“Welcome to Brooklin—Boatbuilding Capital of the World.” Just up the driveway from that sign, on the side of State Route 175, the late Jim Steele made himself famous in the world of traditional boats by building wooden rowboats to an outstandingly seaworthy and pretty peapod design. Like the vegetable, a peapod is pointed at both ends. His 13-foot boats are so captivating in shape that Jim reportedly was flagged down on the Connecticut Thruway with one on top of his truck, and the boat sold right there by the side of the highway.

Ben Emory and his wife, Dianna, often row together in their peapod. Photo by Peter Ralston.

Ben Emory and his wife, Dianna, often row together in their peapod. Photo by Peter Ralston.

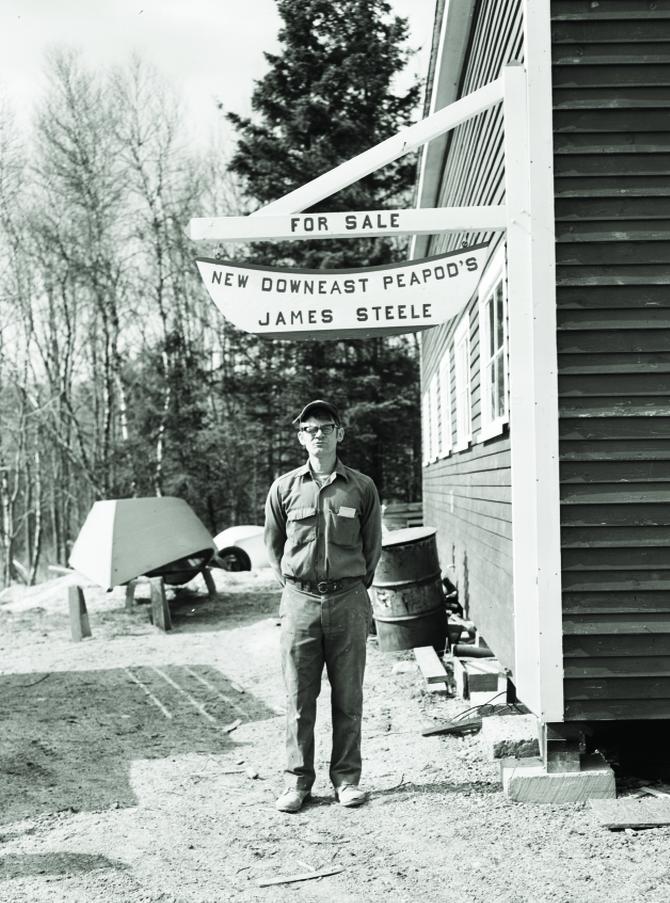

James “Jimmy” Steele was well-known for the sturdy, yet elegant wooden peapods he built in his shop in Brooklin, Maine. He died in 2008. Many of his tools and molds are now in the collection of the Penobscot Marine Museum. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

James “Jimmy” Steele was well-known for the sturdy, yet elegant wooden peapods he built in his shop in Brooklin, Maine. He died in 2008. Many of his tools and molds are now in the collection of the Penobscot Marine Museum. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

When my wife Dianna and I sought a new tender for our cruising sailboat, we kept our eyes open for one of the Steele-built peapods and found a used one right in our harbor. Jim used to say that he offered three versions: the Chevy with all paint; the Cadillac with a varnished sheer strake (the top plank), rails, and seats; and the Rolls Royce, on which even more is varnished. Ours is a Cadillac. I consider the painting and varnishing to be an enjoyable rite of spring, and admiring the results all summer long to be the reward. Dark green topsides with a varnished mahogany sheer strake make for fun elegance.

More fun than the elegance, though, is the actual rowing. Rowing has been important to me since I learned as a boy. In school and college I rowed competitively in four- and eight-oared shells. I even rowed in one more race after college, a highly unusual one. It was against the Somali Navy in the harbor of Chismaio, Somalia. We raced four-oared, undersized Russian lifeboats that came off a Somalian gunboat! Our destroyer’s goodwill visit was long before Somalia descended into its hell of utter chaos. These days I row for pleasure and exercise, and Dianna often joins me to row together as a pair.

Steele’s peapods tow especially well. Photo courtesy Ben EmoryIn our peapod we have explored many parts of the coast, and landed on many an island. We have accessed some of the finest conserved lands on the coast—the Isle au Haut District of Acadia National Park, Maine Coast Heritage Trust’s Marshall Island, the Perry Creek trails of the Vinalhaven Land Trust, Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge in Steuben, the tribal lands of the Passamaquoddy at the wonderfully named Moose Snare Cove, and the less wonderfully named Mud Hole shoreline of The Nature Conservancy at Great Wass Island, to mention just a few.

