John O’Donovan, left, grew up building stage sets and Patrick Dole, right, spent his formative years working in his father’s bicycle repair shop. They bring a can-do attitude and a commitment to high-quality work at their boatbuilding shop in Searsport. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz. These days traditional plank-on-frame wooden boats might seem to be heading into the sunset. Few new ones are being built, few used ones are listed for sale, and those that are can often be had at such bargain prices that one could easily draw the dark conclusion that something must be awry with the entire species.

John O’Donovan, left, grew up building stage sets and Patrick Dole, right, spent his formative years working in his father’s bicycle repair shop. They bring a can-do attitude and a commitment to high-quality work at their boatbuilding shop in Searsport. Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz. These days traditional plank-on-frame wooden boats might seem to be heading into the sunset. Few new ones are being built, few used ones are listed for sale, and those that are can often be had at such bargain prices that one could easily draw the dark conclusion that something must be awry with the entire species.

This is far from the truth. Instead of representing some dismal end of the line, I would argue that the wooden boats that survive to this day are the pick of the litter. That’s because to stay alive over many decades, a wooden boat must be lovable enough to justify the time, effort, and expense necessary to keep it right. In other words, the dogs of the wooden boat fleet have bitten the dust; and, for the most part, only the good ones remain.

Take my 31' 51-year-old Concordia ketch, Vital Spark, as an example. Her cedar hull leaks less than a quart a day, her sails are pretty spiffy and keep her going at a reasonable speed, her diesel is reliable, and her simple systems are in good working order. Although she is not for sale, if she were, I might be able to get something in the neighborhood of $35,000 in today’s market. Yet—and I have this on good authority—to build a new boat anywhere close to her in terms of design and workmanship would cost something north of $600,000. That’s a remarkable differential.

So here’s the good news. Not only are there wonderful wooden boats around at good prices, in Maine at least, a potent cohort of shipwrights that possess the skills, the energy, and (how else can I put this?) the purest sort of love for wooden boats, stands ready to keep them sailing for decades to come.

Patrick Dole planks a peapod under construction in the Searsport workshop that he and John O’Donovan opened in 2008. Photo by John O’DonovanThe skillfulness and energy and down-to-earth smarts of Maine shipwrights (and others at notable yards outside of Maine, as well) means that, much like people these days, wooden boats are living longer and enjoying more active lives than seemed possible even a few years ago. It isn’t just old codgers doing the work, either. Young guys are setting up boatbuilding and restoration shops, a particularly hopeful sign for the future of these classics.

Patrick Dole planks a peapod under construction in the Searsport workshop that he and John O’Donovan opened in 2008. Photo by John O’DonovanThe skillfulness and energy and down-to-earth smarts of Maine shipwrights (and others at notable yards outside of Maine, as well) means that, much like people these days, wooden boats are living longer and enjoying more active lives than seemed possible even a few years ago. It isn’t just old codgers doing the work, either. Young guys are setting up boatbuilding and restoration shops, a particularly hopeful sign for the future of these classics.

Coastal Maine is a small face-to-face place where it’s natural to feel like a stakeholder. As a citizen of the coast, one of my pleasures is to reckon why the region holds such deep appeal, and why skillful young shipwrights are settling here instead of someplace else.

First of all there is the long tradition of boatbuilding in Maine. Even the smallest creek or cove (known as “eel ruts” in local parlance) saw at some point in its history a large vessel launched from its banks and sailed to kingdom come and back. Such boatbuilding traditions spawned generations of mentors, and mentoring thrives to this day to inspire, to keep standards high, and in an overall sense wrap a mentally challenging, physically taxing, and not particularly remunerative profession in a cloak of authentic nobility.

Another factor is that, compared to any other state, a lot of working waterfront still exists in Maine. This, in combination with hydraulic boat transport means that low-cost inland start-up shops can compete with long established boatyards. Finally let’s not forget Liberty Tool, an amazing used tool emporium where a young boatbuilder can equip him or herself with a complete set of traditional woodworking tools and the antique chest to store them in for under $500.

When John O’Donovan and Patrick Dole, doing business in a brick industrial building in Searsport as O’Donovan and Dole Traditional Boatbuilders, decided to settle in Maine, these were a few of the reasons that drew them. Smart, limber, strong, and committed to high-quality work at fair prices; these were the guys I sought out to refasten Vital Spark when her time came due a few years ago.

Although they came to the job highly recommended by a shipwright friend, as they planned out the refastening campaign and set to work, they exceeded my expectations at every turn. Removing original bronze screws can be ticklish work. Some you can just wind out, but others sheer off, or just spin, or you lose the slot and suddenly a screw that should take 30 seconds takes 30 minutes. To meet such challenges, John and Patrick armed themselves with an array of improvised tools (some of which they machined themselves). I never saw them flummoxed for more than a minute or two. Ultimately this meant the job progressed in record time, the biggest cost saving of all.

