Dyon

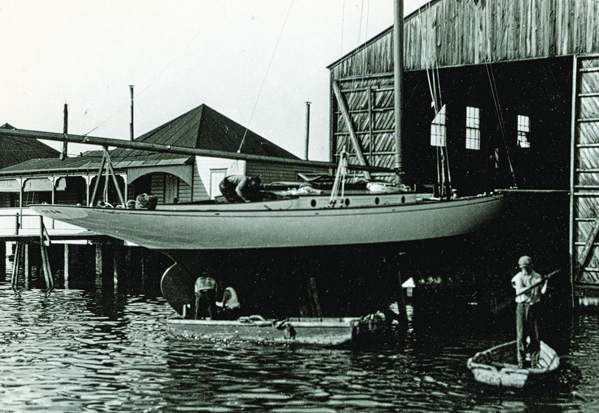

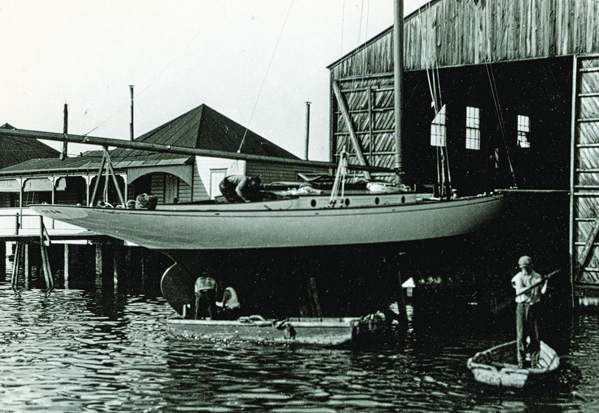

Dyon was designed by Bill Luders, with help from her owner P.L. Smith. This photo shows the newly finished yacht on her launching day in July 1924 at the Luders yard in Stamford, Connecticut.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

By Philip L. Smith

At some point in the summer, each of us goes to our boathouse (we call it the “shipyard”), pulls back the sliding door, and for a brief moment just stares.

The first time our father took us to see her out of the water, she lay in her cradle in one of Wayfarer’s red sheds at the head of Camden Harbor, where she spent the winter in the 1950s and 1960s. We were young; mostly what I remember is looking up at a green bottom that met a white hull that seemed to go up and on forever. Years before, writer Maynard Bray also saw her with his father who said, “That my boy, is a yacht.” In this age of resource-consuming mega-powerboat, she is no longer a yacht by any stretch of the definition. Rather, she represents a different time, and the notion of a simple marriage between beauty and function.

P.L. Smith, seen here at

the helm with his good friend Harold Foote,

sailed

Dyon up and down

the Maine coast.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

slid down the ways at Luders Marine Construction Co. of Stamford, Connecticut, in July 1924. As best we know, naval architect Bill Luders let my grandfather P.L. Smith help with the design. P.L. reportedly drove

Dyon hard, sometimes recklessly, throughout the late 1920s and 1930s, often with a crowd on board, and never with our grandmother. Other times, with a hardened crew of only two, he would prowl the Maine coast and its islands from Tenants Harbor up to the Canadian border.

When World War II came,

Dyon was laid up at Snow Shipyard in Rockland until our father bought her from the estate after P.L. died in 1943. By then

Dyon had been out of the water for seven years and the seams had opened up to the point that water being pumped into the bilge spilled out as through a colander. It took days of pumping after she slid down the ways before

Dyon could once again assume her role in the family.

Harts Neck in Tenants Harbor was, and still is, our family retreat—150 acres that P.L. acquired during the Depression. It is dotted with summer houses, each with its own name, all presided over by Munasca, P.L.’s stately “cottage” where the family would gather for at least three months to “rusticate.” P.L. Smith had four children: Horace (my father), Philip, Helen, and Betty; nine of his twelve grandchildren are still alive. We were born Flip (Philip L. II), Flop (Steve), and Fini (Dorsey) in 1945, 1946, and 1947. Mother never recovered. We’re still rusticating in Tenants Harbor as an extended family of approximately 100 cousins, including five living Philips.

The bronze hawk on

Dyon’s bow.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

A 1925 Rudder article about

Dyon called her “one of the most attractive yachts of her type (sloop) we have seen in plan. In form she has a slack bilge….” Well, maybe the bilge is slack, but there is nothing slack about the lines. The article continues, “but (she) seems to carry her sail well in heavy weather and at the same time be quite fast in light airs.” Clearly, whoever wrote that had never sailed her. She wallows in wind under 10 to 15 knots—unless, of course, that was the definition of “light airs” in those days.

