels all over the state to service finicky engines—old as well as new.

Davis explains that this 1962-1963 Merc 1000E was the first ever 100-hp outboard engine as well as the first one painted black. A huge success for Mercury, it brought the company into the public eye. Photo by Polly Saltonstall“But take that same engine—or that same cubic inch displacement—on a modern version of that boat, and it does 110 mph.” Davis paused for a moment, and then continued. “So boat advancement and engine enhancement go pretty much hand-in-hand.” That last statement succinctly puts Davis’s interest and passion about old outboards and old boats into sharp focus. The technology behind the development of modern marine power over the years captivates him.

Davis explains that this 1962-1963 Merc 1000E was the first ever 100-hp outboard engine as well as the first one painted black. A huge success for Mercury, it brought the company into the public eye. Photo by Polly Saltonstall“But take that same engine—or that same cubic inch displacement—on a modern version of that boat, and it does 110 mph.” Davis paused for a moment, and then continued. “So boat advancement and engine enhancement go pretty much hand-in-hand.” That last statement succinctly puts Davis’s interest and passion about old outboards and old boats into sharp focus. The technology behind the development of modern marine power over the years captivates him.

For the most part, old boats and outboards find their way to his shop. They just show up and refuse to leave until they’ve been brought back to life by the “Boat Doctor,” as he was dubbed in a 2005 issue of Professional BoatBuilder magazine. “But the only boat that I ever sought out was the Corson,” he said with a sort of fierce pride. The Corson is a 1958 classic, 16 feet in length, styled in fiberglass, and replete with sweeping red fins. Corson only made this model that one year, and did not make many of them.

“A friend of mine…” (All of Davis’s stories seem to start that way. He has a host of friends who scour barns and sheds and old boatyards for vintage boats and motors. He affectionately calls them bird-doggers.) “A friend of mine found the Corson after nearly five years of searching, and he found it right down in Yarmouth. I agreed with him that it was probably a Corson, but neither of us was really sure. So I sent the pictures of the old boat to Jerry Corson, the guy who built the boat in the first place.” A smile crept across his face. “It was in such rough shape. Jerry got back to me and said ‘I don’t know what the hell that thing is!’”