As the work moved along, my neighbor, Maynard Bray, a regular kibitzer at goings on like this, couldn’t help but notice how skillful they were. So he hired them to reframe a little Murray Peterson sloop that he had been storing in one of his sheds.

Since these jobs, as well as a long-term project on the Concordia yawl, Fabrille, O’Donovan and Dole have recently completed a massive job refurbishing the 63' Spaulding Dunbar-designed motor sailer, Ocean Pearl. At the point they took her on, Ocean Pearl’s teak hull, decks, and houses were in discouraged but not terminal condition. Her systems, on the other hand, could only be described as a tangle of obsolete dysfunction.

That John and Patrick dared, much less got hired, to take on such an immense project (Ocean Pearl weighs 70,000 lbs.) speaks to their life experiences and to their ability to learn by doing. Neither are the progeny of seafaring families. They came to a love of boats and the ocean all on their own.

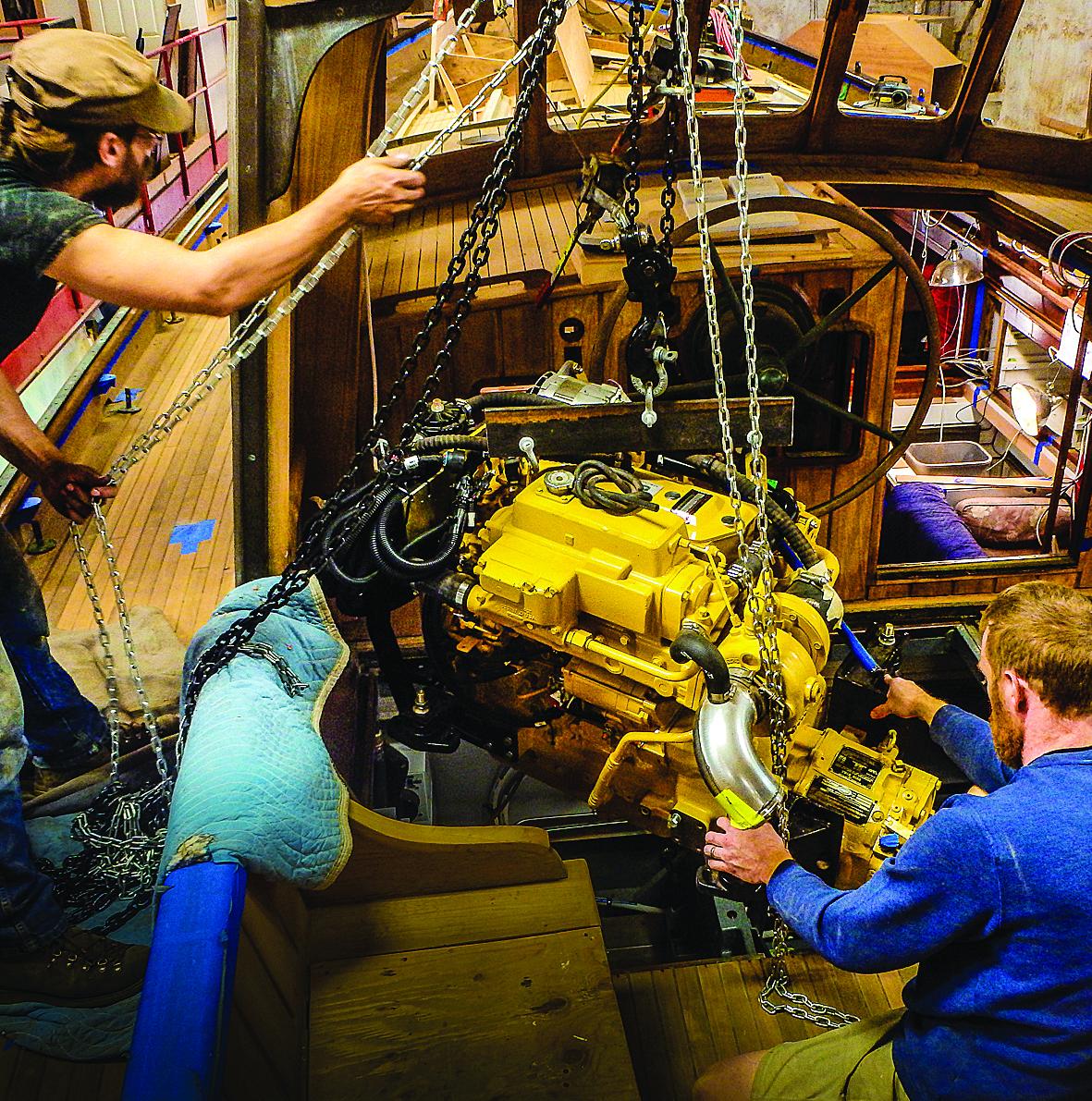

Even lovely wooden sailboats need power. Here the team at O’Donovan and Dole lowers an engine into Ocean Pearl as part of their extensive rebuild of the 63-foot yacht. Photo by Andrea Boothby