“One feature of her layout is the big cockpit,” the Rudder article noted. True. It is

Dyon’s signature feature.

Dyon’s cockpit perfectly devotes itself to family and friends. She is for all intents and purposes a daysailer. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, we would invite as many as 20 people at a time for sails. Adults sat in the cockpit, while the rest of us

We treasured those nights in the harbor when she lay on her mooring off the neck and our parents would let us have friends spend the night on board.

sprawled on the varnished cabintop and deck, sunning ourselves. Talk was small if one talked at all. At some point, someone might go to the bow to lie down next to the small bronze hawk head (Dyon is the Indian word for hawk) mounted there, or stand up and brace against the forestay to feel the wind and watch the bow of this 20-ton sailboat quietly and powerfully slice through the water. Mind you this was decades before Hollywood had Leonardo DiCaprio do the same on the bow of the Titanic.

The Smith family has owned

Dyon

for 90 years, ever since she was built. The wooden yacht

is kept in a large boathouse in Tenants Harbor, Maine,

where assorted family members help to paint and launch

her every other year.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

According to Rudder, the engine was a 24-hp Kermath with a “special chain drive to the propeller shafting, a method that has worked admirably.” The engine was replaced in 1975 with a 40-hp Universal Marine engine that suffered routine seizures. The propeller shafting was hardly “admirable” unless you were deaf—it was encased in a leaking, clanking, oil-filled shell. Nevertheless, if we were on deck, shivering in a cold, dying wind, Dad would turn on the “iron jib,” and we would crawl into either the port or starboard aft bunk to feel the warmth of the engine, which was heaven, despite the smell and the propeller shafting’s rhythmic clanking.

We had overnights as a family, too. More important, when we were growing up, we treasured those frequent nights in the harbor when she lay on her mooring off the neck and our parents would let us have friends spend the night on board. As on land, we played cards, laughed, and then fell into the bunks to talk some more until, one by one, we fell silent. Later, we graduated to strip poker and the boys learned to cheat. Soon there were nights without much talking and no cards. When shore life was too much, we would escape for the night to lie in one of the bunks, be rocked asleep by waves breaking off Southern Island, and then be woken up as the hull vibrated from the engines of the Miller brothers and other lobstermen as they headed out to pull traps, their wakes slapping against the hull.

Once Jamie Wyeth called and said he wanted to paint our boat. We told him we were pretty sure Linda had finished the varnishing, but he was more than welcome to help paint the topsides.

When our father died in 1970, our mother offered my siblings and me the boat. The decision was not hard. We were fortunate to have a boathouse on the neck (the “Shipyard”) that was designed especially for

Dyon, although the ways had never extended far enough. We fixed them and became the third generation of Smiths to preserve this unusual sloop.

Dyon

Dyon’s spacious interior is perfect

for large family gatherings aboard.

Photo by William Gorman

At the outset, we knew nothing about the care of a boat of this size on the size of our pockets. Over the years,

Dyon has acquired an extended local family of caretakers. Freeman Brewer, the foreman at Wayfarer who had been responsible for

Dyon, showed us how to build a proper cradle and how she should be hauled. Linda Tripp has supervised paint and varnish work.

Once Jamie Wyeth called and said he wanted to paint our boat. We told him we were pretty sure Linda had finished the varnishing, but he was more than welcome to help paint the topsides. Gary Price replaced the propeller shafting with a belt system free of oil and clanking, and also rebuilt the exhaust system. Mac Beam attends to the 1937 Chevy engine that runs the shipyard winch and other details of hauling and launching. Art Henry brings equipment to make sure she is far enough down the ways to float off on at least an 11-foot tide—

Dyon never seems to slide far enough. Then he steps the mast over at the late Tim Watt’s dock at the East Wind Inn.

Dyon is launched every other year. This gives us a rest and time to replenish our “blueberry funds.”

For

Dyon’s 90th birthday this year, we dipped into that blueberry money and gave the boat a serious update at Rockport Marine, including a new 50-hp Yanmar diesel engine. Taylor Allen instituted strict cost control and his wizard accountant knew how to work the spreadsheet with all sorts of “credits.” But the bottom line never seemed to shrink.

Dyon should be in good shape for a while, or we’re going back for a refund.

Dyon will once again slide down the ways this year, sometime in June. She will race at the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta in Brooklin, and drop anchor afterwards alongside her wooden friends. Don’t hesitate to come by and say hello.

