Sedum and Geranium sanguineum 'Max Frei' are shown here in full flower. Sedums thrive in less-than-ideal conditions, which makes them perfect for rock gardens. Photo by Lynn Karlin

Sedum and Geranium sanguineum 'Max Frei' are shown here in full flower. Sedums thrive in less-than-ideal conditions, which makes them perfect for rock gardens. Photo by Lynn Karlin

Each spring as we turn the soil for the vegetable garden we harvest buckets full of fist-sized (and bigger) rocks. Some years it seems as if the thing we grow best is rocks. It reminds me of that kitschy tourist item, the little plastic bag of pebbles labeled “seeds for rock walls.”

The rocks in our gardens come from deep down below the surface in vast fields of subterranean rubble left by retreating glaciers at the end of one of the ice ages. In the winter, successive freeze and thaw events heave the submerged rocks upward until they pop out of the ground like the tulips in the spring. Surprise! While mostly the smaller ones—the stones—work up through the loam, there are some pretty big boulders slowly being pushed up as well.

We have one “growing” in our backyard. Every year we discover that the rocky lump in the lawn is bigger than it was the year before. It probably is as big as a Volkswagen Beetle, though the part we see is only the size of a hubcap. When I try to sink a digging fork three or four feet from its center, I get a substantial “clunk.”

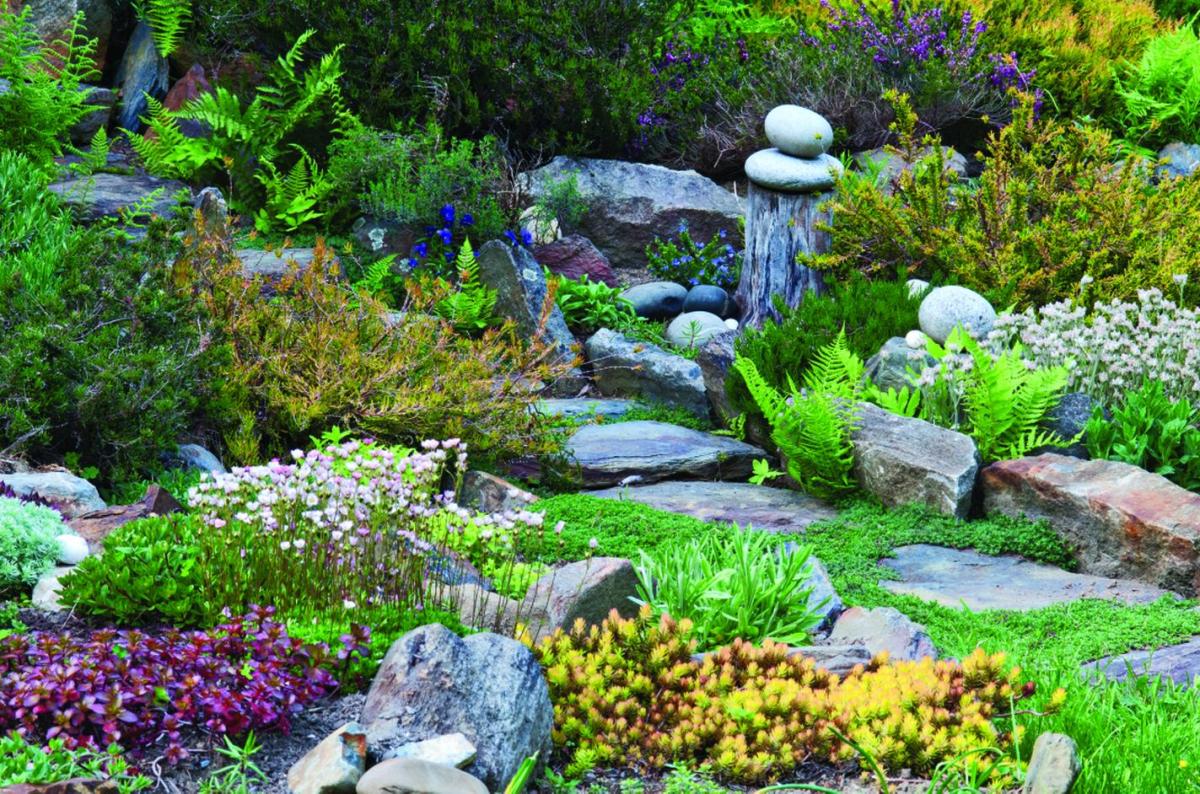

Rock gardeners like to use slow-growing plants that creep, cling, crawl, and dangle. In early spring, a rocky path winds through low-growing sedum and ameria in Kristie Scott’s Lincolnville garden. Heaths, heathers, and lavender fill in as the season progresses. Photo by Lynn Karlin

Rock gardeners like to use slow-growing plants that creep, cling, crawl, and dangle. In early spring, a rocky path winds through low-growing sedum and ameria in Kristie Scott’s Lincolnville garden. Heaths, heathers, and lavender fill in as the season progresses. Photo by Lynn Karlin

It’s no accident that Maine has hectometer after hectometer of old rock walls. Farmers and gardeners over the ages have been toting rocks to the edges of farms and fields in buckets and barrows simply to get them out of the way. Still, the resulting walls served quite well, thank you, to mark boundaries and keep pastured animals where they belonged. Then there are the ledges, those great hulking sheets of granite that lurk just below the surface for acres on end. “Bony soil,” they call it.

