Lyman-Morse expands to Camden

On a hot afternoon last July, Heidi and Cabot Lyman of Lyman-Morse, their son Drew, his wife MacKenzie, and their young children lined up behind a giant ribbon on the wharf at Wayfarer Marine in Camden, Maine. Wielding oversized scissors and broad grins, Drew and Cabot cut the ribbon to celebrate their company’s purchase of the Camden yard. The celebration was still going on this fall.

“We’ve gotten great support on this,” said Cabot Lyman. “We had a very good summer and it looks like we will have a good winter. We’re filling up fast with happy customers.”

Started by Cabot and Heidi Lyman in 1978, Thomaston-based Lyman-Morse has established itself as a quality service yard and boatbuilder. Recently the company has expanded into areas outside the marine world, working with the airline industry, the Department of Defense, and start-up projects such as solar power re-generating units and large-scale solar arrays. The Lymans are also completing a 26-room boutique hotel in Rockland, Maine.

The purchase of Wayfarer gives the company a foothold in Camden, which is known as a yachting Mecca.

“We are very excited about joining the two crews to create a most talented group of marine experts,” said Drew Lyman who has taken over from his father as president of Lyman-Morse. “Wayfarer’s customers will benefit in a big way through economies of scale and access to Lyman-Morse’s depth of expertise and resources including our boatbuilding pedigree, Lyman-Morse Fabrication, our CNC machining department, and Lyman-Morse Technologies.”

Wayfarer Marine and Camden have been a center of yachting in the northeast for more than 100 years. With 37 slips, and 846 feet of dockage, Wayfarer sits on 9+ acres along one side of Camden Harbor. The service yard is equipped with a 110-ton Travelift, an 80-ton Brownell trailer, and nine climate-controlled work and paint bays.

Illustration by Ted Walsh

Illustration by Ted Walsh

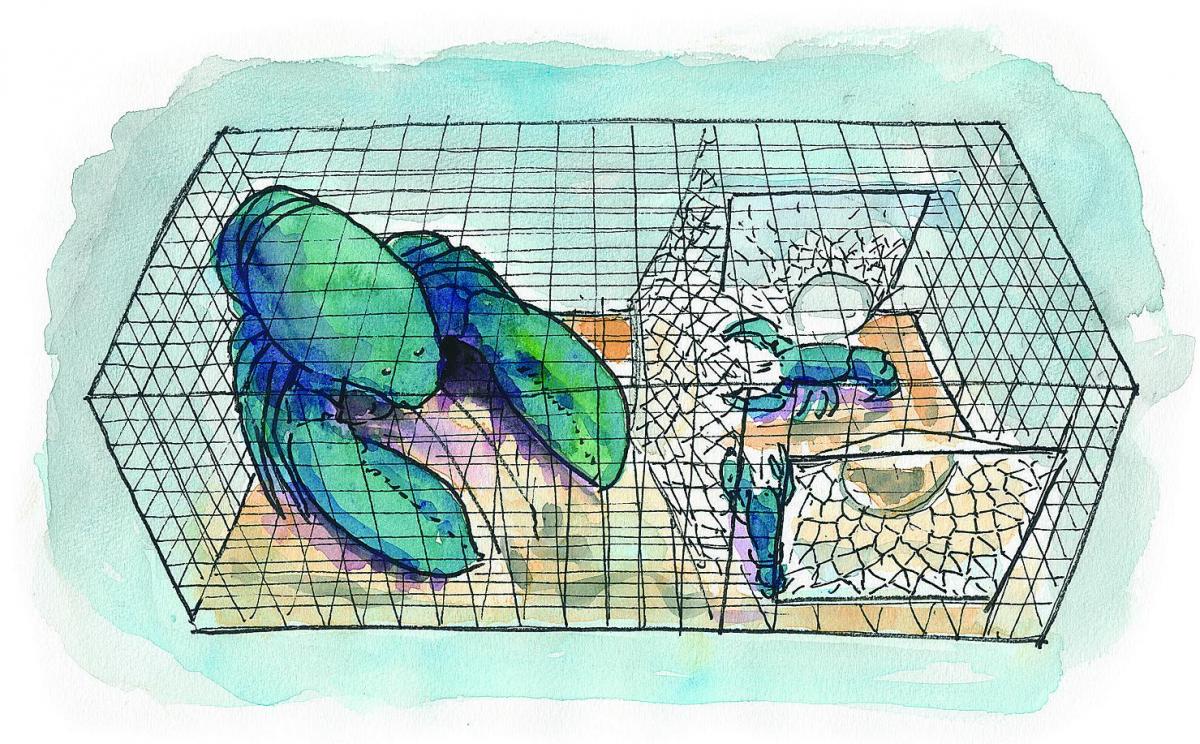

Monster lobster

When Ricky Louis Felice, Jr., a 24-year-old fisherman from Cushing, Maine, posted a photograph of himself holding a 3-foot-long, 20-pound crustacean on his Facebook page, he and his catch quickly became a media sensation.