Even lovely wooden sailboats need power. Here the team at O’Donovan and Dole lowers an engine into Ocean Pearl as part of their extensive rebuild of the 63-foot yacht. Photo by Andrea Boothby

In the second half of his senior year in high school, somewhat by chance, he enrolled in a seagoing program aboard traditional schooners and showed such potential that he was offered a full-time job as a deckhand. The undertaking involved long periods of shipyard work in which he helped replank and reframe the schooner Harvey Gamage and re-power the schooner Spirit of Massachusetts. The experience was a life changer. Instead of heading off to college, Patrick decided to enroll at The Landing School in Arundel to study marine systems and traditional boatbuilding. What he learned there prepared him for a job at Rockport Marine, where he was able to do both systems work and carpentry. This experience turned him into one of the most respected “systems” men along the Maine coast.

Like many master practitioners, when confronted with a knotty problem Patrick finds a way to make complicated stuff simple: “Look at it this way, systems are mostly things that move stuff (like electrons or hydraulic fluid or fuel or refrigerant) through stuff to do stuff,” he said. “Simplifying everything in my brain is the way I go about it. And then (if this isn’t working) I call the guy who knows more than I do.”

John O’Donovan’s route into the world of wooden boats came via the world of Broadway theater. He was born into a family that had been building stage sets for three generations before John picked up a hammer (or in his case, given the rigorous apprenticeship traditions in the theater—a broom). He probably would have stayed in this line of work if, on a scene design assignment during a touring production stop in Seattle, one of his fellow stage hands hadn’t taken him for a sail on Puget Sound. This was his life-changer. From this point onward he began sailing all he could, bought an old fiberglass boat with a friend, fixed it up and sailed south before finally enrolling in the nine-month program at the Northwest School of Boatbuilding in Port Townsend, Washington.

From there, he landed a job at Ballentine’s Boat Shop in Cataumet, Massachusetts, one of the nation’s most highly regarded yards, restoring a 46' Herreshoff power cruiser built in 1931. He then took a job building a 28' Hanley-designed catboat at the Beetle Yard in Wareham, Massachusetts. Both jobs gave him a deep foundation in marine restoration and construction at the highest level. Living expenses on the Cape were high, though. Wanting all the things Maine had to offer—community, elbow room, and a great place to raise a family—he moved downeast with his wife and children. O’Donovan got a job at another top-notch boatshop, French and Webb in Belfast, which had recently received the contract to restore three Herreshoff Buzzards Bay 30s.

It was there that John O’Donovan met Patrick Dole and where they decided to hang out their own shingle, just up the road in Searsport. When the Ocean Pearl job came their way, it was a validation of the many decisions each had made over the course of their young lives.

Ocean Pearl’s restored pilothouse includes new systems and cabinetry while still retaining the vessel’s historic feel. Photo by George Nashan

Ocean Pearl’s restored pilothouse includes new systems and cabinetry while still retaining the vessel’s historic feel. Photo by George Nashan

Nigel Jagger, the Englishman who had purchased Ocean Pearl and committed himself to her rebuilding, was not only a connoisseur of wooden boats, he was an experienced owner employing an experienced captain, Ron Bessey, who would play a crucial role in overseeing the job. Because of their deep knowledge of projects like this, the ownership team and the shipwright team quickly established a mutual harmony.

The challenge Ocean Pearl presented was how to incorporate modern systems and an improved layout without destroying the magic of the boat’s historical look and feel. The results are stunningly beautiful. Complicated new machinery and circuitry panels are cleverly hidden. Most impressive of all, one simply cannot tell where Ocean Pearl’s original cabinetry and joinerwork leaves off and her restoration cabinetry begins.

When they decided to refurbish the Ocean Pearl in Maine, Nigel Jagger and his wife didn’t know a thing about the state or its coast. At her re-launching party, Nigel looked across the bright waters of Belfast harbor at Ocean Pearl swinging at a mooring. Thinking back over the people he had met here and now counted as friends, as well as the great work done on the boat he had grown to love, he expressed his appreciation of this place, even contemplating the possibility that heaven, if there is one, must be a lot like Maine.

To which I could only add: “Amen, Brother. Amen!”

Bill Mayher lives in Brooklin, Maine, and is one of the founders of the maritime web site offcenterharbor.com. Videos of both his project and Maynard Bray’s were shot by offcenterharbor.com’s filmmaker Steve Stone. They are available for viewing on the site.