Harun’s Paradise, a small hotel and sailing center in Tuzla, near Istanbul, features a curved jetty and a fleet of locally built International 12 Footer Dinghies. The hotel hosts the annual George Cockshott Regatta, which is named for the British man who designed the boats.

Photographs by Alice Greenway

“She’s an experienced sailor,” I hear my husband assure Rifat Edin. “Her father has two sailing boats. Her grandfather….”

I wish there was some way to restrain him. I am a competent sailor at the tiller of my parents’ sturdy Herreshoff 12½ in North Haven, Maine. But sailing the tippy, 12-foot, clinker-built, mahogany dinghy that Rifat shoves off from his pier feels as much to me like riding a horse as sailing. The lively boat tosses, keels, rears, and pivots beneath us—sensitive and quick as a polo pony.

Photographs by Alice Greenway

Equally disorienting are the warehouses and cranes at the shipyards across the bay, and the fact that we are sailing at the edge of Istanbul, a city of at least 15 million people and the largest in Turkey. Between us and Istanbul’s off-lying Princess Islands, huge tankers and container ships wait their turn to travel up the Bosphorus, the strait that connects the Sea of Marmara to the Black Sea.

I am sailing one of 20 wooden dinghies Rifat keeps here at his family’s old summer place in Tuzla, which is at the very southeastern tip of Istanbul. Called Harun’s Paradise, it is run as a small hotel and small sailing center.

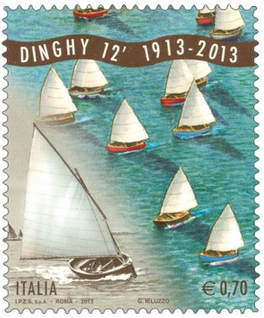

Rifat’s boats are built by local carpenters from a 1913 design by the British sailor George Cockshott. Known as International 12 Footers, they were early Olympic-class sailing dinghies that competed in the 1920 and 1928 games. Like Maine’s North Haven Dinghy, many of the boats in this class began life as tenders for bigger yachts, until their captains started racing one another.

I look up, taking my eye off the sail a moment. Caught in an uncontrolled jibe, my husband and I are bucked off, fully clothed, into the Sea of Marmara.

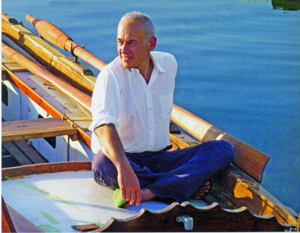

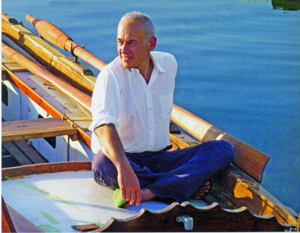

A tall, broad-shouldered man, Rifat is a restorer of wooden boats and old Istanbul houses. He has been a driving force in reviving the Cockshott dinghy, internationally as well as in Turkey. “These dinghies were popular in Turkey in the 1920s and 1930s,” he says. “In 1960, there were many. But then came the newer Lasers and other fiberglass boats and the class died.” As a boy, he remembers enviously watching older men racing the 12-footers at the nearby town of Erenkoy. “They wouldn’t let me on their dinghies,” he says—a sure-fire way of sparking a boy’s interest.

“What if a school from Maine wanted to bring

students out here for a summer abroad?” asks

Rifat Edin, who owns Harun’s Paradise. “They

could race dinghies, sail to the Princess

Islands, and visit Istanbul.”

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin

The boats are lively and keen, requiring constant adjustments of sail and weight, and frequent hiking out. It takes a sharp tug on an extra sheet called a tripping line to bring the rig around the mast at each tack. Sailing them is addictive. We stay the night at Harun’s Paradise, and I notice that Rifat’s boatman, George, and his cook, Hakan, seize any chance to take a spin. If it’s not too windy, Hakan sails to a market across the bay for food, eschewing his bike.

The sailing is challenging enough, but how to dock? Rifat’s pier is an angled stone jetty tucked between a fishing pier and a fleet of small boats. It is directly downwind. I look up, taking my eye off the sail a moment. Caught in an uncontrolled jibe, my husband and I are bucked off, fully clothed, into the Sea of Marmara.