Felice was working as a deckhand on the Big Dipper, a lobsterboat based in Friendship and captained by Isaac Lash, when the crew hauled up a trap with the behemoth cowering inside, according to a report in the Portland Press Herald.

“He was huddled over in the corner (of the trap), all balled up. Lobsters are very territorial and I don’t think he liked the fact that there were five lobsters inside the trap with him,” Felice told the newspaper. “His whole body was inside the trap. He was the biggest lobster I’ve ever seen in my life.”

The fishing crew threw the lobster back since Maine law prohibits keeping lobsters over a certain size. While the creature was the biggest Felice had ever seen, Lash told the newspaper he has seen larger ones.

According to the Maine Department of Marine Resources, the record for the largest documented lobster goes to one caught off the coast of Nova Scotia in 1977. It weighed 44 pounds, 6 ounces and was estimated to be 100 years old.

Beached basking shark dies

While we’re on the topic of giant creatures, we are sorry to report that volunteers with buckets of water were unable to save a 24-foot-long male basking shark that beached itself in Lubec in early September. A local clammer found the shark struggling on a sandbar, according to a report in the Quoddy Tides. A bucket brigade was formed to pour water on the shark’s gills, but it died before the tide came in sufficiently to allow it to be towed to safety. According to the newspaper’s story, there have been five sightings this year of basking sharks in the Bay of Fundy. Following its death the shark was towed out into the Lubec Channel where, the newspaper wrote, “it became part of the food chain.”

Sea of slime

Speaking of the food chain…. a friend was wading into the water to go swimming after a picnic lunch on a Midcoast island this past summer, when the sight of a gelatinous orange blob floating just below the surface quickly drove her back to shore. Apparently this sort of sighting has been more common lately, as the numbers of jellyfish lurking along the Maine coast have gone up.

Nick Record, a senior research scientist at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay has been trying to track the increase to better understand these complex ocean critters. In the absence of government funding for research, he has turned to citizen scientists. Starting in 2014, Record began asking members of the public who see jellyfish to email him reports, with photos if possible, of what they saw, when, and where. As of mid-September he had collected about 300 sightings, which he entered into a database and map. Go to his website to see some of the photos he has collected.

The three most common species of jellyfish sighted in Maine are moon (characterized by four small white circles), lion’s mane (mostly red), and whitecross (white cross on its back). Last summer saw an outbreak of lion’s manes in southern Maine. This summer’s biggest outbreak was whitecross jellyfish in the Bay of Fundy, where there were so many that they clogged fishing weirs. Just in case you’re wondering, apparently the lion’s mane has the most potent sting, but even that tends not to be severe, although Record says that a year ago one giant, 50-pound lion’s mane reportedly stung 100 swimmers in New Hampshire, causing some severe reactions.

Scientists do not know for sure the reasons behind the jellyfish explosion, but they have some ideas, said Record. “I call it the jelly ocean hypothesis. Some others call it the rise of slime. It’s a hypothesis, albeit one debated among scientists, that because of human-related causes we are shifting toward an ocean that will be dominated by jellyfish and other gelatinous species.”

Jellyfish thrive in warmer water—and the Gulf of Maine is warmer now than it has ever been. They also do well in water polluted by fertilizer run-off and grow well on human-built structures, and overfishing has removed many of their competitors.

Most species of jellyfish begin as slimy polyps attached to the sea floor or structures such as docks. When conditions are right these blobs send off clouds of small jellyfish clones—sometimes thousands at a time, Record said. He is hoping to learn more about why this happens.

“One of the things I have been really excited about with this project is seeing first hand the numbers of people with untapped knowledge. In light of cuts in government funding this is a neat way to do science.”

You can email him news of your jelly sightings at jellyfish@bigelow.org or tweet with the hashtag #mainejellies. Record’s jellyfish photo gallery is at https://www.bigelow.org/research/srs/nick-record/nick-record-laboratory….

