Stella Blue was designed to look like a classic Gentleman’s Racer, but with modern improvements. Photo courtesy Bob Stephens

Stella Blue was designed to look like a classic Gentleman’s Racer, but with modern improvements. Photo courtesy Bob Stephens

Beginning in 1905 and continuing today, wooden runabouts compete in an annual racing circuit of left-hand turns and thundering straightaways known as the Gold Cup. During the twenties and thirties, the competing boats became known as Gentleman’s Racers. Built with tropical wood, usually mahogany, and sporting skillfully planked hulls under multiple coats of varnish, these powerboats became icons, especially on lakes.

Given this storied tradition, it’s no wonder that naval architect Bob Stephens of Stephens Waring Yacht Design in Belfast, Maine, jumped at the chance to take on the job of designing just such a boat. His client was boatbuilder Reuben Smith, whose Tumblehome Boatshop in the Adirondacks specializes in the restoration and construction of classy runabouts and sailboats.

Built in 1922 and substantially improved in the 1930s when she began winning races, El Lagarto was the first-ever boat to win three Gold Cup races in a row. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithSmith had a customer who wanted a boat with elements of a Gentleman’s Racer, but that also would be practical for a family. The boat had to perform well as a cocktail cruiser on a small lake, as well as be a thrilling performer when the owner was out on his own and wanted to throw it around. Another essential feature was that the boat had to maintain her attitude as she came up on plane. The warped plane bottoms of the original boats forced the bows up in the sky as the craft came up on plane. This left their drivers blind through the middle speed range, which would not do on a small Adirondack lake populated by kayakers and others.

Built in 1922 and substantially improved in the 1930s when she began winning races, El Lagarto was the first-ever boat to win three Gold Cup races in a row. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithSmith had a customer who wanted a boat with elements of a Gentleman’s Racer, but that also would be practical for a family. The boat had to perform well as a cocktail cruiser on a small lake, as well as be a thrilling performer when the owner was out on his own and wanted to throw it around. Another essential feature was that the boat had to maintain her attitude as she came up on plane. The warped plane bottoms of the original boats forced the bows up in the sky as the craft came up on plane. This left their drivers blind through the middle speed range, which would not do on a small Adirondack lake populated by kayakers and others.

Smith knew a boat like this did not exist, and that this owner needed a completely new design.

“We knew we wanted a Gentleman’s Racer with a modern, essentially monohedron bottom,” explained Smith. He approached the Stephens Waring design office, knowing the firm’s reputation for innovation, style, and deep familiarity with modern wood construction. While the firm’s partners had not previously designed a high-speed powerboat, they had the necessary skill and historical savvy. Thus was the Stella Blue born.

Stephens Waring designed a hull that combines the improved planing of a deep-V with the sleek narrowness of a freshwater Gold Cup racer. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithMost of the early knowledge about planing boats was developed through Gold Cup and other American Power Boat Association-sanctioned racing. Given ample power, almost any light, hard-chined boat can plane, but despite ever-increasing speed records, prior to World War II most of them exhibited squirrelly habits such as pounding, stern-squatting, porpoising, erratic steering, and the occasional nosedive into a wave. Even the Navy’s vaunted Patrol Torpedo Boat was an uncomfortable platform from which to aim and fire a torpedo. All the aforementioned early hard-chined powerboats had twisted bottoms, beginning with a sharp V at the bow and transitioning throughout the bottom’s length to end fairly flat toward the transom.

Stephens Waring designed a hull that combines the improved planing of a deep-V with the sleek narrowness of a freshwater Gold Cup racer. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithMost of the early knowledge about planing boats was developed through Gold Cup and other American Power Boat Association-sanctioned racing. Given ample power, almost any light, hard-chined boat can plane, but despite ever-increasing speed records, prior to World War II most of them exhibited squirrelly habits such as pounding, stern-squatting, porpoising, erratic steering, and the occasional nosedive into a wave. Even the Navy’s vaunted Patrol Torpedo Boat was an uncomfortable platform from which to aim and fire a torpedo. All the aforementioned early hard-chined powerboats had twisted bottoms, beginning with a sharp V at the bow and transitioning throughout the bottom’s length to end fairly flat toward the transom.

I knew a little about all this, but Bob Stephens educated me further as I relaxed on the sofa of his conference room. After the war the Navy tasked Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate and former PT squadron leader Lindsay Lord to improve planing craft. He set to work making (and breaking) planing hull models, and afterward wrote the The Naval Architecture of Planing Hulls. It’s a book Stephens knows well. “Ray Hunt dogged Lindsay Lord in his later years at his home at Falmouth Foreside, in search of the secret of improved planing,” Stephens said. Thus did Ray Hunt enter the story.

