The eagle figurehead that Bellamy carved for USS

Lancaster is considered his masterpiece. The piece, as seen today in the entrance hall of The Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, Virginia, marked a turning point in the visualization of the American eagle from ponderous realism to a simpler yet more expressive form of sculpture. Collection of The Mariner’s Museum.

By James A. Craig

Gilded wings spread wide in regal majesty, a razor-sharp beak emitting a fierce scream, the flag and shield of the American nation held safely in the steely grip of a raptor’s talons. Such are the trademarks of one of the most recognized and sought-after pieces of American art: the defiant and proud Bellamy Eagle.

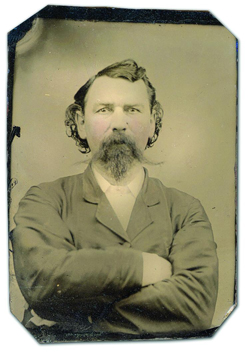

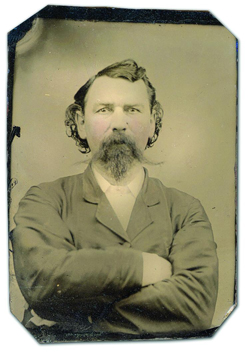

John Haley Bellamy was at the peak

of his career as a ship carver when

this ambrotype was taken, circa 1876.

Collection of the William A. Farnsworth

Library and Art Museum.

Considered to be one of the pinnacles of American woodcarving, the Bellamy Eagle ranks up there with such hallowed icons as the Statue of Liberty, the Great Seal of the United States, and Old Glory itself in representing the United States. Yet what of its creator? Who was the man responsible for giving flight to this most celebrated piece of Americana?

The son of a housewright, boatbuilder, and inspector of timber, John Haley Bellamy was born in the seaside community of Kittery, Maine, on April 16, 1836. Through the example of his ambitious father, the Honorable Charles Gerrish Bellamy, he gained his first exposure to the woodcarver’s vocation. When the time arrived to leave home, the young Bellamy apprenticed to an established woodcarver. Despite old claims that Boston woodcarver Laban S. Beecher was his master, new research shows that Bellamy was in fact formally trained by Samuel Dockum. This versatile craftsman from neighboring Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was a house and ship carver who made everything from bureaus, Grecian couches, coffins, and rocking chairs to the finish work on many Piscataqua River-built clipper ships. Dockum’s prosperous workshop offered Bellamy a superb opportunity to learn the woodcarver’s trade from an accomplished and respected artisan. Bellamy’s apprenticeship likely lasted six years after 1851, when he began working for Dockum at the age of 15, to 1857.

These bigger eagle carvings hung in civic offices and embodied the sprit of the country at a time when America was muscling its way onto the world stage. “God Is Our Refuge and Strength” eagle plaque: painted and gilded pine, ca. 1872–1900, 17" x 48", private collection. Photo by Corey O’Neil/CMO Photography.

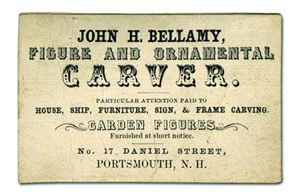

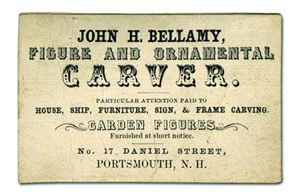

Two years later, Bellamy established a studio at 17 Daniel Street in Portsmouth, in rooms he likely rented from Dockum. His business card advertised himself as a master woodcarver capable of the full array of jobs. An 1859 newspaper article notes that he was primarily engaged as a decorative ship carver, furnishing figureheads for the shipbuilders of Portsmouth.

By October of 1859 Bellamy relocated to the shipyards of East Boston and Medford, Massachusetts, the epicenter of mid-19th-century shipbuilding in New England. With the coming of the American Civil War, he left his commercial clientele behind to work as a decorative ship carver for the United States Navy. Working first at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, then at the Charlestown, Massachusetts, Navy Yard, Bellamy began a lifelong association with the Navy that lasted as late as 1898.

Bellamy’s business card in 1859 noted the wide

variety of his woodworking skills. Collection

of the William A. Farnsworth Library and

Art Museum.

He made a wide array of carvings for use aboard many of America’s warships: from catheads and billetheads to sternboards and figureheads, no facet of a warship’s exterior that could accommodate decorative woodcarving was beyond his reach. His most celebrated creation was the USS

Lancaster eagle figurehead. Conceived and carved between December 1879 and August 1881, this majestic, graceful eagle is Bellamy’s masterpiece. It is as much a feat of engineering as a work of art, given the challenges of holding the 3,000 pound gilded pine carving with an 18-foot wingspan intact atop the bow of a warship that was subjected to the unforgiving oceanic environment for more than 20 years.

Bellamy returned home to the Piscataqua region by September of 1872, and commenced to work once again at the Portsmouth Navy Yard. Due to long bouts of unemployment between projects in the post-Civil War navy yards, and recognizing the economic opportunity of the region’s blossoming tourism industry, Bellamy turned his hands toward carving eagle sculptures for the commercial tourist market.

His first commissions were for large eagles in the round or long, wide forms for commercial and civic clients. Placed conspicuously in areas of high traffic, these eagles not only provided Bellamy income, but popularized another type of eagle carving he had first conceived when in Charlestown. Known today as

the “Bellamy eagle,” these two-foot wide painted plaques—with their unmistakable sense of swiftness, intensity, and strength—are celebrated pieces of Americana, enthusiastically sought by collectors of folk and fine art alike.