Speedy ocean crossing

The Maine-built hi-tech racer Comanche, sailed by skipper Ken Read and a crew of 20, set a new monohull speed record during the July 2015 Transatlantic Race, fulfilling her owners’ wish that she be the fastest monohull in the world. Comanche, built at Hodgdon Yachts in East Boothbay and launched in 2014, averaged 25.75 knots, sailing 618.01 nautical miles in 24 hours. For the record, that is faster than MBH&H Publisher John Hanson’s powerboat!

The previous record was 24.85 knots set by Torben Grael and the Ericsson 4 VO70 crew during the 2008-2009 Volvo Ocean Race.

Comanche, a 100-foot supermaxi owned by Jim and Kristy Clark, sailed from Newport, Rhode Island, to Cowes, England, in a blistering seven and a half days, finishing second in her class behind George David’s Rambler and fifth overall. Interestingly the fastest multihull in the race only beat Comanche by nine hours.

Write a good essay, win a schooner

You’ve read about essay contests to win country inns, but what about a contest to win a boat, a really big boat?

Brenda Thomas, captain and owner of the schooner Isaac Evans in Rockland, Maine, decided she wanted to spend more time on land, but instead of putting her 65-foot vessel on the market, she held an essay contest.

After 21 seasons on board the Evans, and 17 seasons as owner, Thomas announced last summer that she planned to award the schooner to the writer of a 200-word essay that best addresses the theme “Why I would like to own the Maine Windjammer Isaac H. Evans.”

Designated as a National Historic Landmark, the 65-foot long schooner was built in 1886 in New Jersey for oyster fishing in Delaware Bay. She was brought to Maine in the 1970s and rebuilt for the passenger schooner business in 1973. The Evans, which takes passengers on overnight cruises as well as day sails out of Rockland, Maine, has berths for 22 passengers.

Essay contestants had to pay a $125 entry fee. Thomas planned to select the top 20 essays and turn them over to two impartial judges for selection of a winner and two runners-up. The deadline for essays was October 31. Thomas hoped to choose a winner by December 1. Tune in next issue to learn who won.

Love, not war, for this frigate

The massive French frigate L’Hermione showed up on computer screens in Maine before anyone saw the actual vessel. As L’Hermione headed to Castine, Maine, on July 14, mariners around Penobscot Bay followed her progress on various maritime tracking web sites. A thick fog had settled in and while the ship is big—153 LOA, with a beam of 36 feet and masts reaching up to 185 feet—even L’Hermione was hard to find in the swirling mist. Then, as the midday sun burned through the fog, the frigate was revealed, complete with 34 guns, 1,000 blocks, 15 miles of cordage, and 35,000 square feet of sail. It was easy to imagine how such a sight might have terrified the opposing fleet during the American Revolution when the original L’Hermione brought the Marquis de Lafayette to this fledgling country with his promise of French support.

The exact replica that visited Maine took more than 15 years to build in Rochefort, France. A crew sailed her across the Atlantic in the spring of 2015, taking 27 days for the crossing (compared to the original vessel’s 38-day voyage). L’Hermione then visited 11 East Coast ports, including Washington D.C, Philadelphia, Newport, and Boston, before arriving in Maine.

The original L’Hermione visited Castine in the summer of 1780 to spy on the British after dropping Lafayette off in Boston. This time around, the coastal community had organized a rousing welcome and two days of celebration, including a welcoming parade with a small replica of the replica carried by children, and plenty of speeches.

New leader at Morris

Morris Yachts, a Maine-based builder of high-end sailing yachts from 29 to 80 feet, has hired a former Coast Guard officer and top dinghy sailor as its new leader. Pete Carroll is now responsible for all aspects of operations, customer service, finance, and facilities.

A native of Fort Collins, Colorado, Carroll recently retired from the U.S. Coast Guard after 20 years of active duty, completing his position as commanding officer of the Civil Engineering Unit Cleveland. He holds Master’s degrees in science and engineering from the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana, as well as in business administration from the University of Michigan. While Carroll was obtaining his undergraduate education at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, he was a member of the Coast Guard Dinghy Racing Team; he and his sailing partner won the freshman dinghy nationals. While serving aboard the USCGC Reliance out of Kittery, Maine, he earned the equivalent to a first mate license for vessels less than 800 tons.

Carroll has strong Maine ties. He spent summers at his family’s cottage in Southwest Harbor since the age of two. He and his family are long-time friends of the Morris family and Carroll and his wife Rebecca, and their two children Mia and Wyatt, have made Mount Desert Island their full-time home.