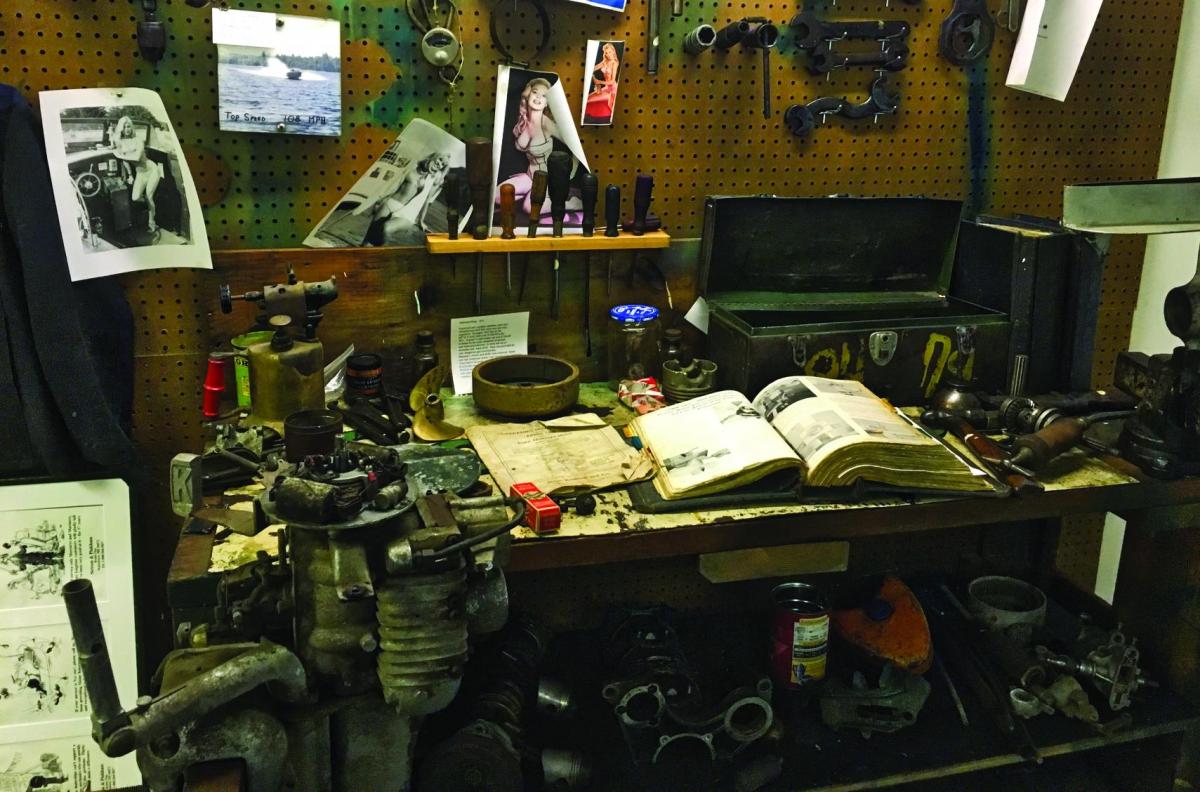

The workbench on display at Davis’s museum includes tools from his former shop, as well as other tools and decorations typical of a mechanic’s bench between the 1940s and 1970s. Tools were very expensive then, explains Davis. “A half-socket set was around $250 and a drill index was the same. You used a hammer and chisel a lot and Phillips screws were hated because nobody made a screw driver that worked flat bit screws.” Photo by Polly Saltonstall

The workbench on display at Davis’s museum includes tools from his former shop, as well as other tools and decorations typical of a mechanic’s bench between the 1940s and 1970s. Tools were very expensive then, explains Davis. “A half-socket set was around $250 and a drill index was the same. You used a hammer and chisel a lot and Phillips screws were hated because nobody made a screw driver that worked flat bit screws.” Photo by Polly Saltonstall

But that didn’t dissuade Davis, who bought it for $200. “The guy from Yarmouth came out, grabbed the 200 bucks, and ran back into his house slamming both doors shut. He just didn’t want me changing my mind; he couldn’t believe that I would pay that kind of money for that kind of boat.”

Davis convinced Corson that the boat was, in fact, one of his own, and more importantly, convinced him to restore it. Corson agreed, but Davis had to strip the boat before Corson would touch it. It took six gallons of paint remover to take off all of the layers of house paint that had been laid on over the years. “The hull was all cracked and beaten, the seats were broken, and it was just a mess with sheet rock screws holding it together. It was horrible. But it was what I was looking for.”

Corson breathed new life into the old classic and Davis mounted a vintage 1958 Mercury Mark 78 outboard on the back. “Truth is, I could have bought a brand new Corson for what I paid to have that one restored. But it’s been well worth it. I’ve probably used that boat more than any other boat I’ve owned. I taught my kids how to ski behind that boat and motor.”

One of the hallmarks of true passion is the uncanny ability to see the possibility in the most improbable. So imagine Davis back in 1974. He’d just bought Stetson and Pinkham was kicking around out back in the piles of old motors and scrap parts and pieces. Sticking out was the handle of an old outboard.

Davis and his son, Andrew, built this PB4, a Custom Craft kit boat, in the 1990s. The engine is a 1950 KG9 Mercury 25 HP with a Quicksilver leg and 1:1 lower unit for racers. Photo by Ted Hugger

Davis and his son, Andrew, built this PB4, a Custom Craft kit boat, in the 1990s. The engine is a 1950 KG9 Mercury 25 HP with a Quicksilver leg and 1:1 lower unit for racers. Photo by Ted Hugger

“This old 1927 Johnson K-35 lay buried right up to the handle,” he remembered. On a whim, he restored it. “With some advice from my father, I was able to rebuild it and get it running.” (Davis’s father raced outboards back in the 1920s.) The pistons were so rusted, it took six months of soaking and working to free them up. “What’s amazing is that the coil and condenser are original equipment, yet they still meet spec after all of these years,” said Davis. More importantly, the motor still fires up and runs like a champ.

Davis’s collection began with that 1927 Johnson. The entire collection is now on display in a large room adjacent to the Stetson and Pinkham offices. His museum includes an old mechanic’s tool bench with vintage tools; photos, posters, and advertising materials; and of course, Mercury, Johnson, Evinrude, Champion, Chris-Craft and other motors of every shape and size, dating back to 1907.

“I have no idea how many engines I have out in the museum. I mean, you’ll just have to count them.” And he’s serious, because he’s not going to do it. He is more interested in technology. “I couldn’t care less if I have the first one or the latest one. What I’m interested in are the big changes in the technology as the outboard industry evolved. What did they change and why? How did they figure out magnetos? How did they design and improve carburetors?”

To date, Davis has video documented about 60 percent of his collection. Each of the mini-documentaries can be accessed on the Pine Tree Boating Club’s web site at www.pinetreeboating.com.

