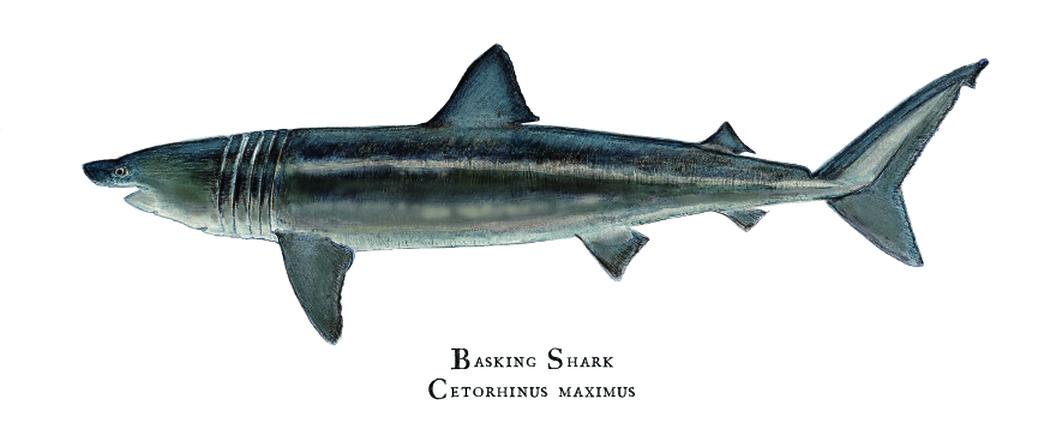

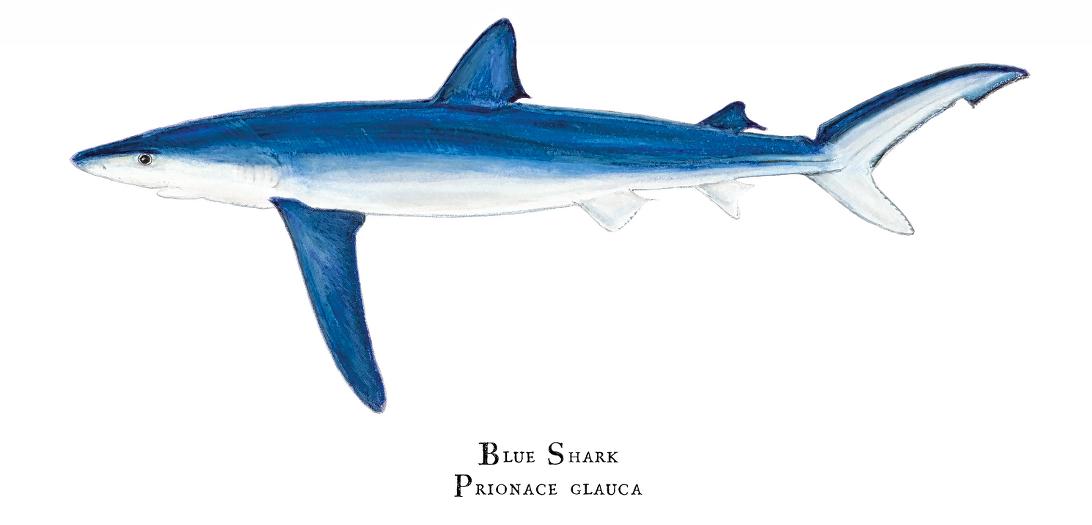

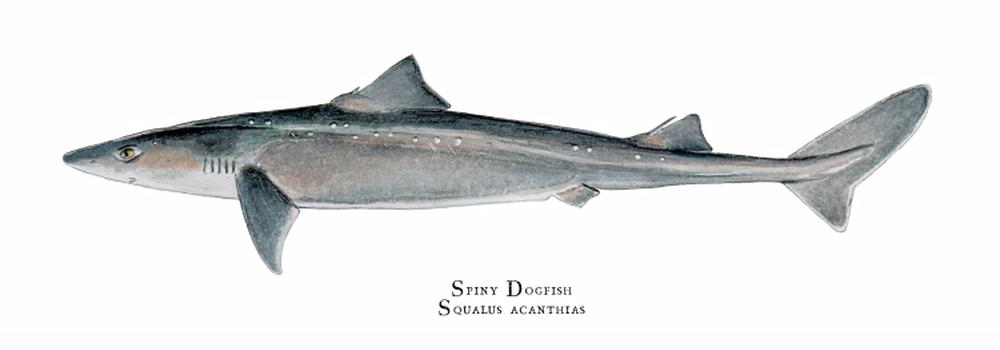

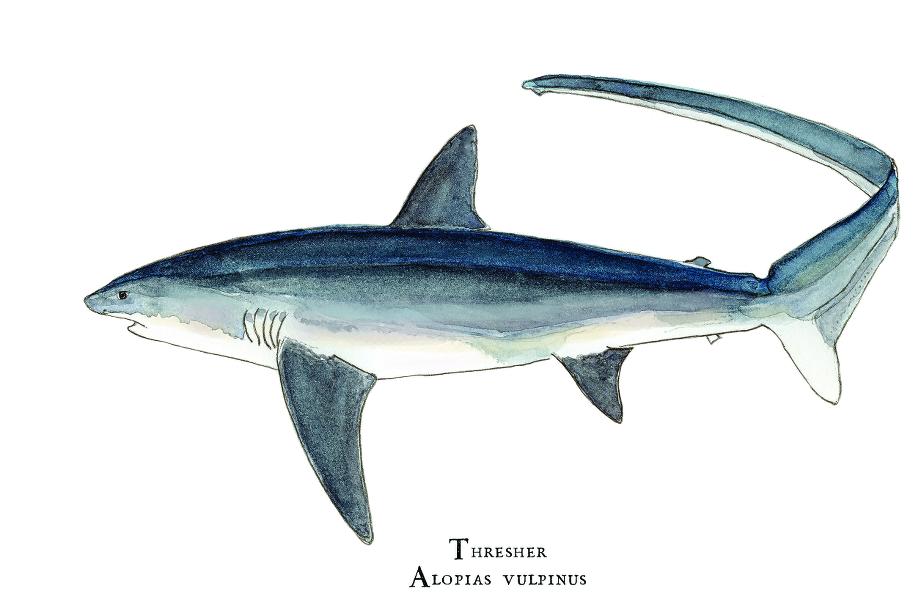

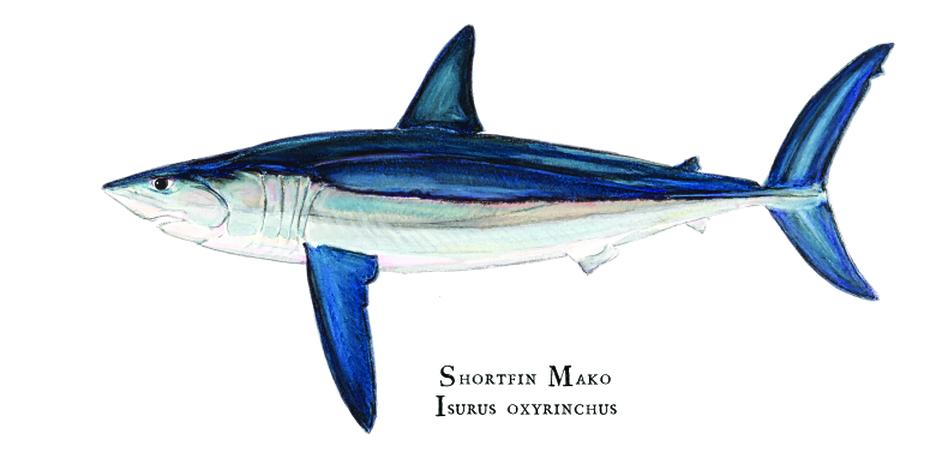

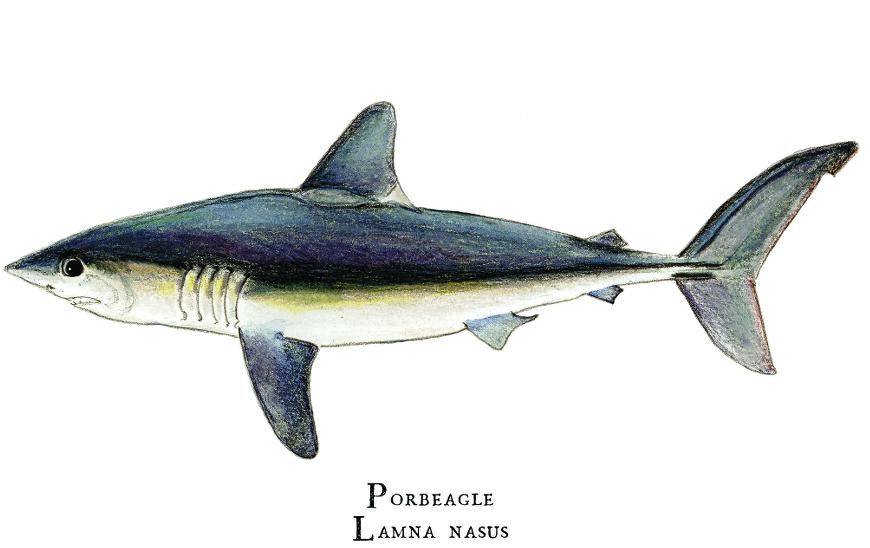

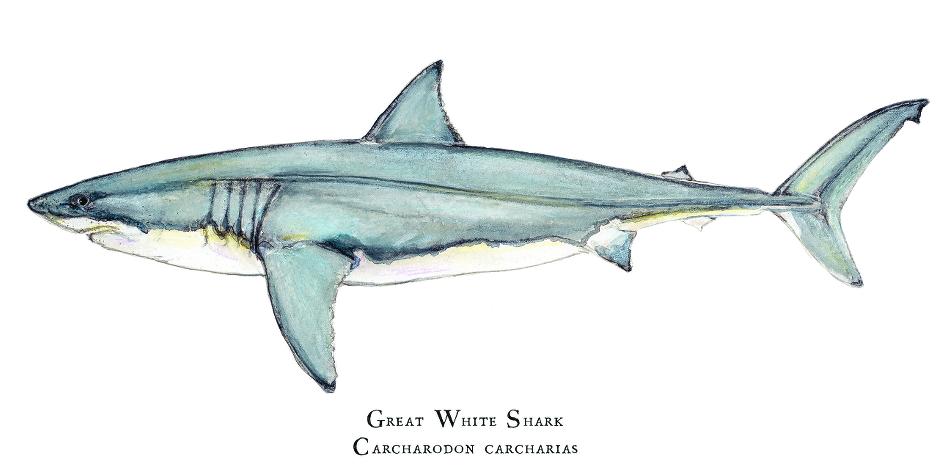

Illustrations by Karen Talbot

It’s one of those days on the coast of Maine—brilliant skies punctuated by a handful of arrestingly white cumulus clouds that cast summer shadows upon a swath of open ocean. It’s one of those days when being on a boat is compulsory, at least that’s the likely narrative on the decks of many vessels heading out from harbors and coves from Kittery to Lubec. Some of those setting sail, like Dr. James Sulikowski, might be going fishing, but few are focused solely on a single poorly understood and oft-maligned yet wildly popular group of marine animals. Most are not fishing exclusively for sharks with the intent of tagging and releasing them in the name of science, something Sulikowski has been doing from his base on the Saco River for the past six years as part of his ongoing research.

“When people think of Maine,” said Sulikowski, “they don’t really think of sharks, but our waters are pretty sharky.” Sulikowski is a professor at the University of New England in Biddeford. Dubbed “Dr. Shark” in the media, he has studied sharks worldwide.

The Gulf of Maine is a sea within a sea, snugged up against northern New England and reaching into the Canadian Maritime Provinces like a large animal. To the south, its tail is cradled by Cape Cod. Its backbone extends downeast to an outstretched neck and snout called the Bay of Fundy. The underbelly—the southeastern extent of the gulf—bulges from the tip of Nova Scotia to the light at Chatham, Massachusetts.

