Photographs by Don Dunbar

After bringing a big ship into Eastport, Bob Peacock has to steer it out again. Clear of the rocks and fickle tides, the Thorco Copehagen is bound for Tunisia with a load of Maine wood pulp, and Peacock climbs back down the Jacob’s ladder to the waiting pilot boat.When the pilot boat pulls away, and leaves me dangling over the side of a 478-foot freighter on a wet ladder, at midnight, plowing along several miles from shore with nothing but black water and foam racing below, it’s like a bad dream.

After bringing a big ship into Eastport, Bob Peacock has to steer it out again. Clear of the rocks and fickle tides, the Thorco Copehagen is bound for Tunisia with a load of Maine wood pulp, and Peacock climbs back down the Jacob’s ladder to the waiting pilot boat.When the pilot boat pulls away, and leaves me dangling over the side of a 478-foot freighter on a wet ladder, at midnight, plowing along several miles from shore with nothing but black water and foam racing below, it’s like a bad dream.

“I wouldn’t have invited you if I didn’t think you could do it,” says Bob Peacock. Along with Captain Gerald Morrison, Peacock is one of two pilots licensed to bring large ships through the treacherous tides at the mouth of Cobscook Bay.

Since 1789, states have regulated pilots in their respective coastal waters. Both of Eastport’s pilots work under the auspices of the Maine Pilotage Commission, which requires the use of local pilots for foreign flag vessels and United States vessels engaged in international trade. The law applies to vessels with a draft greater than nine feet, the big ones that cross oceans and approach strange ports in the night or day, uncertain of the local conditions.

The idea of jumping off a relatively small boat onto a fast-moving ship, in the dark, when the water temperature is around 50 degrees, evokes a number of feelings that coalesce around one word: fear.

Ultimately, Captain Garcia is responsible for his ship, and Bob Peacock must ask permission before taking control of the Thorco Copehagen. Here, Peacock confers with Garcia in the role of advisor.

Ultimately, Captain Garcia is responsible for his ship, and Bob Peacock must ask permission before taking control of the Thorco Copehagen. Here, Peacock confers with Garcia in the role of advisor.

At age 66, Bob has made well over a thousand trips in and out of this bay, and hasn’t fallen between a 10,000-ton freighter and a pilot boat yet. But he knows pilots who have. “Debbie Dempsey,” says Bob. “A wave pulled her off the ladder on the Columbia River Bar, out in Oregon. They got her back quick.”

Another pilot, Kevin Murphy, fell under similar circumstances on the Columbia River Bar six years before Dempsey’s 2012 incident. He was not as lucky as Dempsey and died after being run over by the pilot boat.

On this cold October night, with a stiff breeze out of the north, there’s not much time to think about peril as we cast off from the Eastport fish pier. Capt. James Smith steers us out of the harbor and toward the designated pilot boarding area in Grand Manan Channel, a half-hour run. Ian O’Hara stands aft; as safety man it’s his job to avoid any mishaps, and react quickly should anyone end up in the water.

Before leaving the dock, Bob had strapped a lightweight flotation device on me and tested the strobe light. He’d shown me a little yellow tag on the life jacket. “If you go in, pull this.”

The incoming vessel is empty, Bob warns. The propellers may be close to the surface, drawing water in from the sides. “The important thing to remember if you go in is to swim away from the ship as fast as possible,” he says. I mention something I’d read about having about 10 minutes of effective movement in cold water. “In this water, I doubt if you’d have three to five,” he says.

As we approach the pilot boarding area, Bob radios the ship, the M/V Thorco Copenhagen, and asks them to hang their boarding ladder over the starboard side. Because of the wind, he asks them to turn west to block the waves for our approach. He also calls Fundy Traffic, the Canadian-based control center for vessel traffic in these waters.

As we close with the ship, details of the floodlit deck resolve, and a spotlight shines down on the Jacob’s ladder hanging off the side. Bob goes first, leaping from the pilot boat and scrambling up the side of the racing freighter. He makes it look easy. Then it’s my turn.