His fixation with engines is not limited to old technology. “I’m as interested in today’s motors as I am in the old ones. You can see the progression over the years and how people figured stuff out… You can see a lot of dead ends that the engine builders took, too. Engines or components of engines that just didn’t work out.” For example, Mercury and Champion built some spring-drive motors—shifting required going from neutral to forward to reverse through a set of springs and gears. While the technology didn’t really work, the companies learned valuable lessons.

“As a result of that project, Mercury figured out how to build an angled outboard. Instead of a 90-degree, straight up-and-down drive shaft,” Davis said, “they learned how to gear the drives so that the drive shaft could go down at an angle, and still have the propeller drive parallel to the waterline. It was one of those important developments that made production possible.”

Davis, who grew up in Marblehead, Massachusetts, moved to Maine with his family in 1964. Although his father was a notable sailor, Davis was more interested in engines. He bought a Mercury Mark 20 from a friend and began spending time at Stetson and Pinkham buying parts. Irwin Pinkham, seeing his potential, not only gave him a job at Stetson and Pinkham, but also sent him to Mercury outboard mechanic school in Rhode Island. Uncle Sam had other plans, though. Davis was drafted into the U.S. Army and ended up serving in Vietnam where he was a stevedore officer, overseeing the loading and unloading of boats.

After returning to Maine and graduating from the University of Maine, Davis learned Stetson and Pinkham was for sale. He made the plunge and has never looked back. Today, at a youthful 70 years of age, Davis works part-time as he gradually turns the business over to new partner Shawn Kelley.

I asked if Kelley shares Davis’s passion for vintage outboards. “No, but he does have a strong interest in new outboards, and he’s a very good technician. Most importantly, he’s really good with the customers.”

Davis remains fascinated with engines and boats, “even the new stuff—direct injection, four-strokes, supercharged. Here’s what’s interesting, though. Since 2008, there’s been a complete reversal in the industry. Prior to 2008, everything was about electronic controls and joy-stick piloting. All very, very expensive electronically controlled systems. Now, all the new engines—the money-makers for Yamaha and Mercury—are mechanical shifts in the 150- to 200-hp range. And they’re making them simpler and cheaper, lighter weight, and they just plain run better.”

“The customers spoke,” Davis said. “They want good-running engines that don’t need special treatment and don’t have electrical problems.”

Davis led the way out back to a small shed and stopped in front of the long sleek bow of a classic runabout. “A friend of mine knew a lady who was having an auction that I went to last year,” said Davis, launching into another story. “There was a 1932 Old Town Sea sitting in a barn. I didn’t want it, and nobody was bidding on it. My friend said ‘Oh Lincoln, you’ve got to give her 150 bucks for it.’ And I said ‘Nope, I just don’t want it.’ Well, two weeks after the auction, my friend calls me up and says ‘she’s giving it to you.’ My reaction was ‘Oh my God, I don’t want that thing, I don’t need that thing.’ But I rebuilt it last winter, anyhow.” That’s the trouble. Once Davis gets engaged in something, he simply can’t walk away from it.

The 16-foot-long boat had been perched on a 12-foot trailer for more than 15 years and was splayed open and rotten. He set it out on blocks, repaired a hole in the bottom temporarily with sheet rock screws and glue. “Then I piled about 600 pounds of rocks in the bottom and with a garden hose, filled the hull full of water. Under the weight of the water and rocks, the hull slowly came back relatively even with the help of athwartship pipe clamps to hold the hull shape.”

Davis stripped off the fiberglass that had been applied to the wooden hull back in the 1950s, re-sheathed the hull with cloth and West System epoxy, replaced six feet of keel and 22 ribs, and installed new floor boards. Finally, he built an elegant round wooden steering wheel, since the original was missing. A vintage 1929 Johnson V45 completed the restoration.

“I like running it. The hull form is different and the way she handles is different—it’s a lot like a sports car,” he said, running his hand over the long, rounded foredeck.

On a trailer outside of the shed is a 1958 Glasspar Seafair. Once unwanted, the 17-foot Seafair also found its way to the unwilling doctor by way of yet another friend. Then it sat in his field for five years, until, like the Old Town, it spoke to Davis. After two years of work, the boat now sits ready to launch at a moment’s notice, with its cool, 1963 Mercury 1000 long-shaft outboard on the transom.

Surrounded by his collection of outboards and the smell of two-stroke oil, Davis is in his element, a keeper of the faith who’s waiting for the next call from a friend.

Ted Hugger owns and operates the Cod Cove Inn in Edgecomb, Maine, with his wife Jill.

For More Information

The Stetson and Pinkham Outboard Motor Museum is open year round, Monday through Friday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. and by appointment.

Stetson and Pinkham

1992 Winslow Mills Road

Waldoboro, ME 04572

207-832-5855; www.stetsonandpinkham.com