Dr. James Sulikowski, center, and students with a baby porbeagle in the Gulf. Photo by Cameron HodgdonIt covers an area of more than 69,000 square miles, and, according to Sulikowski, the Gulf asks “big dynamic questions.” Some of the biggest questions concern the region’s largest predators—sharks. Like many other marine ecosystems, the Gulf of Maine depends in part on top predators like sharks for its health, and there are eight sharks documented in the Gulf. Boaters and anglers most commonly encounter blue sharks, basking sharks and spiny dogfish, while diners at coastal restaurants may recognize the two species most often landed commercially—thresher and shortfin mako. The final three species are the porbeagle, sand tiger shark, and the great white shark. “These last three are the ones we are most concerned about,” said Sulikowski.

Dr. James Sulikowski, center, and students with a baby porbeagle in the Gulf. Photo by Cameron HodgdonIt covers an area of more than 69,000 square miles, and, according to Sulikowski, the Gulf asks “big dynamic questions.” Some of the biggest questions concern the region’s largest predators—sharks. Like many other marine ecosystems, the Gulf of Maine depends in part on top predators like sharks for its health, and there are eight sharks documented in the Gulf. Boaters and anglers most commonly encounter blue sharks, basking sharks and spiny dogfish, while diners at coastal restaurants may recognize the two species most often landed commercially—thresher and shortfin mako. The final three species are the porbeagle, sand tiger shark, and the great white shark. “These last three are the ones we are most concerned about,” said Sulikowski.

Sharks are in trouble—that’s the message from a bevy of conservation groups and ocean advocacy organizations. “According to the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature] Red List, approximately 75 percent of all sharks, skates, and rays are threatened, or lacking sufficient data necessary for proper management,” said Sulikowski. Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing is a global problem for sharks. While shark-finning gets the air time, there are also concerns with commercial fishing, where shark bycatch and secondary target catch threaten populations of these highly migratory and remarkably vulnerable animals about which we have so little data.

“It’s pretty sad,” said Sulikowski about the paucity of shark data. “The collection of information such as movement patterns, growth rates, reproductive biology, and resiliency to stress are crucial to the successful management of any fish species. Obtaining this knowledge becomes even more important for organisms, like many sharks, that have slow rates of growth, low fecundity [the inability to produce abundant offspring], and are more susceptible to environmental stressors.”

Sulikowski said that all the Gulf of Maine species, except the dogfish, are ones we know very little about biologically. “As such,” he said, “We have to protect their populations.” We have to learn more.

The two most common sharks in the Gulf of Maine, the spiny dogfish and the blue shark, are likely the only two with stable populations. Of the eight shark species found in the Gulf, the basking, mako, sand, thresher, and great white sharks are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. The blue shark is listed as near threatened. While the porbeagle and spiny dogfish are overall listed as vulnerable, their populations in our waters are considered endangered.

The reason so many sharks are listed as vulnerable or threatened is because most share common life history and reproductive traits. While there are exceptions, many sharks are slow to grow and slow to reach sexual maturity. Most have a lengthy gestation period and produce few offspring. This, combined with fishing pressure, makes it difficult for sharks to maintain stable populations.

Growing to a reported maximum size of more than 49 feet, the basking shark is the largest of the Gulf of Maine sharks and the second-largest living fish, behind the whale shark. Its scientific name, Cetorhinus maximus, translates as something akin to “largest marine monster,” but Sulikowski said these magnificent animals are far from monsters. “They’re big,” he said, “but they’re filter feeders and pose no threat.” Basking sharks are one of only three filter-feeding sharks that feed on plankton. People commonly misidentify them as great white sharks because of their size and the shape of their dorsal fin. Key differences include larger gills on the basking shark and its lack of large teeth. Centuries of exploitation for liver oil, food, fins, and fishmeal, combined with life history and reproductive traits, put the basking shark near the top of some scientists’ species of concern list. One of the reasons basking sharks are more familiar to gulf boaters despite their relative rarity is because they are so big and they “bask” on the surface, although they are also capable of deep dives.

