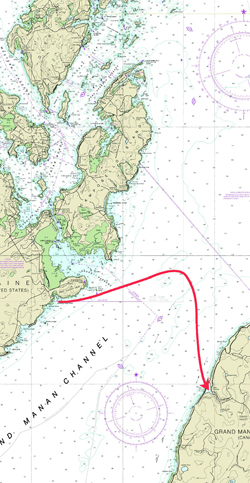

Photo courtesy Charles Legris. As Paul Moyneaux and Adam looked across the rough water between them and the cliff’s of Grand Manan, they wondered about the plan to row across in Paul’s Amesbury skiff. They went ahead, even though the tide carried them off course. The 10-mile crossing took seven hours.

Photo courtesy Charles Legris. As Paul Moyneaux and Adam looked across the rough water between them and the cliff’s of Grand Manan, they wondered about the plan to row across in Paul’s Amesbury skiff. They went ahead, even though the tide carried them off course. The 10-mile crossing took seven hours.

By Paul Molyneaux

They put in at Carrying Place Cove

and ended the trip at Dark Harbor.

The tide pushed them down the

channel as they went.

They put in at Carrying Place Cove

and ended the trip at Dark Harbor.

The tide pushed them down the

channel as they went.

The waves, now topping five feet, and steep, hid us from each other as we pulled for all we were worth.

Finally Steve dug his oars in. “Let’s just go,” he said as he leaned back into a powerful stroke. We were off, pulling for the far shore, Dark Harbor—the only refuge among the hundred-foot cliffs that guarded the western side of Grand Manan.

I thought that with our narrow boat we’d pull ahead of Charles and his gang, but with three in their boat, they took turns rowing and resting. Adam and I only had each other. The first couple of miles went okay. We held to our bearing as the flood tide swept us deep into Canadian waters, almost to The Wolves, a group of uninhabited islands between Grand Manan and the mainland. Adam and I soon got into a debate over the name of the island.

“They say it’s some bastardization of a Passamaquoddy word, but think about it,” I said. “The sailors who mapped this coast came from Brittany, a Celtic land, and the Celtic god of the sea is Mananan MacLear.”

Adam said the name Grand Manan was based on a Passamaquoddy word: Mun-a-nook, because someone he trusted more than me had told him so.

“Well then,” I said. “Mananan had a son, Mongan, as in Monhegan, don’t you think that’s a bit too coincidental?”

“I think you make up facts as you need them. Those sound like Native American names to me, not Irish.”

“Celtic.”

On we went. Charles and his crew were a quarter mile ahead of us as we hit the middle of the channel. The waves grew higher and higher and we pulled onward, our oars often catching in the rough water. We banged our blades together more often than we would have liked. Every time our bow dropped down off a wave it left just inches of freeboard to spare.

At one point a splash soaked my back.

“Did that come off your oar?” I asked Adam.

“No. Should I bail?”The waves grew higher and higher and we pulled onward, our oars often catching in the rough water. We banged our blades together more often than we would have liked.

“Might be a good idea.” When I looked over my shoulder I could see Charles’s boat atop a wave and then it disappeared into a trough. The waves, now topping five feet, and steep, hid us from each other as we pulled for all we were worth.

Adam bailed a bit and then manned his oars again.

“I wish Charles would let us catch up,” I said. “It’d be hard to help us if we swamp.”

“What should we do?” Adam asked.

“If we swamp? Stay with the boat. I brought a survival suit.”

“For me?”

I gave him an unsympathetic look.

“For me?” he said again.

“Well, you can try to get into it,” I said, relenting. “I brought a wet suit top, too. But the water’s so cold, 40-some degrees at most. We’d be hypothermic by the time Charles got to us.”

Adam started singing a song. I couldn’t make out the words, some other language.

“What are you singing?”

“The Mi’kmaq friendship song,” he said.

“Where’d you get that one?”

“I learned it at summer camp, from Chief Red Thunder Cloud. Do you want to learn it?”

“Might as well.”

Adam continued singing and I picked up on the chorus: ahee ahee ah-ey, several times. We sang it loud, amplified by our fear of the waves.

It was just us in a chip of wood out there, doing something stupid for nothing.

After seven hours we made it to the other side. We watched over our shoulders, as the cliffs grew taller and clearer. Drawing in under the lee we could see details; small trees growing out of pockets of dirt in crevices here and there. We had a hell of a time getting our dories into Dark Harbor and had to pull them in against the tide with ropes from shore.

“You rowed across from Lubec?” the Canadian Customs man asked.

“Yeah.”

“Kind of dirty day for it wasn’t it?”

“Yeah.”

“What you do it for, fun?”

I stood there exhausted while the rest of the gang napped on the beach. “I wouldn’t say fun,” I told him. “Just something we had to do.”

Adam and I had a fight that night that spilled over into the next day. We caught a ride home with a lobsterman and Adam went off to Boston for his operation. We didn’t talk for six months, but now we’re friends again. Last I heard from him, he said he was still alive, knock on wood.

Paul Molyneaux lives in East Machias and is the author of A Child’s Walk in the Wilderness published in 2013 by Stackpole Books.Magazine Issue #

Display Title

The Crossing

Secondary Title Text

It's a long row from Lubec to Grand Manan