Loons raise themselves up out of the water in a ballet-like performance while courting a mate, preening, or when threatened during territorial disputes. Photo by Kittie Wilson. In the 1981 film On Golden Pond, Katherine Hepburn’s character doesn’t share her excitement with her husband when they arrive back to their cottage on Golden Pond by saying, “oh, Norman, the geese,” or “oh Norman, the ducks.” Rather, she says, “oh, Norman, THE LOONS,” and for good reason. While geese and ducks have their charm, they simply do not embody the soul of a New England lake the way loons do.

Loons raise themselves up out of the water in a ballet-like performance while courting a mate, preening, or when threatened during territorial disputes. Photo by Kittie Wilson. In the 1981 film On Golden Pond, Katherine Hepburn’s character doesn’t share her excitement with her husband when they arrive back to their cottage on Golden Pond by saying, “oh, Norman, the geese,” or “oh Norman, the ducks.” Rather, she says, “oh, Norman, THE LOONS,” and for good reason. While geese and ducks have their charm, they simply do not embody the soul of a New England lake the way loons do.

Loons are a triple-threat in the bird world: they are stunning to look at, possess a supernatural voice, and are skilled predators of fish. Most of our views of loons are at a great distance (which is good for loons, as they shun human activity). But up close male and female adult loons are striking, with a velvety, blackish green head, bright red eyes, a sleek torpedo-shaped body, black-and-white checkered back, and a harpoon of a bill capable of skewering fish at a depth of 200 feet. Young loons and adults in winter are ash-gray overall, hence their Latin name, Gavia immer (immer is Latin for ashes).

Loons convey an incredible sense of place. This isn’t surprising given that the world’s five species of loons have been adapting to freshwater lakes for nearly 40 million years. Loons are one of the great survival stories in the natural world—only ducks and pheasants appear earlier in the fossil record of North America.

Ask any realtor how to find a great cottage on a lake and they will tell you, location, location, and location. Ask an ornithologist the same question and they will tell you, loons, loons, and loons. Don’t bother with the number of beds or baths; simply ask if the lake has a loon. If the answer is yes, rest assured. Loons on a lake means the lake is quiet, that it hasn’t been overdeveloped, that it has neighbors who value natural resources, and that the water is clear, clean, and has abundant fish. What else do you need to know?

The first time I heard a loon call, I had just arrived to spend the summer at the Lake Itasca Biological Station in northern Minnesota and was lying in my bunk listening to these wild sounds and wondering what was making them. The fantastical calls seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere simultaneously.

Vocalizing is exceedingly important at every stage of a loon’s life. Loons have four distinct calls. The tremolo is characterized by a short, wavering quality used to signal distress or alarm at territorial disputes with other loons, or with people. The yodel is a long and complex call made only by male loons to establish territorial boundaries. The wail, a long call consisting of up to three notes, is reminiscent of a wolf’s howl. Typically breeding adults and chicks wail in duet, back and forth, as a way of maintaining contact. Lastly, the hoot is a short, softer, more intimate call that, like the wail, functions to maintain contact, but exclusively within loon family groups.

In the summer, loons are distributed on lakes throughout Maine, but are concentrated in the north. They prefer fish-bearing lakes with clear, warm, shallow water, and little human activity. Loon lakes are usually at least a quarter mile long—the takeoff distance required by loons to get airborne. Loons will build a shallow grass nest within the vegetation at the edge of lake islands and along lakeshores. They will also use artificial floating nests when provided. In the winter, habitats include inland freshwater lakes and rivers, as well as marine bays, coves, channels, and inlets as far south as the Florida Keys.

Man-made floating nests have been a key tool in promoting loon survival, as they are not affected by the frequent changes in water level on many lakes that can flood and destroy nests on the ground. Loon eggs incubate for 30 to 32 days. Photo by Jonathan Fiely, courtesy Biodiversity Research Institute Maine Audubon’s Maine Loon Project monitors loons on Maine’s lakes. The project’s 2014 estimates put the population of loons in the state at about 4,000 adults. However, only about 250 new chicks were produced last summer. While the adult population is large and has been stable in Maine for 20 years, this low rate of reproduction is worrisome.

Man-made floating nests have been a key tool in promoting loon survival, as they are not affected by the frequent changes in water level on many lakes that can flood and destroy nests on the ground. Loon eggs incubate for 30 to 32 days. Photo by Jonathan Fiely, courtesy Biodiversity Research Institute Maine Audubon’s Maine Loon Project monitors loons on Maine’s lakes. The project’s 2014 estimates put the population of loons in the state at about 4,000 adults. However, only about 250 new chicks were produced last summer. While the adult population is large and has been stable in Maine for 20 years, this low rate of reproduction is worrisome.

Loons face many threats, some old and some new. Lead poisoning from ingesting lead fishing sinkers is, unfortunately, the leading cause of death among adult loons in this state. Lead is not a direct cause of death for loon chicks, but chicks that lose a parent to lead poisoning have a lower survival rate. New threats to Maine’s loons include an increase in extreme rain events (hypothesized to be caused by climate change), an increase in nest and egg predators such as raccoons, skunks and foxes, and the inundation of nests by careless boaters. Many lake residents have also been reporting a dramatic up-tick in bald eagle predation on both young and old loons, which is commensurate with the dramatic increase in eagle numbers statewide.