It’s all in the movement, leaving a boat in motion, grabbing onto a huge freighter in motion, the feel of cold rough hemp in hand, feet on wet wood rungs—Bob warns me to keep a grip on the rope. Overcoming the desire to hang on for dear life, I start climbing toward the light. It’s the only way. The ladder ends at deck level. I look for the next handhold, a wet and slippery stanchion, and I’m up. Bob stands there waiting for me. It’s over.

We climb the tower to the bridge. There in the warmth and darkness lit only by instrument lights, we meet the captain, Teofilo C. Garcia. He asks how we want our coffee.

Bob’s next challenge is to thread this 10,000-ton ship, which had just journeyed from Florida, through the narrow channels and powerful tides in Head Harbor Passage and Cobscook Bay.

“The wind and the tide are the real issues here,” he says. When the tides are running at four knots a small problem can become a major emergency in seconds. “We have our system. Slow and steady.” The complex process involves a number of challenges, language being the first.

“It is not as bad as it used to be,” Bob says. “Nowadays everyone speaks English.”

It just depends on how well.

“Can I have the con?” Bob asks the captain.

Captain Garcia looks at him, and you can almost hear the tumblers clicking as he works to translate what has been said.

“The ship. Can I have the con?” repeats Bob.

“Oh yes. Yes.”

Bob introduces himself to the helmsman, checks course and speed. He asks the captain which way the propellers turn, which can affect the steering of the ship in reverse. He asks about bow thrusters, propellers in the sides of the ship near the bow that are used for the final maneuvers into the dock. “What is the distance from the bridge to the bow?” he asks.

“One hundred thirty four meters,” says Captain Garcia.

Bob sets up his own navigation instruments: a small tablet with a GPS chart showing his position, and a small transmitter that records his position every ten seconds. “Every time I call Fundy Traffic, it sends them a burst of data: our position, course, speed, all that.”

As part of their lengthy training, harbor pilots must be able to draw a chart of these waters, including depths, from memory. In addition, pilots must hold an unlimited Master’s license, enabling them to captain any ship at sea, and apprentice for 50 trips under a licensed pilot who is certified for that area. Bob is certified by both the Federal Government and the State of Maine, and is qualified to pilot vessels in a number of other ports, including Valdez, Alaska.