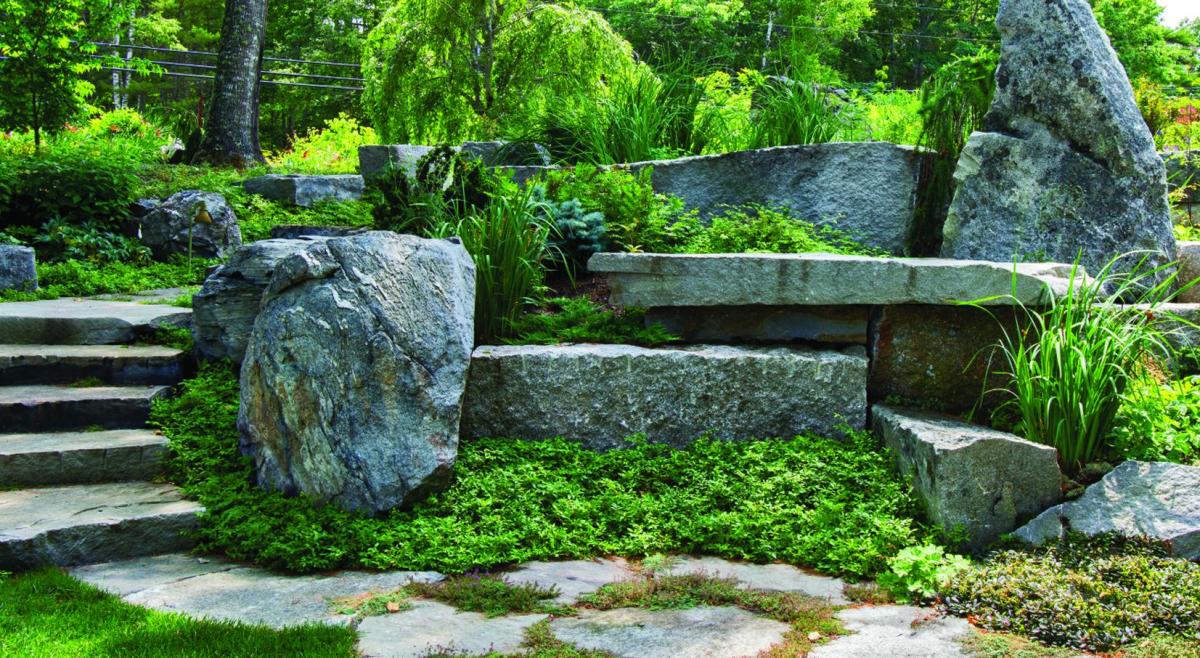

The Goff gardens on Taunton Bay in Hancock were designed by Bruce John Riddell of Land Art. He used massive amounts of Maine stone to provide four-season interest and complement many native plants, including swaths of hair cap moss, hay-scented fern, bunchberry, and wintergreen. Photo by Lynn Karlin

The Goff gardens on Taunton Bay in Hancock were designed by Bruce John Riddell of Land Art. He used massive amounts of Maine stone to provide four-season interest and complement many native plants, including swaths of hair cap moss, hay-scented fern, bunchberry, and wintergreen. Photo by Lynn Karlin