The original El Lagarto has been preserved and is on display at the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake, N.Y. Note the stepped surface of her bottom. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithHunt emerged into naval architecture in the late 1930s at the beginning of a boom in marine recreation. Like many young yacht designers, he initially concentrated on sailboats. One of his first efforts was the International 110. This inexpensive sailboat was nearly flat bottomed, but, being narrow, heeled a lot, and in that attitude punched nicely through choppy waters. Some believe this registered in Ray Hunt’s genius consciousness, eventually to emerge in the form of a revolutionary ocean-going deep-V powerboat. The critical point was that the hull lines kept continuous longitudinal depth—there was no twist, nor was there upward rise toward the stern.

The original El Lagarto has been preserved and is on display at the Adirondack Museum in Blue Mountain Lake, N.Y. Note the stepped surface of her bottom. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithHunt emerged into naval architecture in the late 1930s at the beginning of a boom in marine recreation. Like many young yacht designers, he initially concentrated on sailboats. One of his first efforts was the International 110. This inexpensive sailboat was nearly flat bottomed, but, being narrow, heeled a lot, and in that attitude punched nicely through choppy waters. Some believe this registered in Ray Hunt’s genius consciousness, eventually to emerge in the form of a revolutionary ocean-going deep-V powerboat. The critical point was that the hull lines kept continuous longitudinal depth—there was no twist, nor was there upward rise toward the stern.

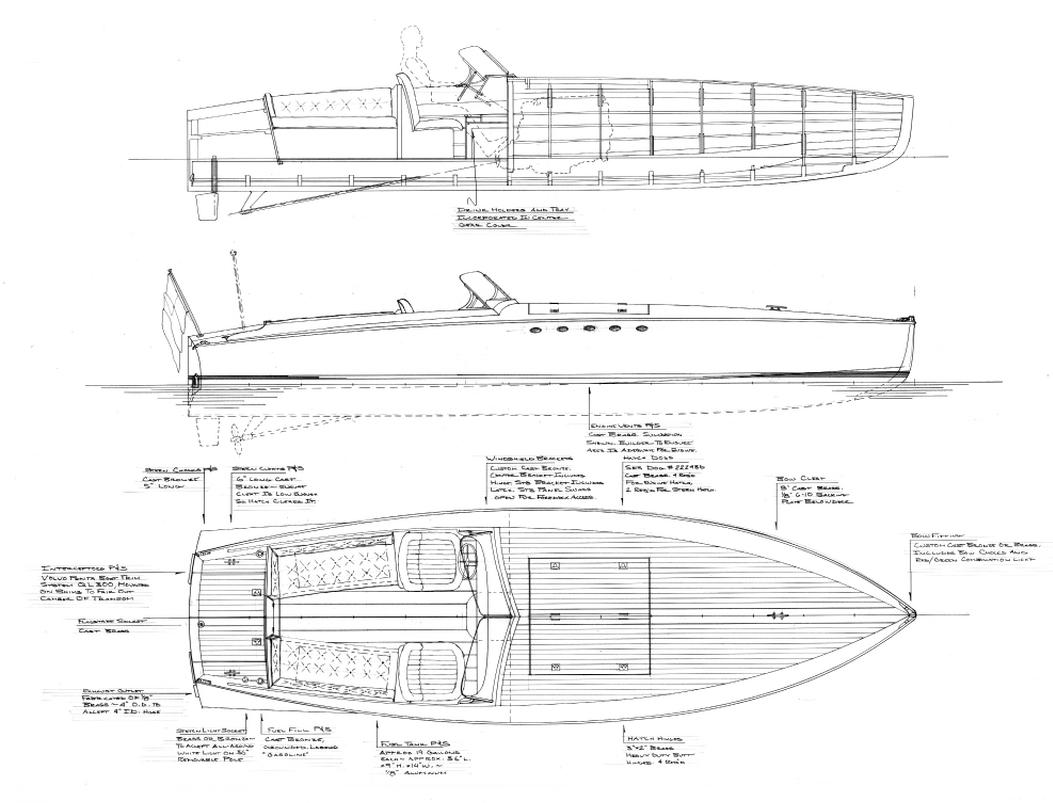

Courtesy Stephens Waring Yacht Design

Courtesy Stephens Waring Yacht Design

At the start of my conversation with Stephens, I was under the mistaken impression that Stella Blue was, like “Nessie,” a creature unique to lakes. Stephens gently explained that his design also will work well on salt water, thanks to his addition of Hunt-inspired elements to the design.

Smith’s client lives on a small lake just south of Lake George, where perhaps the most famous mahogany Gold Cupper of all, El Lagarto, won lasting fame. One of naval architect and powerboat designer John L. Hacker’s masterpieces, El Lagarto was one of those skinny, warped-bottom runabouts in vogue in the twenties and thirties. In her early years, the boat was not raced much. Then a second owner, George Reis, along with mechanic Dick Bowers, installed a powerful Packard engine and added five long shingle-like wedges to the bottom. Thus evolved the infamous “leaping lizard.” In 1933, she won the Gold decisively against strong favorites and, despite changes to the rules intended to diminish her dominance, proceeded to repeat her performance in the next two runnings and thereby create the first trifecta ever recorded for America’s signature powerboat race.