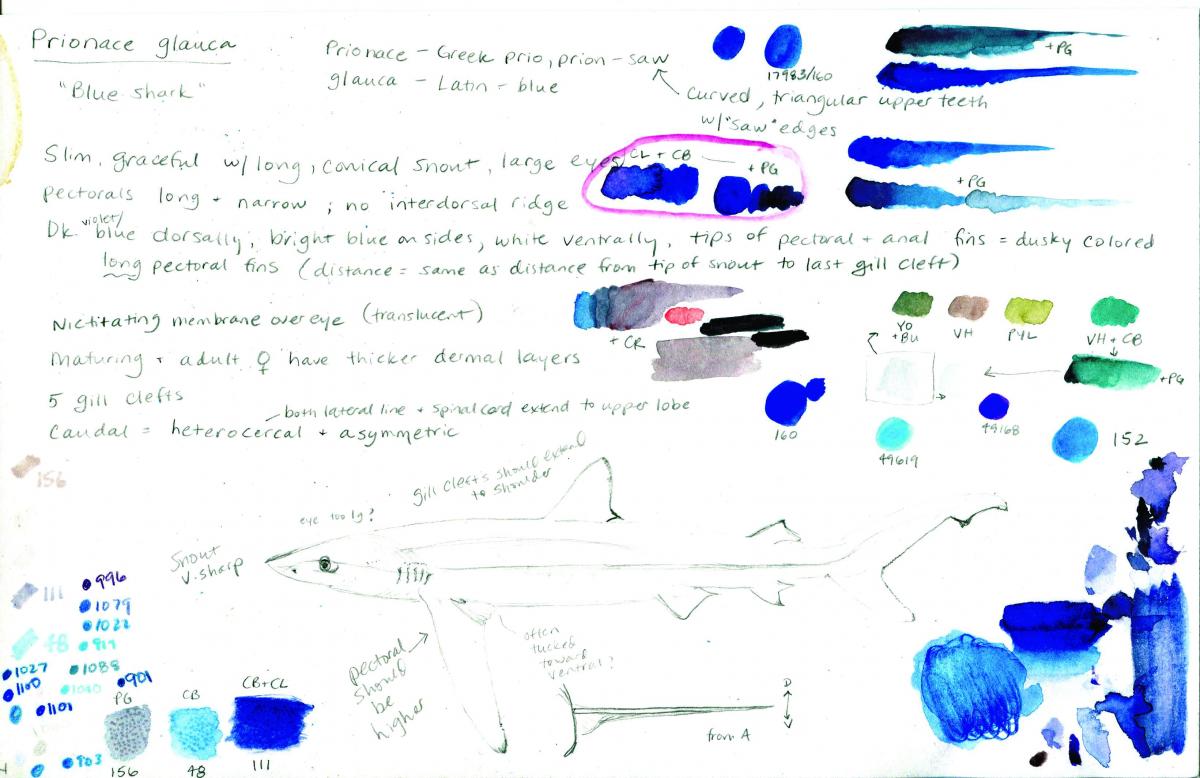

The blue shark reaches a maximum size of 13 feet or so. Unlike the basking shark, the blue shark is considered abundant. It grows relatively quickly, reaches maturity in as little as four years and produces litters of up to 80 pups (more commonly less than 40). While the blue shark is a keystone predator essential to ecosystem health, there is little evidence to suggest significant population decline despite an estimated 10 million to 20 million taken annually in fisheries worldwide. Its scientific name, Prionace glauca, translates to “blue saw” because of its brilliant color and the serrations on the edges of this shark’s teeth.

Reaching a length of just four feet, the spiny dogfish is diminutive in size and controversial. This scrappy predator has seen dramatic swings in its population largely due to supply and demand issues and poor management. At one point, when exports of dogfish were high, the species was over-fished. Recently populations have rebounded to such an extent that the species is considered abundant and is often blamed for fouling fishing gear and preying on more valuable food fish species such as cod. The scientific name, Squalus acanthias, alludes to two venomous spines, one at the anterior side of each dorsal fin. Many have pushed to increase the commercial fishery and domestic consumption of dogfish. Consumers have been slow to catch on, though, because of lack of familiarity and availability, as well as concerns about mercury.

Like most long-lived, top predators, sharks tend to be high in mercury, which bioaccumulates as it moves up the food chain. For that reason,the FDA advises women of reproductive age and young children not to eat any shark. Everyone else should limit consumption to avoid health concerns.

