A connection to the Wabanaki and their land

<

Cayard’s connection to his work is informed by a deeply held feeling that culture is as much a reflection of the land as it is of the people. His exploration of traditional Wabanaki culture has given him to better understanding of Maine’s native forest. The birchbark canoe is an outgrowth of that forest—its birches, whose bark is both thick and pliant; its cedar trees, whose wood is springy, light, and easy to split precisely; and its spruce trees, whose roots—the sinews of the forest—become the sinews of the canoe.

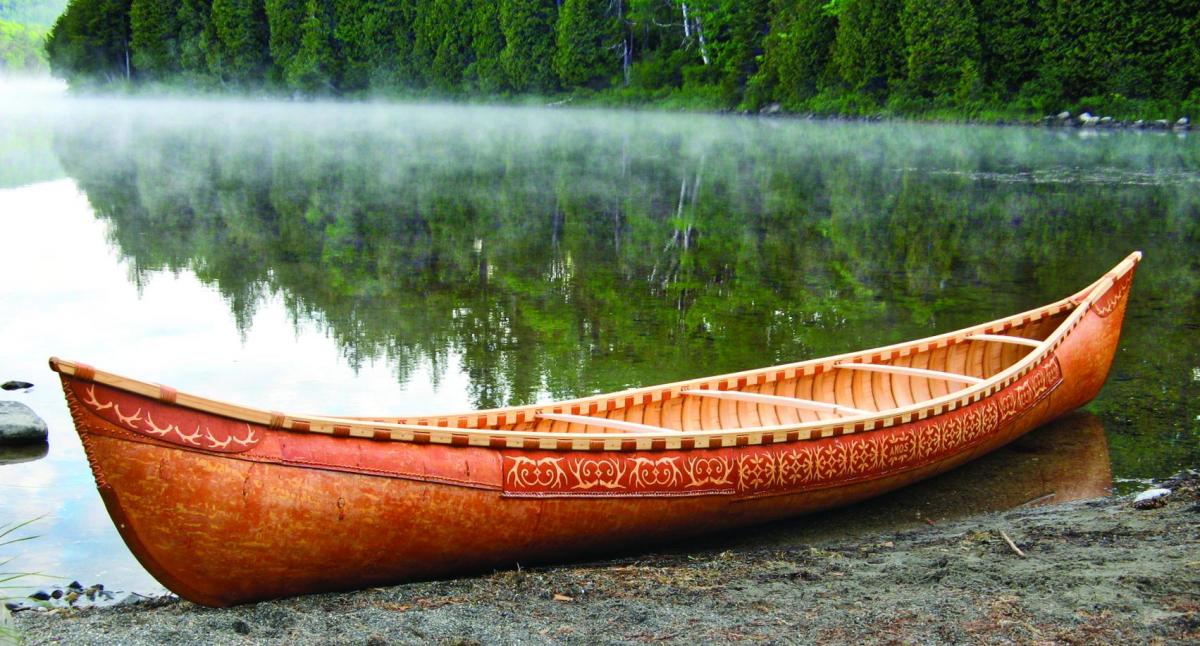

It hardly seems possible that these solid elements—bark, trunk, and roots—can be transformed into materials pliable enough to be used, essentially, as fabric, thread, and stays. But that’s what happens during the composition of this low, lean craft, which is characterized by a raking stem that swells to a rounded middle, then yields to a high tumblehome. Construction can take place in a couple of weeks, and involves an inside-out sequence of steps that starts with making and shaping the skin, then adding ribs and planking. (This contrasts with conventional boatbuilding—assembling a framework, then skinning it.) Essentially, the bark skin is laid out and sewn with spruce roots, and the gunwales attached, thus forming an empty envelope of bark. The envelope is then shaped and stretched by tucking the ribs under the gunwales and driving them tight against the bark, with the planking sandwiched in between. Copious amounts of hot water poured onto the bark keep it pliable during the process. When the ribbing is complete, gunwale caps are pegged and lashed to the top of the gunwales, and two headboards are installed in each end of the canoe. The seams are gummed with a mixture of pine rosin and lard, and the canoe is oiled inside and out with tung oil. On the outside, Cayard’s canoes also feature panels of decorative etchings.

Over the years, he has made more than 50 canoes, 30 on his own, and the rest as part of his workshops. Even after three decades, he’s still fascinated by the craft.

“I’m always learning, every time I build one,” he said. “It never gets boring: It’s such an aesthetically pleasing process. At the same time, it’s been a real treat to hang out with people whose traditions I’ve studied all these years. I feel like the culture belongs to the land. So this is something that makes me feel a connection with the land and the people here.”

Birch-bark Bible

Birch-bark Bible

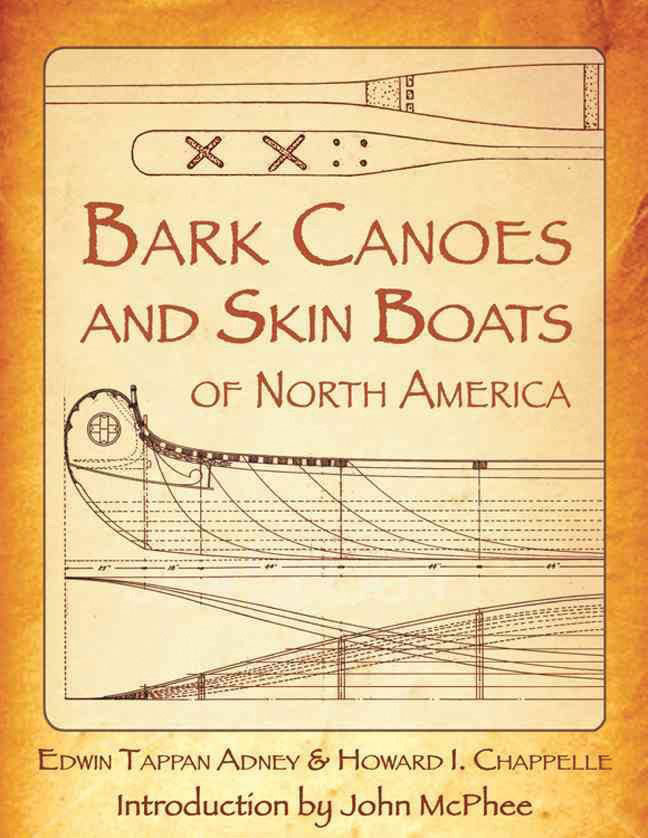

One of the greatest references for all birchbark canoe builders and fans is the epic tome, The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. Born in 1868, artist, writer, and photographer Edwin Tappan Adney first became interested in birchbark canoes when he spent 20 months with the Malecite tribe in Woodstock, New Brunswick in Canada. Researching native canoes and culture became a lifelong obsession. After his death, Smithsonian Institute curator Howard Chappelle compiled Adney’s papers into this book. First published in 1964, it includes black-and-white line drawings, photos and diagrams.

Laurie Schreiber has written for newspapers and magazines on the coast of Maine for more than 20 years.

Meet Steve Cayard and learn more about his craft at the Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors Show where he will be exhibiting some of his birchbark canoes, August 12-14, 2016 in Rockland, Maine.

Videos on birchbark canoes.

Watch a series of documentary videos produced by the Penobscot Nation and filmmaker D’Arcy Marsh that includes footage of the birch bark harvest, as well as the rest of the process of building a canoe: CLICK HERE

Watch a series of documentary videos produced by the Penobscot Nation and filmmaker D’Arcy Marsh that includes footage of the birch bark harvest, as well as the rest of the process of building a canoe: CLICK HERE