Named after his grandfather and

Dyon’s original owner, Philip L. Smith II is a doctor who has practiced medicine at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore since 1972. He has come to Tenants Harbor every summer since 1945.

Photo by Alison Langley

By Maynard Bray

Ordering

Dyon from Luders Marine Construction Company, instead of from Geo. F. Lawley & Son or Herreshoff Mfg. Co. was a stretch for Philip L. Smith. He’d met A.E. Luders, Sr., at the New York Motorboat Show around 1923 and purchased from him three Red Wing daysailing sloops for his children to use at Tenants Harbor. Even though he liked the Red Wings, he was not sure about a bigger yacht.

“We had quite a job to finally convince him that we could build him a satisfactory [larger] boat,” wrote Luders in a memoir. Powerboats, not sailboats, were Luders’s specialty, so there was some risk. I expect that being allowed a major role in the design of

Dyon sold Smith on the concept. He was listed, along with Luders, as

Dyon’s co-designer right from the outset.

For the first years of her life,

Dyon was stored for the winter where she was built, at the Luders yard in Stamford, Connecticut, and sailed back and forth to Maine each spring and fall. By the 1930s, P.L. Smith found a place in Rockland, Maine, and stored her there. Smith soon became involved with rejuvenating that place and, with his investment, the yard, reorganized as Snow Shipyard, began to thrive. One after the other, a car ferry, wooden draggers, and a yacht or two, were finished and slid overboard. Then with the war, came submarine chasers, minesweepers and net tenders. Meanwhile,

Dyon’s covered storage remained secure. (This was when my father gave me my first glimpse of a “real yacht.”)

How much Luders and how much Smith went into

Dyon’s design is a question to which we may never know the answer, but their collaboration created one of the handsomest yachts of her size I’ve ever seen. The sheer, the flare of her topsides, the profiles of her bow and stern, and her round-fronted trunk cabin with its varnished top and painted, paneled sides are all in harmony with each other.

A close look at the interior of

Dyon’s hull reveals a combination of sawn and steam-bent frames supporting the planking. I’d guess that she was set up and planked over those wide-spaced sawn frames, after which the intermediate ones were bent in against the double planking and fastened. Luckily, all her screws and bolts are non-ferrous and her ballast keel is lead, so the rust that plagues so many aged yachts and shortens their lives isn’t a problem here.

Why

Dyon was given that big gaff mainsail I never understood. It seems to me that for her intended use as a daysailer, a Marconi yawl would have made more sense. Nowadays, that gaff sloop rig and the fact that she’s had no significant alterations in 90 years make her unique. You can’t miss her, whether she’s sailing, or lying to her Tenants Harbor mooring. And once you’ve seen her, she’ll long remain in your memory.

Maynard Bray is

WoodenBoat’s technical editor, a co-founder of the classic boat website OffCenterHarbor.com and author of many books and articles about boats.

Watch the Smith family launch

Dyon

from her specially-built boathouse and take her for a sail.

Video courtesy of William Gorman.

Dyon was designed by Bill Luders, with help from her owner P.L. Smith. This photo shows the newly finished yacht on her launching day in July 1924 at the Luders yard in Stamford, Connecticut.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

Dyon was designed by Bill Luders, with help from her owner P.L. Smith. This photo shows the newly finished yacht on her launching day in July 1924 at the Luders yard in Stamford, Connecticut.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

P.L. Smith, seen here at

the helm with his good friend Harold Foote,

sailed Dyon up and down

the Maine coast.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

P.L. Smith, seen here at

the helm with his good friend Harold Foote,

sailed Dyon up and down

the Maine coast.

Photo courtesy the Smith family

The bronze hawk on Dyon’s bow.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

The bronze hawk on Dyon’s bow.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

The Smith family has owned Dyon

for 90 years, ever since she was built. The wooden yacht

is kept in a large boathouse in Tenants Harbor, Maine,

where assorted family members help to paint and launch

her every other year.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz

The Smith family has owned Dyon

for 90 years, ever since she was built. The wooden yacht

is kept in a large boathouse in Tenants Harbor, Maine,

where assorted family members help to paint and launch

her every other year.

Photo by Benjamin Mendlowitz Dyon’s spacious interior is perfect

for large family gatherings aboard.

Photo by William Gorman

Dyon’s spacious interior is perfect

for large family gatherings aboard.

Photo by William Gorman

Photo by Alison Langley

Photo by Alison Langley