That said, the most common sharks found on plates in Maine are the thresher and the shortfin mako, according to Sulikowski. The thresher shark is big, reaching a maximum size of close to 25 feet. It is one of three sharks from the genus Alopias, meaning fox—a nod to the upper lobe of its tailfin, which can be as long as the fish’s body. Commonly called the common thresher, the fox shark, or the swiveltail, this shark uses its tail to stun schooling fishes and other prey.

The other shark species commonly seen in restaurants and at the fishmonger’s is the shortfin mako. The shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus, which means equal tail) reaches a maximum length of 13 feet and can weigh 1,200 pounds. In addition to target fisheries, mako sharks are often harvested as bycatch in longline and driftnet fisheries (especially tuna fisheries). This is one of the fastest, if not the fastest, sharks known and is capable of bursts of speed over 30 mph.

Sulikowski expressed the most concern for porbeagle, sand tiger, and white sharks in the gulf. Of these three, some of the most interesting current research concerns the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus), which can attain a length of about 11 feet. Population declines are attributed to the combined factors of low reproductive capacity and moderate to heavy fishing pressure. Porbeagle populations in the north Atlantic were severely affected by directed longline fisheries. Like many shark species, data on the physiological and behavioral ecology of porbeagles is lacking, but Sulikowski now believes the Gulf of Maine may be a critical nursery for this oceanic shark species. The origins of the common name porbeagle are unclear but may be a blending of the words porpoise and beagle, alluding to this shark’s strong hunting prowess.

Sand tiger sharks (Carcharias taurus), also called grey nurse sharks, can reach a maximum length of 11 feet. These coastal sharks are rare in the gulf, according to Sulikowski. The species is unique among sharks insofar as it is believed to be the only shark that can inhale and store air in its stomach in order to maintain neutral buoyancy. At least one study suggests that sand tiger shark populations declined by as much as 75 percent during the 1980s as a result of the commercial shark fishery along the Atlantic coast.

Like the sand tiger shark, the white shark, commonly referred to as the great white shark, is rare in the Gulf of Maine. While not as big as the basking shark, the white shark can reach almost 20 feet (maybe larger). Also like the basking shark, the scientific name, Carcharodon carcharias, alludes to people’s fear of the species and translates roughly to “sharp tooth man-eater.” White sharks, which actually are lead-grey to brown or black above, lighter on the sides, and white below, have hundreds of sharp teeth in several rows and weigh up to 5,000 pounds. While they currently are rare in the gulf, some shark experts believe more whites will move into the region as populations of prey species like seals expand.

While the white shark gets a lot of attention in the popular media, it is a baby porbeagle that has Sulikowski’s attention on this gorgeous summer day. His research is unlocking the secrets of this species itself, as well as helping scientists to better understand the Gulf of Maine as an ecosystem and its role in the north Atlantic. As of this writing he and his students have captured two baby sharks. So far this year they have attached a satellite tag (and drawn a blood sample) from one porbeagle.

“This type of technology, although expensive at $4,200 per tag, has never been used on such a little shark before,” he said. “It will allow us to learn vital ecological information that will ultimately help in the conservation efforts for this species.”

As he heads back up the Saco River to a mooring by Camp Ellis, Sulikowski is thinking about the next shark he will tag and what additional secrets will be revealed about these mysterious creatures.

Ret Talbot is an award-winning freelance journalist who covers fisheries at the intersection of science and sustainability. He lives in Rockland, Maine.

Great White Sharks in Maine

The movie Jaws came out in 1975 when I was a teenager. Yes, I understood that the great white on the screen was a mechanical model, and that real sharks do not behave like Peter Benchley’s fictional man-chasing monster. But that did not stop me from imagining all sorts of dire consequences each time I jumped off the dock to go swimming in North Haven, Maine, where my family spent summers.

Especially because I had inside information. I knew there really were great white sharks out there. My uncle, Lincoln Davis, had harpooned one in the late 1950s just off the Drunkard Ledge at the western entrance of the Fox Islands Thorofare. He was heading to Rockland on a boat with his father (my grandfather) when they saw the shark’s fin cutting through the flat calm water.

Harry Goodridge killed this great white shark and cut it open after it ate his pet seal, Basil. His next seal, Andre, became famous in Rockport, Maine, and elsewhere as the subject of books and a movie. Today, there is a statue of Andre near where this photo was taken.