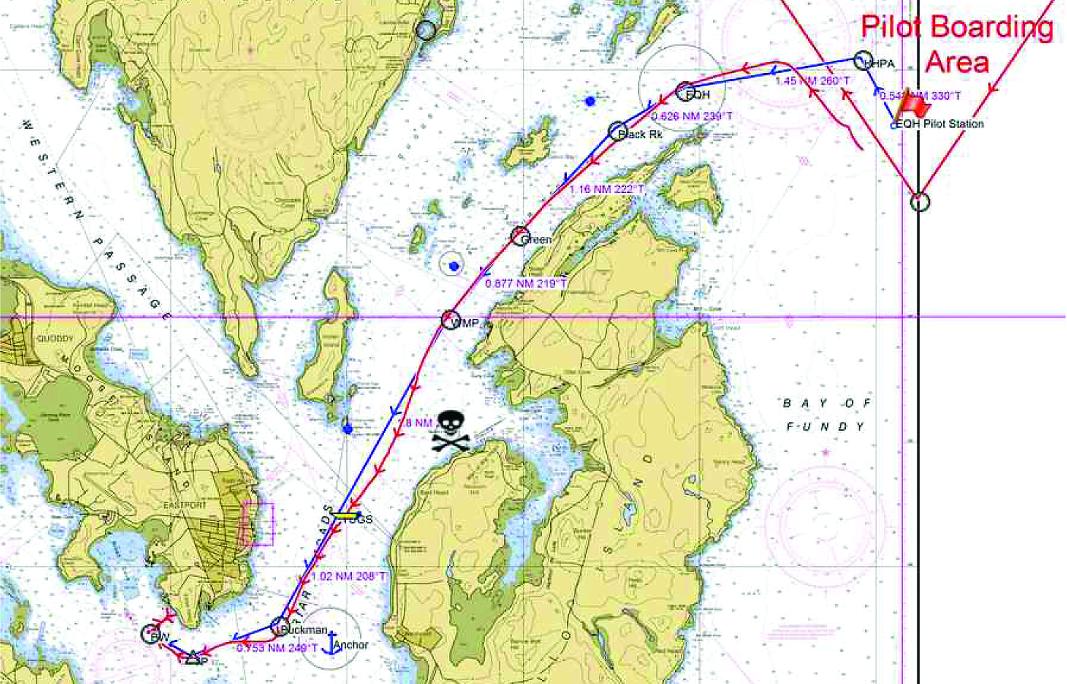

A computer program shows the charted course (black line) and the course made good in the strong tides around Eastport. “Slow and safe,” is how Bob Peacock brings the massive ships in through the needle of Head Harbor Passage and Cobscook Bay. Chart courtesy Bob PeacockAs the big ship enters the confines of Cobscook Bay, Bob checks in with Fundy Traffic again. “If there’s a ship coming down from Bayside, I can’t see it,” he says, referring to a Canadian port up the St. Croix River. The laws of physics say that the greater the mass in motion the harder it is to stop—or steer—and a freighter represents a considerable mass. “Head Harbor Passage is not where you want to meet another ship,” Bob adds. For an hour he has been running the ship at a slow ahead speed of five knots. The tide is running at another 3 knots, which means the ship is traveling at almost 9 knots. “We like to keep it under 10,” says Bob. “Whales.” The waters of the outer Bay of Fundy are a late summer and early fall feeding ground for the few hundred surviving North Atlantic right whales. Eighty percent of whale deaths for which a cause can be found involve ship strikes. At night there is little chance of avoiding a slow moving whale in the ship’s path, but once inside the bay the odds of encountering a whale decrease dramatically.

A computer program shows the charted course (black line) and the course made good in the strong tides around Eastport. “Slow and safe,” is how Bob Peacock brings the massive ships in through the needle of Head Harbor Passage and Cobscook Bay. Chart courtesy Bob PeacockAs the big ship enters the confines of Cobscook Bay, Bob checks in with Fundy Traffic again. “If there’s a ship coming down from Bayside, I can’t see it,” he says, referring to a Canadian port up the St. Croix River. The laws of physics say that the greater the mass in motion the harder it is to stop—or steer—and a freighter represents a considerable mass. “Head Harbor Passage is not where you want to meet another ship,” Bob adds. For an hour he has been running the ship at a slow ahead speed of five knots. The tide is running at another 3 knots, which means the ship is traveling at almost 9 knots. “We like to keep it under 10,” says Bob. “Whales.” The waters of the outer Bay of Fundy are a late summer and early fall feeding ground for the few hundred surviving North Atlantic right whales. Eighty percent of whale deaths for which a cause can be found involve ship strikes. At night there is little chance of avoiding a slow moving whale in the ship’s path, but once inside the bay the odds of encountering a whale decrease dramatically.

Periodically Bob calls out a course change to the helmsman.

“240,” he says.

“240,” says the helmsman.

“Dead slow,” says Bob, reducing the ship’s speed in anticipation of a tug hook up. The tug Jane McAllistair idles off Eastport, ready to tie onto the stern quarter of the ship prior to the final approach to the Federal Marine terminal on the west side of Eastport.

Looking down from the bridge, Bob talks tug captain Charlie Lepin into position. I ask why we are connecting to the tug while still a couple of miles from the dock. “Because it’s easy,” says the man of experience.

A few minutes later we enter a serious tide rip. “240,” Bob says to the helmsman. Moments later he makes another correction. “250.” Soon he has the helmsman steering 270 but with the tide pushing us the course made good is 200; the ship is pointed toward the dock but is actually moving away from it. “I’m going to have to give her some engine to get back on course,” says Bob. He advises the tug and then calls for more speed.

“See that line in the water up there,” he says, pointing to where the surface of the water goes from rough to smooth. “When we cross that everything changes.” He has to anticipate the slackening of the current and cut the ship’s speed before it reaches calmer water.

