Eleanor and FDR revealed their engagement after a visit to the Roosevelt family’s summer home in 1904. This photo of them was taken during that visit. Photos courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.In one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s last syndicated newspaper columns, she wrote about the summer home on Campobello Island that she and Franklin loved. She had come to the island, located on the border between Maine and Canada, for the dedication of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Bridge. Although she was too ill to attend the ceremony, in her August 10, 1962 My Day column she looked back on the island’s history, its people, and what they meant to her family: “Those of us who remember the past will have a nostalgic feeling for the days when you could spend a month or six weeks, virtually cut off from the world and its troubles, enjoying to the full the ‘beloved island,’” as FDR’s family always called it.

Eleanor and FDR revealed their engagement after a visit to the Roosevelt family’s summer home in 1904. This photo of them was taken during that visit. Photos courtesy of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.In one of Eleanor Roosevelt’s last syndicated newspaper columns, she wrote about the summer home on Campobello Island that she and Franklin loved. She had come to the island, located on the border between Maine and Canada, for the dedication of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Bridge. Although she was too ill to attend the ceremony, in her August 10, 1962 My Day column she looked back on the island’s history, its people, and what they meant to her family: “Those of us who remember the past will have a nostalgic feeling for the days when you could spend a month or six weeks, virtually cut off from the world and its troubles, enjoying to the full the ‘beloved island,’” as FDR’s family always called it.

FDR teases his cousin, Jean Delano about her hair, during a sail on his father’s 60-foot schooner, Half Moon II, in 1910.

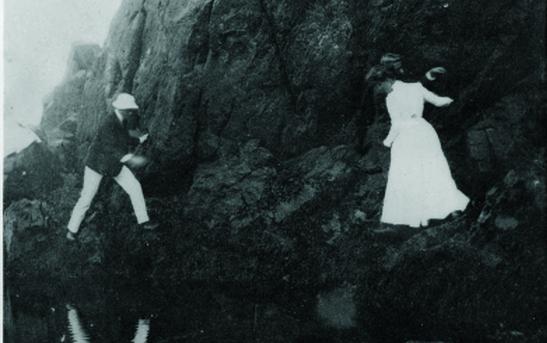

FDR teases his cousin, Jean Delano about her hair, during a sail on his father’s 60-foot schooner, Half Moon II, in 1910.The president first came to the island as a young child. In 1883, his parents, James and Sara Roosevelt, of Hyde Park, New York, brought their one-year-old son to vacation at the new Tyn-y-Coed (Welsh for ‘in the woods’) Hotel because James had heard about exceptional sailing in the region. At the height of the Victorian era, the Campobello Co. was developing a summer resort for wealthy, socially prominent families. Its “rustic” hotels and wicker-furnished cottages were marketed as a tonic for those wishing to escape loathsome city heat. Ocean breezes would provide a restful night’s sleep and relief from hay fever, promoters said. Serene balsam fir forests and ever-changing downeast views promised tranquility in contrast to industrialized cities.  FDR and friends climb rocks along the shore in Campobello in 1902. He was 20 and in college at the time.

FDR and friends climb rocks along the shore in Campobello in 1902. He was 20 and in college at the time.

As “rusticators,” the Roosevelts were far from disappointed. Two years later, James and Sara purchased land and a 15-room cottage overlooking Friar Bay.

Although never large, the summer colony thrived until World War I. In its heyday, the resort was designed for large families who made arduous journeys by train and steamship from Boston, New York, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Montreal, and London, bringing abundant staff, guests, and vast amounts of luggage. Days revolved around tennis and lawn games, swimming, horseback riding, birding, hiking, shooting, sailing, and picnics. Reading and conversation filled the cool evenings and days of less favorable weather.

FDR and a group of family and friends picnic on the beach in 1906.

FDR and a group of family and friends picnic on the beach in 1906.“Campobello to FDR, as a boy and as a young man, was an idyllic place full of adventure, nature, and challenges, with the freedom to truly be on his own,” wrote his grandson, Christopher duPont Roosevelt, one of two family members currently on the park’s board. “Early in his life, the children of the island, not just the summer colony children, were his friends and playmates… Later they were the ‘ordinary’ folks who knew his respect for them, who treated him as a trusted friend and neighbor, with whom FDR felt totally at ease because of a mutual sense of appreciation that passed between them.”

