Photographs by Robert F. Bukaty

Wisps of sea-smoke rose from the Royal River in Yarmouth, Maine, as Capt. Ted Augustine and his three-man crew arrived at the Yankee Marina and Boatyard. Overnight the temperature dropped to 8 degrees-below-zero, creating a 2-inch layer of ice between shore and their dredging operation anchored about 100 yards away.

The crane hoists a shovel, full of mud and water from the Royal River in Yarmouth. Augustine, of Woodstock, Vermont, looked out toward the scow and downplayed the challenges of working on the water during a harsh Maine winter.

The crane hoists a shovel, full of mud and water from the Royal River in Yarmouth. Augustine, of Woodstock, Vermont, looked out toward the scow and downplayed the challenges of working on the water during a harsh Maine winter.

“Well, we have a crane operator who sits in the crane. So he’s all nice and warm. We have the first mate who sits up in that little booth on the Strider boat, so he’s nice and warm. We have the second mate sitting inside the container underneath the booth staying nice and warm and coming out whenever we make a move ahead. And I sit up in the ‘God box,’” he said.

Crew in the “God box”—aka the control booth—use satellite technology to guide the dredging operation. The “God box” is what Augustine calls the control booth where he uses sophisticated satellite positioning technology to guide the digging of muck that had been clogging the river’s navigation channel and anchorage basin.

Crew in the “God box”—aka the control booth—use satellite technology to guide the dredging operation. The “God box” is what Augustine calls the control booth where he uses sophisticated satellite positioning technology to guide the digging of muck that had been clogging the river’s navigation channel and anchorage basin.

“I run the controls for the big spuds that go up and down, and the lines that hold onto the dump scow,” he said.

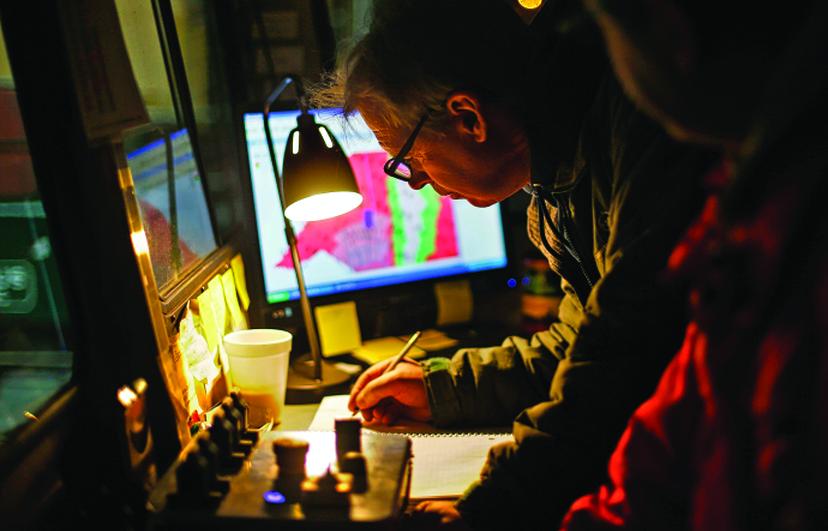

Capt. Ted Augustine makes notes at the 5 a.m. start of this work day. Digging times coincide with high tide.The crew works around high tide—which happened to be very early on this frigid January morning.

Capt. Ted Augustine makes notes at the 5 a.m. start of this work day. Digging times coincide with high tide.The crew works around high tide—which happened to be very early on this frigid January morning.

Shortly after 5 a.m. Augustine powered up the twin outboard motors on a metal-hulled push boat he uses to ferry the crew out to the barge. He put it in gear and let the propeller wash break up the ice around the dock, then crunched through the ice to the snow-covered barge. The push boat also is used to break up the ice in the dredging channel. That is until it became too thick for the 30-foot metal boat. Then Augustine hired Towline, a former 65-foot Coast Guard icebreaker, to break up the ice.

First Mate William Jedrey pilots one of the operation’s two push boats through the river’s ice-clogged waters.Second Mate Gregory Goodwin’s job requires him to periodically take depth measurements by leaning over the deck while holding a lead line. Working in snowstorms and sub-zero weather has taught Goodwin, of Harwich, Massachusetts, how to dress for the cold.

First Mate William Jedrey pilots one of the operation’s two push boats through the river’s ice-clogged waters.Second Mate Gregory Goodwin’s job requires him to periodically take depth measurements by leaning over the deck while holding a lead line. Working in snowstorms and sub-zero weather has taught Goodwin, of Harwich, Massachusetts, how to dress for the cold.

“I like Grunden and Gage, all that new technology that breathes. Before that it was cotton and wool. It doesn’t work,” he said.

Last year’s harsh winter weather with its record cold and snowfall made for sometimes challenging conditions on the job. The crew did not work during especially bad weather.

“We don’t want to put lives at risk,” said Augustine.

The dredging project began in October 2015 and by the time it was completed, 103,000 cubic yards of material had been removed from the Royal River navigation channel, returning the narrow, twisting waterway to a state unseen in more than a dozen years.

The first light of dawn colors the sky as the crew heads out to begin dredging.

The first light of dawn colors the sky as the crew heads out to begin dredging.  The ice on the river got so thick the crew had to bring in an ice-breaker.

The ice on the river got so thick the crew had to bring in an ice-breaker. Second Mate Gregory Goodwin uses a lead line to measure the depth of the section being dredged.

Second Mate Gregory Goodwin uses a lead line to measure the depth of the section being dredged. Captain Augustine climbs to the control booth of the Strider, a push boat used to move the dredging barge into position. In the background, the former Coast Guard ice-breaker Towline clears a path of open water.

Captain Augustine climbs to the control booth of the Strider, a push boat used to move the dredging barge into position. In the background, the former Coast Guard ice-breaker Towline clears a path of open water.

Robert F. Bukaty is a Pulitzer Prize winning staff photographer for the Associated Press based in Portland, Maine.