Illustration by Ted Walsh

Illustration by Ted Walsh

I was nineteen and living on the Lower East Side of New York City in 1967 when I attended the Outward Bound School on Hurricane Island in Penobscot Bay.

I was recruited by a guy named Arthur Conquest. No lie. Big guy. Husky and fit. He explained the rigors involved and I had the good fortune to be convinced, and then I got a scholarship from the Boys Club of New York. The guys I had grown up with—the same guys I was still hanging out with—were starting to use heroin, so I was really lucky to be able to get out of the city for a month.

Their futures included addiction, prison, death by overdose, and AIDS.

Me? I became an attorney. But it wasn’t easy. The Boys Club and Outward Bound played an important part.

The Outward Bound concept dates back to the 1940s in England and the need to teach survival skills to sailors who served in the Navy.

My course lasted 26 days. You learned sailing skills, navigation, knots, and how to read and use a chart. You also learned rock climbing and how to rappel off cliffs. You ran, swam in the cold ocean, and were taught how to survive in the water.

Groups of students were organized into watches. I was in Grenfell Watch. Right at the beginning of the course, we were placed in big open boats—essentially whaling boats—with 10 big oars and two masts. The instructors set us adrift and told us to operate the boats. Best way to learn. No-one in charge.

Pandemonium. Oars colliding. Cursing. Then we were taught the proper commands, the names of boat parts, how to row, etc. The message was simple. Do things methodically. Cooperate. I can still remember some of the commands, “Stand by to give way together.” “Give way together.” (Those mean “Get ready to row the boat,” and “Row the boat.”)

Being in an open boat means if it rains you get wet. So foul-weather gear was really important. Slick yellow rain pants and a yellow hooded jacket.

Each course had a final expedition of maybe five days where the watch went out with other watches, with no adult instructor present. We sailed to different islands on a predetermined route, camping along the way. It was like a graduation exercise where you put into practice all the skills you had been taught. I was elected captain of the watch.

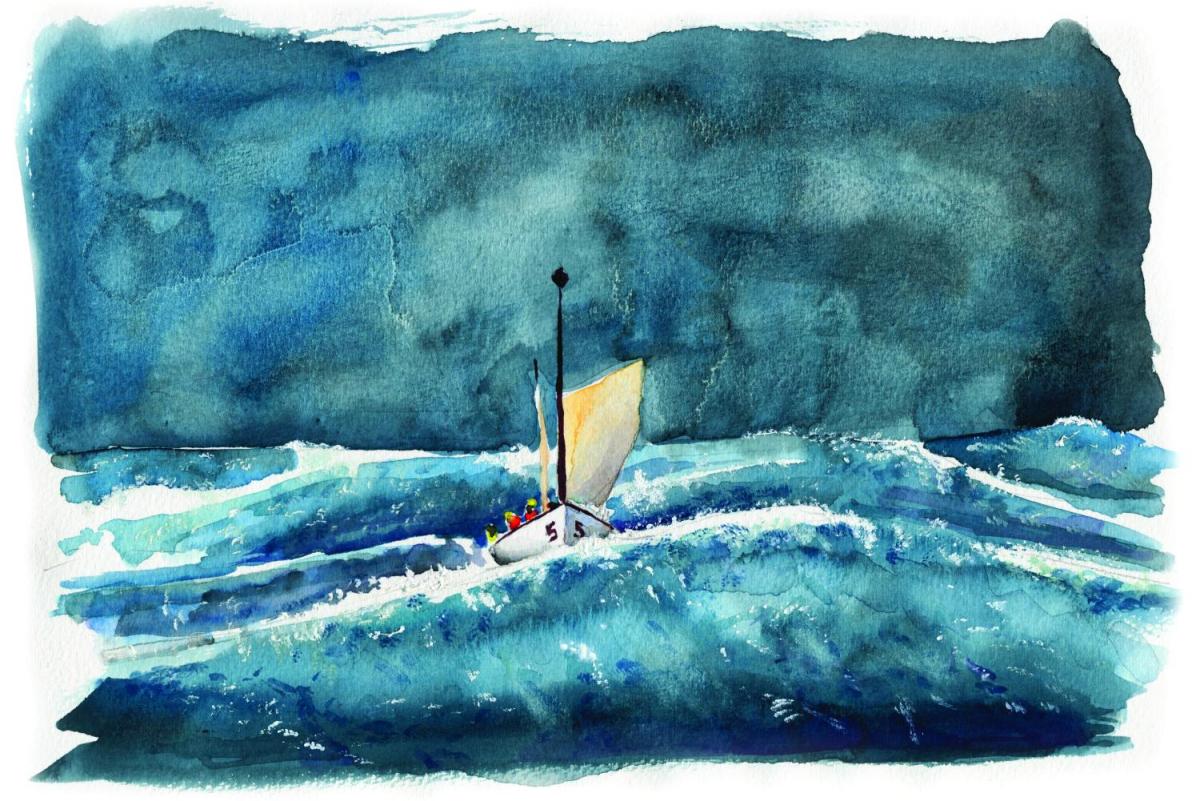

We had a storm on our expedition. I still have visions of it even though almost 50 years have passed: Wet howling wind. Grey sky. Dark, fast-moving clouds. Monstrous grey-green waves flecked with white foam blocking out the sky. A relentless wall of water. Boat smashing into a wave and freezing spray soaking my skin.

Luckily, the boat always had the same reaction: in one great jerky and ponderous motion, we’d launch up to the top of the next wave the same way one swings a bag of laundry up onto one’s shoulders.

At the top of each wave I’d stare in wonder at the churning ocean, orderly rows of waves spaced out like pews in a cathedral, only huge, and marching toward us. This was no serene church, though. I wished it were.

In the troughs between waves, I’d look left and right and see the power of the angry ocean. Waves looming up like furious giants intent on swamping our boat. My job as helmsman was to make sure the boat caught each wave squarely at the bow. Catch a wave sideways and the force could capsize the boat and wipe us out.

Rule No. 1: Use the rudder and steer the boat into the wave.

Rule No. 2: Be alert. Stay alert. No distractions.

Wet body, freezing hands, runny nose. Everyone’s sick. Everyone’s miserable. But there’s no way out. No 911 option. No pause button. Rocking, creaking and groaning boat, sails bulging, ropes twisting and straining. The next wave arrives and SMASH. It’s all repeated. Over and over. Hundreds and hundreds of times.

Each time the boat tilted and raced down the back end of a wave we had to lean back in order not to be thrown forward. These had to be at least 10-foot waves, because the boat fit into the back end of each wave before reaching the bottom. Man, 10-foot waves.

One day, years in the future, I’ll visit Notre Dame in Paris and I’ll see enormous cathedrals in Spain. But the awe these will inspire won’t be anything like the awe inspired by that storm.

You see, sitting in that boat in the midst of a turbulent ocean, I was vulnerable. That made all the difference. Quiet awe versus fearful awe. Although I wasn’t sitting safely in a quiet church, as each wave approached, I somehow did manage to utter a short prayer.

What I learned then, as a teenager on a pulling boat out on the ocean in a storm, was this: the ocean’s powerful and it doesn’t care, cooperate, or relent. Nothing personal. It’s just nature.

Rain and wind, forces of nature, can’t be turned on and off like a lightbulb. Don’t look around for help. There’s none. So hang on and ride out the storm. Survive.

After all, I survived 19 years on the Lower East Side. And that counts for something, right?

Jose A. Sosa is a retired attorney who now lives in Florida.