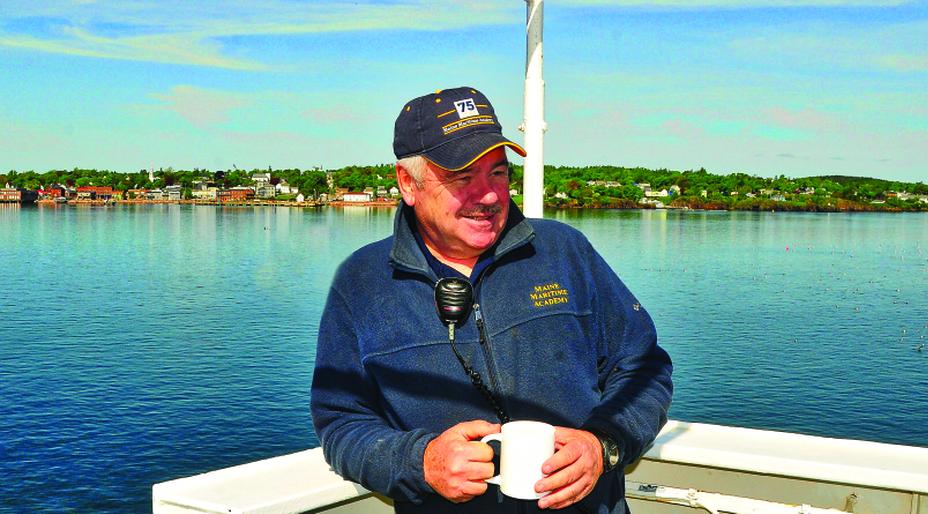

In addition to his work as a pilot, Captain Peacock stays busy. Operations manager for the seafood processing company Truefresh, he has been an Eastport City councilor and serves on the Maine Maritime Academy’s Board of Trustees, which he chaired for five years.

In addition to his work as a pilot, Captain Peacock stays busy. Operations manager for the seafood processing company Truefresh, he has been an Eastport City councilor and serves on the Maine Maritime Academy’s Board of Trustees, which he chaired for five years.

Gradually Bob gets the ship back on course and moving slowly toward the dock. It’s 2:15 in the morning. “We’re just killing time now,” he says. “Waiting so we don’t have to try and get her in there with a fair tide.” By 2:30 Bob has the ship lined up with the dock abeam. Balancing his use of the bow thrusters and the tug aft, he slowly slides the ship sideways toward its mooring. Bob brings the ship to a complete stop 100 meters from the dock. “Just to make sure we have control. Out here we still have options, in case we have to get out of Dodge. If we lose power in the ship or the tug we can drop anchor or do whatever we have to do.”

As the tide slackens Bob brings the ship to the dock, and directs the making fast of all the mooring lines. He points to his plan, which predicts a docking time of 2:47 a.m., and the clock on the bridge, which reads, 2:47 a.m. “I could bring her in without a tug,” he says, “pull in to the dock and come full astern. But that kind of stuff catches up with you, better to go slow and safe.”

The Eastport Port Authority built its new facility in 1998, with funding from a state bond issue. That was fortunate, because the breakwater the ships used to use to load wood pulp and cows—the primary exports from this port—collapsed in early 2015.

Captain Garcia will barely have time to sleep. He must prepare for a U.S. Coast Guard inspection at 8 a.m., before clearing U.S. Customs and Immigration. At noon the Thorco Copenhagen will begin loading wood pulp bound for Tunisia and Egypt. Garcia asks Bob about going into town, and learns there is no taxi service in Eastport, and the town does not have much to offer other than a few restaurants. “You can walk into town,” Bob tells him. “It’s about 20 minutes.”

But Captain Garcia and his crew will not have much time to enjoy the sights in one of the most remote little ports in the United States. “Eastport is the fastest wood pulp loading port in the world,” Bob says. He will be back aboard in 36 hours to guide the newly laden ship into open water before climbing down the Jacob’s ladder to ride the pilot boat back home.

Paul Molyneaux lives in East Machias and has written about commercial fishing in the New York Times and other publications. He is the author of A Child’s Walk in the Wilderness, published in 2013 by Stackpole Books.