FDR’s love of boats began at a young age. Here he is at the age of 8, playing with friends on a scow on their lawn in Campobello. His first boat of his own was the 21-foot knockabout New Moon, which he got when he was 16. Unlike in Hyde Park, here he could do as he wished. He swam in the chilly Bay of Fundy, canoed in Cobscook and Passamaquoddy bays, explored woods and bogs, led hikes and rode horses. The summer crowd employed islanders as captains and crew for their yachts, the most prominent of which was James Roosevelt’s 51-foot Half Moon. Captains Franklin Calder and Eddie Lank taught young Franklin to sail. He learned quickly and well. When Roosevelt was 10, Lank reportedly told him, “You’ll do now. You’re a full-fledged seaman, sardine sized.”

FDR’s love of boats began at a young age. Here he is at the age of 8, playing with friends on a scow on their lawn in Campobello. His first boat of his own was the 21-foot knockabout New Moon, which he got when he was 16. Unlike in Hyde Park, here he could do as he wished. He swam in the chilly Bay of Fundy, canoed in Cobscook and Passamaquoddy bays, explored woods and bogs, led hikes and rode horses. The summer crowd employed islanders as captains and crew for their yachts, the most prominent of which was James Roosevelt’s 51-foot Half Moon. Captains Franklin Calder and Eddie Lank taught young Franklin to sail. He learned quickly and well. When Roosevelt was 10, Lank reportedly told him, “You’ll do now. You’re a full-fledged seaman, sardine sized.”

He became a skilled and daring mariner, which prepared him as an adult to handle ships, command crews, and pilot naval destroyers through the treacherous Lubec Narrows. He also loved to canoe. Tomah Joseph of Maine’s Passamaquoddy Tribe taught him to maneuver along the coast and to patiently observe wildlife from a canoe. As a young man, among his favorite days were those spent circling the island in a birch bark canoe made for him by the Passamaquoddy Indians in 1907, wrote Eleanor in her column.

FDR and Eleanor with their baby daughter Anna and friends on a sailboat in Campobello in 1907. It was after a day of sailing in 1921 on his yacht Vireo that FDR became sick with polio. Historians believe he was infected while visiting a Boy Scout encampment in New York a few weeks earlier.Eleanor was Franklin’s fifth cousin, once removed. Her parents, Anna Hall and Theodore Roosevelt’s younger brother, Elliott, both died before she was 10, leaving Eleanor to be raised by her maternal grandmother. After several years at boarding school in England, at 18 she returned to New York. One day, she happened to be on the same train as Franklin, whom she had met briefly years earlier. Their chance encounter led to romance and a secret engagement that was revealed at the end of a month-long visit with Franklin’s mother, Sara, on Campobello Island. In March 1905 in New York, President Theodore Roosevelt gave his niece away.

FDR and Eleanor with their baby daughter Anna and friends on a sailboat in Campobello in 1907. It was after a day of sailing in 1921 on his yacht Vireo that FDR became sick with polio. Historians believe he was infected while visiting a Boy Scout encampment in New York a few weeks earlier.Eleanor was Franklin’s fifth cousin, once removed. Her parents, Anna Hall and Theodore Roosevelt’s younger brother, Elliott, both died before she was 10, leaving Eleanor to be raised by her maternal grandmother. After several years at boarding school in England, at 18 she returned to New York. One day, she happened to be on the same train as Franklin, whom she had met briefly years earlier. Their chance encounter led to romance and a secret engagement that was revealed at the end of a month-long visit with Franklin’s mother, Sara, on Campobello Island. In March 1905 in New York, President Theodore Roosevelt gave his niece away.

The newlyweds spent the next two summers at the Roosevelt family’s island cottage. Grace Kuhn, who lived next door, grew so fond of them that in her will she stated Sara could buy her cottage for $5,000, but only if Sara gave it to Franklin and Eleanor when she died. The cottage next door became the first home of their own, dearly loved by Franklin but transformative for Eleanor. It was her first home not dominated by her grandmother or mother-in-law. Here she honed her organizational skills, coordinating family life, meals, tutors, servants, guests, and transportation.

“My grandmother felt most comfortable here because she was finally master of her own domain,” wrote Christopher, whose father, Franklin, Jr., was born in the upstairs bedroom, joining siblings Anna, James, Elliott, and John. (A sixth child, also named Franklin, Jr., died in infancy.) Visitors today see the house as if the family had just stepped out. Eleanor’s knitting waits beside her chair. A giant megaphone rests where she used it to call the children in for meals and lessons. Ship models Franklin built with his sons are displayed.

FDR’s birchbark canoe was built for him by Tomah Joseph, a member of the Passamaquoddy Indian Tribe, who also taught him how to canoe. This photo was taken in 1907 when FDR was 25.

