Skin-on-frame construction has been used in boatbuilding since the Neolithic period. Learning the knots that hold the frame together is a way to touch the distant past.

Story & Photos by Paul Molyneaux

Down on the shore, we watch a big ocean swell lift a raft of kelp and sweep it toward the rocks. The fronds dance in the breaking wave, and wash back into the next swell, over and over.

“It’s like breathing,” says my 11-year-old son, who answers to the nickname, Venado (Spanish for “deer”).

“Yeah. If you close your eyes it even sounds like breathing.”

We sit there talking about his home schooling. He hates learning math from books.

“What about building a kayak?” I ask.

He looks up. “Yeah!”

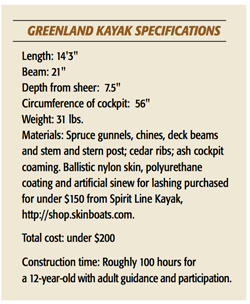

Asher “Venado” Molyneaux paddling his

new Greenland kayak in July 2014, on

the estuary of the East Machias River.

The design for the traditional kayak came

from

Building the Greenland Kayak:

A Manual for Its Construction and Use,

by Christopher Cunningham.

Going out in boats has always felt like a way of talking to the sea, and the conversation cannot get any more intimate than sitting on the ocean surface in a kayak, paddling over every wave or sometimes under them. Knowing what we want to say, we begin to figure out how we will say it.

Back home we dig out Edwin Tappan Adney’s classic,

Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America, and flip to the section on kayaks. We examine Aleutian baidarkas with their high deck ridges, and Greenland kayaks built long and slender for rolling. Via the Internet we locate descriptions of construction methods: stitch-and-glue and cedar strip require tools we do not have. We are more like the circumpolar peoples who used stone and bone tools to build the first kayaks from driftwood and sealskin, so we settle on building a skin-on-frame Greenland-type kayak. In the interest of pushing the math we lay down lines for one at 1/8 size, but we never build it. Instead we discover Christopher Cunningham’s book,

Building the Greenland Kayak, and it becomes our bible. We adopt the more indigenous building methods he describes, albeit with some contemporary short-cuts.

Our neighborhood sawyer donates planks of clear spruce for the gunnels and chines. In early December, we carry our chainsaw into the woods looking for cedar and ash. “Keep your eyes open and trust we’ll find what we need,” I tell my son.

An hour later, amidst the smell of cedar chips and chainsaw fumes, I point to one of the three-foot-long cedar logs I have cut for rib stock. “Can you carry one of those?”

“I think so.”

He takes one and when we get them home we split out the ribs with a froe. We take turns. Everything goes slowly. We’re in school, with Christopher Cunningham as our teacher. I’m reading Cunningham’s book, thinking through the myriad of intimidating processes and wondering if we can actually pull it off, when Venado makes some off-hand comment about paddling the finished product. He can already see it done, and I don’t want to let him down.

Because we are tight on workspace we lay the gunnels on the floor of our den—they fit if we open the door to my daughter’s bedroom—and as we add the deck beams and frames the kayak takes shape.

“Looks like you’re canoe building,” a visitor says.

“Kayak,” we say in unison.

Steel tools quicken the work, but we find ourselves relearning Neolithic lessons as we peg and tie the pieces together using the same knots used by the Inuit who displaced the Vikings in Greenland a thousand years ago. Inevitably Venado asks about the different kayak designs, and we revisit the notion of a dialogue with the sea. The kayak, we learn, originated at least 3,000 years ago with the Okvik culture in Siberia and western Alaska. The rough conditions faced by these proto-Inuit whalers in their home waters, combined with the limited materials and tools they had to work with, made for a conversation dominated by nature. As a result, the kayak is a humble vessel that surrenders to the sea. Inuit hunters often rolled their boats over to avoid the backbreaking impact of big waves. “Roll or die,” reads a bumper sticker popular among modern Greenland kayakers.

At the end of each workday we lift the kayak frame up on top of two book- cases in opposite corners of the den. When my wife comes in, she looks up before sitting down to finish her day’s work. “How long’s this going to be here?” she asks. “And how will you get it out?”

“Out the window.”

Once the weather warms Venado moves the boat outside. Alone, he completes the masik—the arched deck beam that raises the foredeck of the Greenland kayak—and oils the finished frame. Bending the cockpit coaming requires four hands. The wood does not fit into the steam box, so we bend one end to “teach” it, and then we let it straighten out so we can steam the other end. “Ready?” I ask, when we can smell it cooking. Venado nods.

The wood comes out piping hot; with gloved hands we wrap it around the form, bending the full circle.

“Clamp there,” I tell him, as I strain to hold the wood in place and bring the end home, but it’s too late. The wood has cooled. On the second try Venado gets the clamps on in time. Two days later we stretch the ballistic nylon fabric over the frame and discover it is six inches too short, my miscalculation.

“Oh no, Papa, what are we gonna do?”

“We’ll be okay. They say it needs to stretch at least four inches.”

We cut an inch off the stem and stern and fair the angles a bit. Then, after sewing pockets on each end, we hook one end of the nylon over the sternpost and lash the bow pocket to an old peavey handle that we use to lever the skin on.

“Hurry sew that up, get the strain off the one end,” I tell my son. The next day he starts sewing the seams, and by the end of the second day it’s ready for a coating of urethane. But he has to leave for camp before it dries.

“Nobody’s touching it,” we assure him.

He returns in late July and a friend helps him carry the slender craft down to the East Machias River. Using the paddle he carved from a piece of poplar, Venado paddles far down the estuary.

Besides an indigenous approach to applied math and handling sharp tools, Venado has learned how to set a realistic goal and reach it. Before he heads for open water, though, he will need to learn the language of kayaks. As generations of paddlers know, confidence and humility are the two ends of the same paddle; it’s an important life lesson best summed up in the Greenland kayaker’s motto: “Roll or Die.”

Paul Molyneaux lives in East Machias and is the author of

Child’s Walk In The Wilderness published in 2013 by Stackpole Books.

Secondary Title Text

The deeper lessons of kayak building

Skin-on-frame construction has been used in boatbuilding since the Neolithic period. Learning the knots that hold the frame together is a way to touch the distant past.

Skin-on-frame construction has been used in boatbuilding since the Neolithic period. Learning the knots that hold the frame together is a way to touch the distant past. Asher “Venado” Molyneaux paddling his

new Greenland kayak in July 2014, on

the estuary of the East Machias River.

The design for the traditional kayak came

from Building the Greenland Kayak:

A Manual for Its Construction and Use,

by Christopher Cunningham.

Asher “Venado” Molyneaux paddling his

new Greenland kayak in July 2014, on

the estuary of the East Machias River.

The design for the traditional kayak came

from Building the Greenland Kayak:

A Manual for Its Construction and Use,

by Christopher Cunningham.