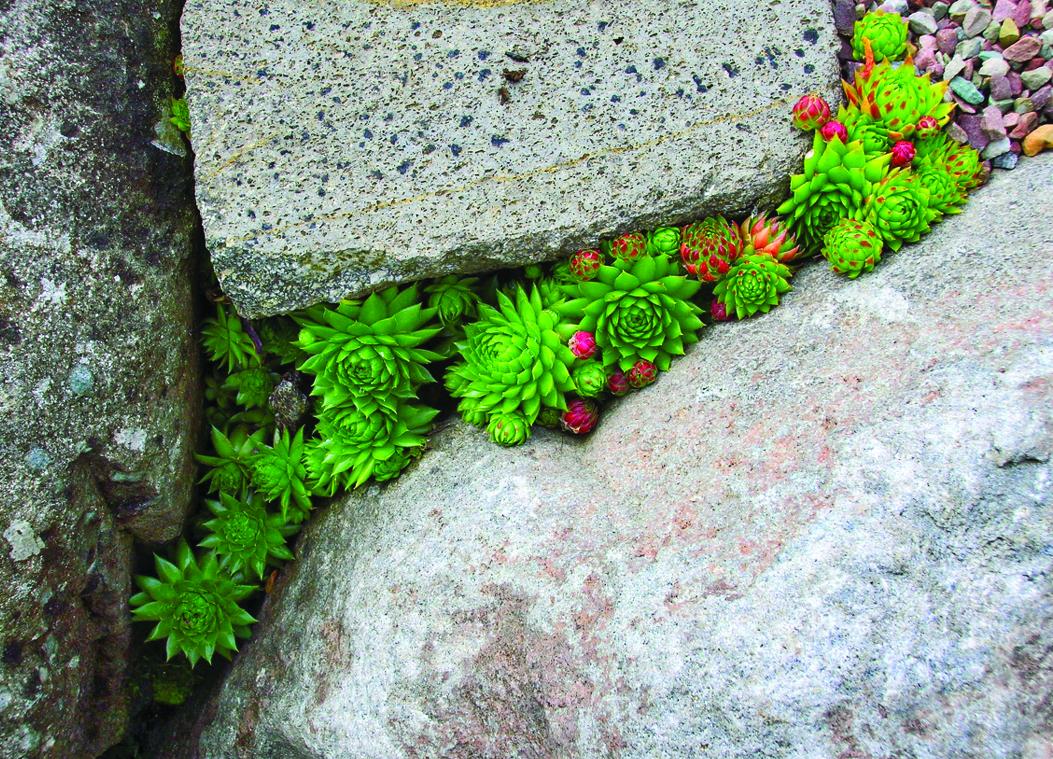

Enter rock gardens—the lemonade that gardeners make when they have too many rocks. Maine has some of the most wonderful rock gardens to be found anywhere, and some of the most creative gardeners. For some, a rock garden is the ultimate gilding of the lily. For others it is a colorful, and often creative, response to the conditions at hand. A line of hens and chicks, rock-hugging sedums, nestles into the crevice of a rock garden. Photo by Lynette Walther

A line of hens and chicks, rock-hugging sedums, nestles into the crevice of a rock garden. Photo by Lynette Walther

Imagine planting a garden on a parking lot. That’s basically what many rock gardeners do: utilize every crack, fissure, crevice, and pothole to their advantage. While not the easiest to cultivate, once established, rock gardens have one big advantage over their more soil-bound counterparts—not many weeds can take hold on barren rock. Upkeep consists mainly of watering and trimming.

As early as the 1800s the concept of rock gardening captivated European gardeners, though the practice dates to early Chinese and Japanese gardens, which actually featured rocks more than plants. Garden designer and writer Reginald Farrer’s groundbreaking book The English Rock Garden, published in 1919, introduced the concept of cultivated “hillsides” of Alpine plants to the rest of the world. That was a time of plant frenzy as explorers scoured the globe for exciting new botanical varieties.

Today’s gardeners are experiencing a renaissance of that frenzy as plant developers create vibrant new choices through tissue culture breeding techniques. In addition, heirloom varieties are being rediscovered and made available. Rock gardeners covet slow-growing plants that spread, creep, cling, crawl, and dangle. Drought tolerance is a plus. The fairly recent introductions and increasing availability of the traditional first-choice of rock garden plants—the Alpine plants—plus colorful new, cold-hardy sedums, dwarf conifers, lavenders, dwarf irises, and a host of other diminutive plants specifically bred for rock gardens have only increased interest, especially here in this most rock-bound of states. Even moss is getting its due—Boothbay’s Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens gives workshops in moss gardening on rocks.

No longer merely the byproduct of a day’s work, Maine’s rocks are getting all gussied up, commanding center stage.

Contributing Editor Lynette L. Walther is the recipient of the Garden Writers Association’s Silver Award of Achievement. She gardens in Camden, Maine. Her blog can be found at: gardeningonthego.wordpress.com.

For more information:

Visit www.maineboats.com and follow the lead of two Maine gardeners, Vickie Cunningham in South Bristol, and Douglas Cole in Rockport, who have worked magic with rocks and stones and a ledge or two.

The nuts and bolts of rock gardening

A rock garden is designed to replicate an Alpine environmnet, and the plants represent slow-growing varieties. Here are a few principles:

Location—Choose a sun-filled slope or ledge, preferably with a southern or southeastern exposure, as most rock garden plants require full sun (at least six hours).

Rocks—Ledge is ideal, however, large rocks or boulders of similar type and varying sizes can be worked to create a ledge-like planting surface. Bury rocks of varying sizes at irregular intervals so that about two thirds of the rocks are exposed and create pockets for planting.

Soil—Rock garden plants require excellent drainage, and benefit from a three-part planting medium: a mixture of soil, compost, and coarse sand or gravel.

Plants—Traditionally slow-growing Alpine plants fill rock gardens, although today there are numerous new cultivars of small or dwarf plants for dry and rocky soils such as sedum, Cheilanthes, oregano, phlox, scutellaria, sempervivum, and

hesperaloe. For an extensive list of rock garden plants, visit the website of the North American Rock Garden Society: www.nargs.org.

Maintenance—Because rock gardens support slow-growing species, fertilization is rarely necessary as it promotes rapid growth that cannot be sustained by the rocky environment. The rocky surfaces also often discourage weed growth. However, the well-drained growing medium of a rock garden can dry out quickly, and regular irrigation is usually required. A winter mulch can help prevent freeze damage.