Harry Goodridge killed this great white shark and cut it open after it ate his pet seal, Basil. His next seal, Andre, became famous in Rockport, Maine, and elsewhere as the subject of books and a movie. Today, there is a statue of Andre near where this photo was taken.“The old man said ‘you go and harpoon it,’” recalled Davis, who was 13 at the time. “My harpoon broke its back and the shark leapt clean out of the water.”

They took the dead shark, which was about 13 feet long, to Hopkins Wharf on North Haven, where they cut it open, finding a couple of seals and a big halibut in its belly. They ate the meat, which tasted like swordfish, said Davis, who now owns Stetson and Pinkham outboard engine repair in Waldoboro.

Back in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Penobscot Bay fishermen often saw great white sharks. Some speculate that they were attracted by bloody chicken parts, dumped into the bay by the poultry plant in Belfast.

Off Rockport in 1959 and 1960, then harbormaster Harry Goodridge harpooned several great whites, including a 12-footer that had eaten his pet seal Basil.

Harry liked to go shark fishing on calm days when he could see the fins more easily, recalled his daughter, Carol. An avid hunter and fisherman, he always had a harpoon with a bucket of line, just in case. One summer day Harry was fishing out by Robinson Rock, accompanied by Basil. He noticed blood on the water about the same time he realized that Basil had gone swimming over the side, Carol remembered. Then he saw the shark fin. Harry harpooned the shark and towed it into Rockport where he cut it open and found Basil in three pieces, she said. Goodridge sold the shark meat to Yorkie’s Diner in Camden, which put it on the menu where it quickly sold out. Harry made pendants out of the teeth for his family. Carol still has hers.

“It was a very sad and gruesome lesson for my father not to take a baby seal out with him in an open boat while hunting for sharks,” she said.

Soon afterward the Goodridge family adopted a young seal that they named Andre—the subject of both a book and a movie.

As for me, I got over my Jaws-induced shark phobia quite a long time ago. Then word came during the last few years that fishermen have once again been seeing great whites along the Maine coast. A college classmate was actually bitten by one while swimming off a beach on Cape Cod (he survived).

Biologists assure me the chances of being attacked while swimming off a beach in Maine are slim and I believe them. So I will go back in the water and you should, too.

Just be careful.

—By Polly Saltonstall

The Artist Behind the Illustrations

Karen Talbot is an award-winning conservation artist known primarily for her lifelike, fine art paintings and scientific illustrations of fishes, birds, and botanicals.

Karen Talbot is an award-winning conservation artist known primarily for her lifelike, fine art paintings and scientific illustrations of fishes, birds, and botanicals.

These shark images were painted specifically for this article. As she does with all of her work, Talbot carefully researched each species to understand its place in the ecosystem as well as its special characteristics. She frequently works with specimens of her subjects, counting scales and measuring proportions, sometimes even dissecting them, in order to make her work as scientifically accurate as possible.

Amazingly, she is mostly self-taught, working as a school teacher for 16 years before finally turning her lifelong love of drawing into a profession.

Talbot’s grandmother was an artist who specialized in landscapes and her mother was a devoted bird watcher, giving her exposure as a child to both art and science. She loved to draw, but kept her work private for a long time. Then in 2009, she decided to exhibit some of her work in a local art festival in Laguna Beach, California, where she and her husband were living at the time. “I was terrified but I did it and it was great. I got so busy, I was turning away work,” she said.

In 2011, Talbot gave up teaching to become a full-time artist. When she and her husband, Ret Talbot, who is a writer, moved to Rockland, Maine, from California in 2012, Karen opened a gallery and studio attached to her home.

She has done commissions for museums, books, and magazines, taking inspiration from oceans, streams, canyons, and mountains where she regularly dives, fishes, and climbs. To see more of Talbot’s work, go to www.karentalbotart.com. She also will be an exhibitor at the 2015 Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors Show (Aug. 14-16) in Rockland, Maine.

This blue shark study reveals Talbot’s research process prior to painting, as she gathers scientific facts and measurements and identifies the color palette.

This blue shark study reveals Talbot’s research process prior to painting, as she gathers scientific facts and measurements and identifies the color palette.