Unlike most racers from the 1920s, Stella Blue has a second seating area to accommodate more passengers. Photo courtesy Reuben Smith

Unlike most racers from the 1920s, Stella Blue has a second seating area to accommodate more passengers. Photo courtesy Reuben Smith

Stephens said the boat was called the leaping lizard not only because “lagarto” means “lizard” in Spanish but also because it bounced at high speed. He argues that the twisted bottom in these boats is hydrodynamically unsound. What he came up with instead is a hull that combines the narrowness of a freshwater Gold Cupper with the improved planing and docile handling characteristics of a Ray Hunt deep-V.

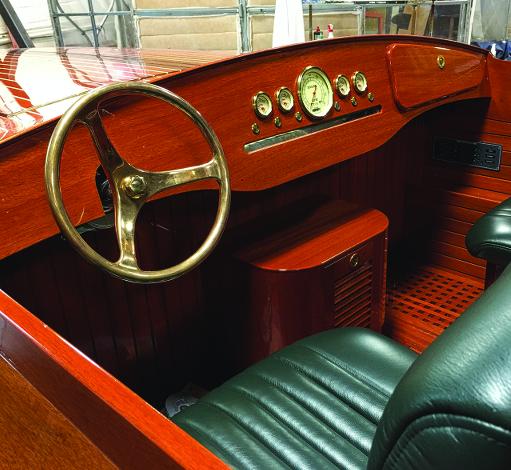

Stella Blue’s classy driver’s seat. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithThat new-fashioned bottom raised eyebrows when curious Lake Georgers visited the Tumblehome Boatshop during the two-year construction period. Then when the designers revealed a constant deadrise aft with a dihedral of 18 to 20 degrees, there was a collective sucking of teeth throughout the lakes district. Fortunately, Reuben Smith and his client had faith, and the boat’s performance proved to be excellent.

Stella Blue’s classy driver’s seat. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithThat new-fashioned bottom raised eyebrows when curious Lake Georgers visited the Tumblehome Boatshop during the two-year construction period. Then when the designers revealed a constant deadrise aft with a dihedral of 18 to 20 degrees, there was a collective sucking of teeth throughout the lakes district. Fortunately, Reuben Smith and his client had faith, and the boat’s performance proved to be excellent.

Stella Blue is powered by a marinized Chevy V-8 block that can yield a top-end speed of more than 50 miles an hour. The boat’s propeller has slightly less pitch than optimum for “the stretch.” This is because Stella Blue lives on a lake that is only two miles long, so acceleration and deceleration come into play. If she were to get feisty on much longer Lake George, Stephens indicated that with a more over-square prop and a featherweight driver, she might top 60 miles per hour.

There is more uniqueness in this design. Gold Cup replicas normally have only a tiny cockpit for two. Stella Blue has a second cockpit that can handle four more passengers, as well as a small swim platform with an integral swim ladder. This already-versatile runabout could also be outfitted to pull skiers or tubers.

An aft compartment with motorized hatches contains a swim ladder that folds out and then telescopes down. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithThe swim ladder was a serious design challenge, said Smith. It fits under the aft hatches, which are motorized. The ladder hinges and then telescopes down 4 feet. The ladder, swim platform, hydraulic steering, 33-gallon fuel tank, hatch actuators, and a two-stage muffler all fit under the stern deck.

An aft compartment with motorized hatches contains a swim ladder that folds out and then telescopes down. Photo courtesy Reuben SmithThe swim ladder was a serious design challenge, said Smith. It fits under the aft hatches, which are motorized. The ladder hinges and then telescopes down 4 feet. The ladder, swim platform, hydraulic steering, 33-gallon fuel tank, hatch actuators, and a two-stage muffler all fit under the stern deck.

The hull was vacuum bagged and cold molded. One thing that Stephens Waring brought to the design was the sense of how to engineer this sort of boat for this construction, said Smith. The designers lightened the frames considerably from a comparable, traditional runabout, but let the keel, logs, and clamps be massive, in order to have wide glue lands for the skin. They understood how to create the panels, and how to support them. Smith added that Stephens Waring’s plans were extremely accurate, and the hull required no fairing to speak of.

The runabout has been launched and running for one summer. Most observers would agree: Stella Blue is the happy result of expert wooden boat engineering, a keen compromise between aesthetics and versatile recreational use—in other words, a supremely satisfactory update to the vaunted Gold Cup class.

Contributing Author Art Paine is a boat designer, fine artist, freelance writer, and photographer who lives in Bernard, Maine.