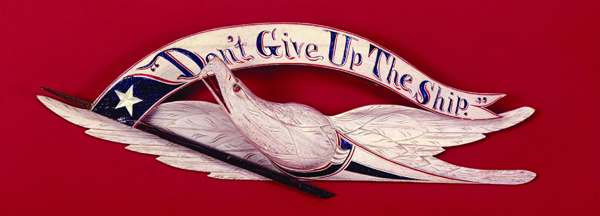

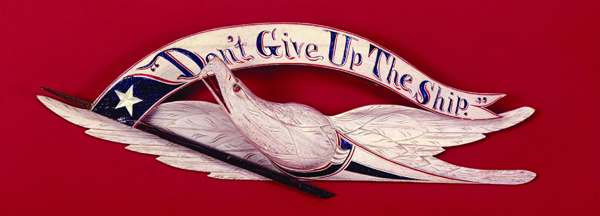

Other messages on Bellamy’s small eagles included “Merry Christmas,” “Remember the Maine,” and even the politically inspired “Long Live Dewey.” “Don’t Give Up The Ship” eagle: painted pine, ca. 1872–1900, 9" x 25". Courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. Photo by David Bohl.

Easily transportable, affordably priced (only $1 or $2 apiece at the time), and sporting any number of political, fraternal, religious, and holiday sentiments, the Bellamy eagle appealed to a wide and diverse clientele. Consisting of only four pieces held together with a minimum of hardware, they were easy to assemble. This was intentional, for Bellamy filled orders for as many as 500-700 at a time for local patrons like Portsmouth brewer Frank Jones, as well as customers further afield, like The Manhattan Storage & Warehouse Company of New York City.

He made a wide array of carvings for use aboard many of America’s warships: from catheads and billetheads to sternboards and figureheads, no facet of a warship’s exterior that could accommodate decorative woodcarving was beyond his reach.

Yet even while producing some of the more elaborate, formal eagle plaques for which he is recognized, Bellamy also toiled as a house carpenter, fashioning interior and exterior decorative carvings for Portsmouth and Kittery homes. And in true woodcarver fashion he also carved furniture and works of pure whimsy. Contrary to the prevailing stereotypical vision of the folk artist as a provincial backwoods whittler, Bellamy was a literate poet and urbane raconteur who enjoyed close personal friendships with many of the leading literati of his day, including artist Winslow Homer and authors William Dean Howells, Marion Crawford, George Savary Wasson, and Mark Twain.

The eldest of 10 children, Bellamy was the last of his siblings to die. His hands gnarled with arthritis, his mind deteriorating with age, by February 1, 1911, Bellamy was deemed legally incompetent and forced to reside with a cousin in Portsmouth until he passed away from a stroke on April 5, 1914.

A full century later John Haley Bellamy continues to inspire. Carvings that had cost $1 when first crafted today easily fetch as much as $160,000 at auction; larger and more exquisite pieces have sold for $660,000. His was an artistic vision that has defied changing temperaments and fashions. To gaze into the fierce eye of a Bellamy eagle is to look into the very soul of the American nation—a soul that, like Bellamy’s art, is still very much alive and active today.

James A. Craig (

www.jamesacraig.com) is an independent curator and author specializing in American marine art. He is the author of

American Eagle: The Bold Art & Brash Life of John Haley Bellamy (Portsmouth Marine Society Press, 2014).

Secondary Title Text

The bold art of John Haley Bellamy, America's greatest ship carver

The eagle figurehead that Bellamy carved for USS Lancaster is considered his masterpiece. The piece, as seen today in the entrance hall of The Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, Virginia, marked a turning point in the visualization of the American eagle from ponderous realism to a simpler yet more expressive form of sculpture. Collection of The Mariner’s Museum.

The eagle figurehead that Bellamy carved for USS Lancaster is considered his masterpiece. The piece, as seen today in the entrance hall of The Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, Virginia, marked a turning point in the visualization of the American eagle from ponderous realism to a simpler yet more expressive form of sculpture. Collection of The Mariner’s Museum.

John Haley Bellamy was at the peak

of his career as a ship carver when

this ambrotype was taken, circa 1876.

Collection of the William A. Farnsworth

Library and Art Museum.

John Haley Bellamy was at the peak

of his career as a ship carver when

this ambrotype was taken, circa 1876.

Collection of the William A. Farnsworth

Library and Art Museum.

These bigger eagle carvings hung in civic offices and embodied the sprit of the country at a time when America was muscling its way onto the world stage. “God Is Our Refuge and Strength” eagle plaque: painted and gilded pine, ca. 1872–1900, 17" x 48", private collection. Photo by Corey O’Neil/CMO Photography.

These bigger eagle carvings hung in civic offices and embodied the sprit of the country at a time when America was muscling its way onto the world stage. “God Is Our Refuge and Strength” eagle plaque: painted and gilded pine, ca. 1872–1900, 17" x 48", private collection. Photo by Corey O’Neil/CMO Photography.  Bellamy’s business card in 1859 noted the wide

variety of his woodworking skills. Collection

of the William A. Farnsworth Library and

Art Museum.

Bellamy’s business card in 1859 noted the wide

variety of his woodworking skills. Collection

of the William A. Farnsworth Library and

Art Museum.

Other messages on Bellamy’s small eagles included “Merry Christmas,” “Remember the Maine,” and even the politically inspired “Long Live Dewey.” “Don’t Give Up The Ship” eagle: painted pine, ca. 1872–1900, 9" x 25". Courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. Photo by David Bohl.

Other messages on Bellamy’s small eagles included “Merry Christmas,” “Remember the Maine,” and even the politically inspired “Long Live Dewey.” “Don’t Give Up The Ship” eagle: painted pine, ca. 1872–1900, 9" x 25". Courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques; Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. Photo by David Bohl.