FDR’s birchbark canoe was built for him by Tomah Joseph, a member of the Passamaquoddy Indian Tribe, who also taught him how to canoe. This photo was taken in 1907 when FDR was 25.

Eleanor helped with fundraising for community plays and even performed in one. She played a tree, so she wouldn’t be in the limelight. She also organized frequent picnics and daily afternoon tea.

Today, Theresa Mitchell, a ninth-generation Campobello resident, coordinates popular “Tea with Eleanor” programs at the Roosevelts’ former home. Over cookies and tea, local guides talk about Eleanor’s life. “Anna McGowan, who cooked for the Roosevelts, said there was no way to plan an afternoon tea or meal because Eleanor would invite people as she passed them while riding her bike or walking,” Mitchell recounted. “Eleanor Fletcher, who attends our teas, tells about being at a dance at the hall and complimenting Eleanor on what a beautiful dress she was wearing. Eleanor simply said ‘Sears and Roebuck,’ which was what local women wore. It would have meant a lot to them.”

The family’s life was upended abruptly in August 1921. Franklin, 39, had been defeated one year earlier in his first run for national office, as vice president. While planning his political future, he spent a day sailing with the family, during which they extinguished a small forest fire. Then he went for a long run and a swim. He returned chilled and exhausted, and went to bed. In the morning, one of his legs dragged. Leaving the bedroom, he collapsed in the upstairs hall. Soon he lost all movement below the waist. Two weeks of painful, regular massages failed to help. Finally he was diagnosed with polio.

In early September, as his children watched in horror, a team of island neighbors carefully carried FDR down the long staircase, across the veranda, down the steep hill to a waiting boat for the trip to New York. It would be 12 years before FDR returned to Campobello, this time as president.

In 1933, after his first 100 days in the White House, he sailed the yacht Amberjack II with his three sons through Lubec Narrows to Welshpool Harbor, where he was welcomed by the Campobello fishing fleet and a crowd. A naval communications ship anchored in the bay. According to Mitchell, “Eleanor decided to plan a picnic. She invited the staff and officers of the USS Indianapolis, dignitaries from Maine and New Brunswick, Franklin’s friends, and the local residents. Eleanor could [just] scramble eggs and toast bread [so] she called upon the local ladies to help, and without a hitch, she had the picnic.”

The president returned only twice more, in 1936 to sail, and briefly in 1941 aboard the USS Tuscaloosa. He died in 1945.

Many of the programs he designed while in office reflected lessons this son of wealth and privilege learned from people on Campobello, people whose lives differed greatly from his own. These included Social Security; the Civil Works Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps, which created jobs; and the Federal Housing Administration to regulate mortgages.

As first lady, Eleanor continued to visit with friends and use the cottage as a retreat. She wrote one of her four autobiographies and numerous My Day columns there.

“Maine is so remote that many of the affairs of vital interest to other people in the country may mean little here. But the Battle of the Atlantic is very close to these people. They see ships being built. They have known men of the Navy and they understand the life and risks of the sea which are simply augmented in times of war,” she wrote on July 31, 1941, four months before the United States entered World War II.

The column continued, “They must at times develop ingenuity, resourcefulness and determination to find some way of accomplishing at least a mere existence for themselves and their families. This means a constant battle with fate. It must make strong men and women.”

Contributing Editor Janet Mendelsohn is the author of Maine’s Museums: Art, Oddities and Artifacts (Countryman Press). She can be reached at www.janetmendelsohn.com.

If you go, bring your passport.

Courtesy Roosevelt Campobello International ParkCampobello is in the Atlantic Time Zone, one hour ahead of Maine. The Edmund S. Muskie Visitor Centre is open Saturday before Memorial Day to Oct. 31. The grounds and park are open year-round. Roosevelt Cottage tours take place 9-5 EDT (through Columbus Day), “Tea with Eleanor” programs run twice daily. For more information on Roosevelt Campobello International Park:

Courtesy Roosevelt Campobello International ParkCampobello is in the Atlantic Time Zone, one hour ahead of Maine. The Edmund S. Muskie Visitor Centre is open Saturday before Memorial Day to Oct. 31. The grounds and park are open year-round. Roosevelt Cottage tours take place 9-5 EDT (through Columbus Day), “Tea with Eleanor” programs run twice daily. For more information on Roosevelt Campobello International Park:

www.fdr.net or call 877-851-6663. For more on Campobello see Lee Wilbur’s travelogue at www.maineboats.com.