Ask anyone who has seen the movie On Golden Pond what they remember most. My guess is that they won’t remember that both Katherine Hepburn and Henry Fonda won Academy Awards or that Jane Fonda was nominated for one. Instead what they invariably remember is… the loons.

Richard Harris Podolsky is an ornithologist living in Rockport, Maine. He wrote an article on the razorbill auk for the inaugural issue of this

publication.

Photo by Daniel Poleschook, courtesy Biodiversity Research Institute

Photo by Daniel Poleschook, courtesy Biodiversity Research Institute

Loon lore

Since their legs are short and set far back, loons cannot walk well and are flightless on land. To take flight, loons may “run” as far as a quarter of a mile on the water’s surface to build enough speed to get airborne. In the air, they can fly up to 75 miles per hour.

The large webbed feet of loons act as propellers, enabling fast travel underwater. The record diving time for the common loon is three minutes. The average diving time is 42 seconds.

Loons weigh between 6 and 12 pounds and sit quite low in the water because their bones are solid and thus heavier than the hollow bones of other waterbirds.

Loons are excellent divers and can vanish underwater to find food or escape danger without leaving a ripple on the surface. Watch carefully and you may see that loons exhale and thereby slim down just before they take a dive.

Loons are sexually mature at age three and, on average, obtain their own breeding territory around age five. The female usually lays two eggs and both parents incubate them for 30 to 32 days.

Loon chicks are semi-precocial; they leave the nest within two days of hatch, locomoting behind the adults or riding on their parents’ backs. The parents do feed them nearly exclusively for the first eight weeks.

By early November before Maine lakes freeze, loons fly south to coastal seas, with some traveling 3,800 miles. Loons are one of the few birds found in both fresh water and salt water, from northern lakes to southern marine environments.

Those lucky enough to live on or near a loon lake can protect loons by following these recommendations:

- If you encounter an active loon nest, back away and observe with binoculars from a distance of at least 200 feet.

- Never discard fishing line in the water, to avoid entangling a loon.

- Obey the no-wake law within 200 feet of any shore where loons are nesting.

- Avoid using fertilizer and pesticides, which can run off into lakes.

- Plant shrubs along lakeshores to reduce potentially harmful runoff.

- Support loon and lake conservation projects such as the

- Maine Loon Project through Maine Audubon or the Biodiversity

- Research Institute’s Center for Loon Conservation.

The Biodiversity Research Institute

Maine’s Biodiversity Research Institute runs the Center for Loon Conservation, which is dedicated to assessing current and emerging threats to loons, and to collaborating with other organizations to conserve loon populations. The center also works with government agencies to monitor loons and study ecological stress factors such as loss of breeding habitat and exposure to mercury, lead, and oil.

Maine’s Biodiversity Research Institute runs the Center for Loon Conservation, which is dedicated to assessing current and emerging threats to loons, and to collaborating with other organizations to conserve loon populations. The center also works with government agencies to monitor loons and study ecological stress factors such as loss of breeding habitat and exposure to mercury, lead, and oil.

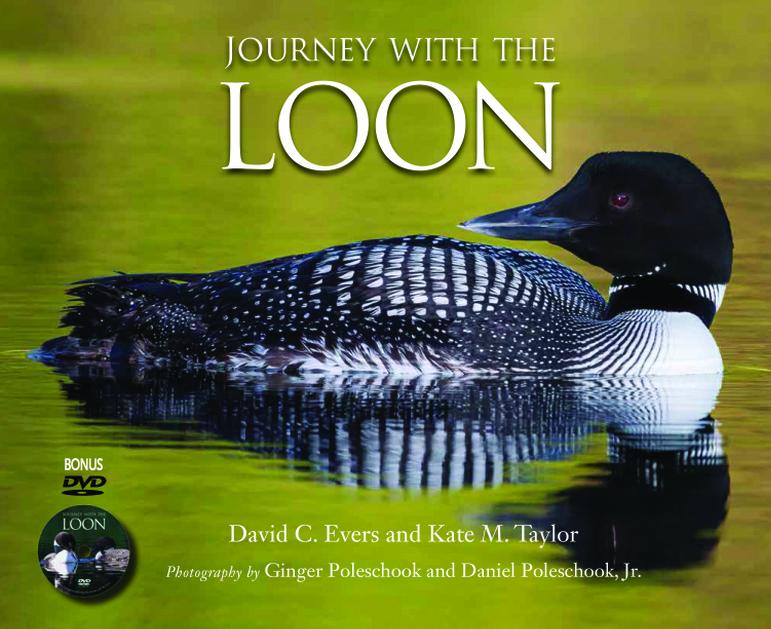

In 2014, BRI founders and leading experts on loon biology, Kate Taylor and David C. Evers, wrote a lovely coffee table book about loons, published by Willow Creek Press. The book includes stunning photos by Ginger and Daniel Poleschook, and explains the life cycle of these beautiful wild birds.

Sales of the book benefit BRI’s loon research. Copies can be ordered directly from BRI’s online bookstore at www.briwildfeathers.org.

BRI also operates loon cams in several lake locations. Check their website at www.briloon.org to see if the cameras are up and running.