Steele’s peapods tow especially well. Photo courtesy Ben EmoryIn our peapod we have explored many parts of the coast, and landed on many an island. We have accessed some of the finest conserved lands on the coast—the Isle au Haut District of Acadia National Park, Maine Coast Heritage Trust’s Marshall Island, the Perry Creek trails of the Vinalhaven Land Trust, Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge in Steuben, the tribal lands of the Passamaquoddy at the wonderfully named Moose Snare Cove, and the less wonderfully named Mud Hole shoreline of The Nature Conservancy at Great Wass Island, to mention just a few.

The Mud Hole gave us one of our greatest peapod challenges. Dianna and I left the boat and set off hiking in early to mid-afternoon. We returned considerably later than planned, about an hour before dark. We are familiar with the 12-15 foot tidal range along that downeast Maine coastline, but we certainly were not paying adequate attention that day. We had left the peapod tied to a tree and floating over a sloping, seaweed-covered ledge, which was close to six feet out of water by the time we returned. The ledge ended in a vertical drop over which hung the boat’s entire back half. We could not risk serious damage by simply pushing the peapod over this cliff and hoping for the best. It would be hours before the tide would float her free again, long after dark, and mosquitoes were already descending.

Photographer Everett “Red” Boutilier took this photo of builder Jim Steele with the backbone of one of his peapods in 1975. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine MuseumAfter some pondering we foraged enough fallen small trees and branches from the woods to lay over the rocks to cushion the peapod’s bottom. We then hauled it farther up until we reached a point where we could lay down more trees and slide the boat at an angle back toward the water and around the cliff. We stripped off our sweaters and used them to pad especially problematic rocks. After a great deal of pulling and hauling of the heavy boat, with our sweaters stained with bottom paint and with our backs still intact, we finally relaunched just as darkness descended.

Photographer Everett “Red” Boutilier took this photo of builder Jim Steele with the backbone of one of his peapods in 1975. Photo courtesy Penobscot Marine MuseumAfter some pondering we foraged enough fallen small trees and branches from the woods to lay over the rocks to cushion the peapod’s bottom. We then hauled it farther up until we reached a point where we could lay down more trees and slide the boat at an angle back toward the water and around the cliff. We stripped off our sweaters and used them to pad especially problematic rocks. After a great deal of pulling and hauling of the heavy boat, with our sweaters stained with bottom paint and with our backs still intact, we finally relaunched just as darkness descended.

Exploring by oar has been a particularly educational way for us to see parts of the Maine coast. The Englishman River lies just east of the famous cruising destination of Roque Island, emptying into Englishman Bay below the long, south-facing beach at Roque Bluffs State Park. On a beautifully clear, early September day we anchored in the lee of that beach. In the peapod, with the current giving us a fast ride, we rowed under the road bridge into the estuary of the Englishman River. We were eager to see this landscape of low marsh with higher forestland behind. It was migration season and the sheer number of plovers and sandpipers along the winding channel was enthralling, as were the herons, ducks, and other birds that one would expect in such an area. That gorgeous afternoon of peapod exploration into the Englishman River was proof of the vital role that Maine estuaries play in the lives of migrating birds.

This peapod, so integral to our exploration of the coast, nearly met its end before we found it. Apparently, she had been caught between a boat and a dock earlier in her life and been significantly damaged. She was repaired, but after we bought her, we found that she leaked a bit when towed, although not when sitting on a mooring. At one point Jim Steele added some stiffening partial frames, which helped, but as years of use passed, I wondered how long she would last. In addition to some broken frames, the edges of some planks were moving out from the abutting planks. Jim, who was a bit of a character, said to me on more than one occasion, “This boat is good for nothing but burning, Ben.” I would always reply, “Jim, why would we want to burn her? We have so much fun with her.” I did sometimes say to Dianna, though, that our peapod was one possession that might not outlast us.

These worries eventually proved well founded. I was towing the boat up Frenchman Bay, beating into a strong northeast wind and serious chop, when she filled to the gunwales with water. The stress of the day had opened a seam. Heaving to, I brought the peapod near our sailboat’s transom and successfully fished out oars and other gear before I lost them. I did not know whether I could tow such a heavy drag the few miles to home, but I could not abandon a nearly submerged hazard to navigation. She was easier to tow than I anticipated, though. Soon enough I had her above the high tide line on our beach to await her fate—a rebuild or, finally, the burning.

By this time Jim Steele was no longer with us, having died in 2008, but Brooklin boatbuilder Eric Dow agreed to tackle reframing and refastening. One of the beauties of wooden boats is that they can be rebuilt if not too far gone. Thanks to Eric, this treasured possession should now outlast us.

Ben Emory is a life-long sailor who splits his time between Salisbury Cove and Brooklin. When not on the water, he has spent decades actively involved in Maine land conservation.