A few minutes later we are plucked from the water by Rifat and George. Soon, we are sitting in a cozy room where Rifat holds court before a roaring fire and a large tray spread with Turkish cakes and hot tea.

Sailing a 12 Footer off Harun’s Paradise with the Princess Islands and Istanbul in the distance.

Photograph by Alice Greenway

When Rifat was a child, Tuzla was a sleepy, shady, seaside retreat. But Istanbul has grown ten times in size since 1960, expanding out along the Bosphorus and beyond. Today this neighborhood is a curious mix of small, low-rise industrial buildings, where some of Rifat’s carpenters work, set amid fancy houses, tennis clubs, and fish restaurants. In a few years, the underground Metro will arrive.

At Harun’s Paradise, Rifat manages to hold onto a piece of the past. There are 15 guest rooms, each in its own house or bungalow, furnished with eclectic antiques that range from an old pump organ to Ottoman marble wash basins and wood-burning stoves. But the heart of the place is sailing—

yelken in Turkish—along with boatbuilding and restoration. “Every big city needs a place like this, to breathe,” Rifat says.

“Harun is our Herreshoff,” Rifat explains. “His boats have the same attention to detail, and poetry-like solutions.”

Wandering through his ramshackle garden, you might stumble upon a finely carved wooden rowboat (

caique) with a passenger seat at the back. Built to ferry people across the Bosphorus, it was designed by the famous Turkish boatbuilder Harun Ulmen, for whom Rifat’s place is named. Harun sailed for Turkey in the 1936 Olympics. Up on stilts near the entrance to the garden rests a 50-foot Harun cutter, built in 1945, which Rifat is restoring. “Harun is our Herreshoff,” Rifat explains. “His boats have the same attention to detail, and poetry-like solutions.”

Fifteen-foot oars rest against a central watchtower that Rifat uses for his own house and library. Tables and chairs are spread about; the curved sides of wooden boats serve as benches. An ornate metal Ottoman chimney pipe is rigged to take smoke from a barbeque grill.

Along one of the meandering pathways, a jaunty banner heralds the final race of the 2013 George Cockshott Regatta for International 12s, which was held here in October. Rifat launched the regatta six years ago. “Welcome. Hosgeldiniz! 100th Anniversary of 12' Dinghy,” the banner reads.

“When I started building these dinghies,” Rifat explains, “I tracked down the great-great grandson of Cockshott, who now runs a sailing school in North Cyprus. The young Cockshott donated a silver cup his ancestor had won, which became the George Cockshott Trophy.” Last year, to Rifat’s delight, a young Turkish sailor Emrah Tasli won the trophy after races in Naples, Hamburg, Lucerne, Palermo, and Tuzla (Rifat placed fifth).

At present, the 12s are particularly popular in Italy and Holland, Rifat said. But as with the America’s Cup, there are disputes over design and rigging—heated disputes. According to Rifat, “The Dutch want their boats as simple as possible, to sail the way George Cockshott designed them.” The Italians, who have perfected the rigging and redesigned adjustable masts, have made the boats so sophisticated that they “almost want a hairdryer attached.”

George Cockshott, an amateur from Southport,

England, drew the 12 Footer plans for a 1912

competition for a sailing and rowing dinghy.

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin

“I think we have not yet reached our peak (of dinghy sailing). In the next five years, it will catch on more,” Rifat predicts. “People will get sick and tired of their big boats, which are difficult to manage and need a captain and crew and maintenance.”

An inveterate collector, who seems to attract people and stories as well as boats and artifacts, Rifat is currently restoring half a dozen boats. He has plans to revive kanjabas, a traditional Bosphorus workboat rowed by up to eight men and with a single sail. Last summer, he bought a 72-foot-long, copper-plated racing yacht, called the

Hildegarde, that once belonged to the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). Rifat is looking for old photographs so that he can restore it to its original layout.

As for me, I have learned the simple trick to docking at Harun’s Paradise. Sail downwind straight for pier. Then at the very last moment, swivel a sharp 180 degrees into the wind and lower the sail. If you happen to drift to one side, a few gentle tugs on the rudder will bring you back in.

Sailing a 12 Footer off Harun’s Paradise with the Princess Islands and Istanbul in the distance.

Photograph by Alice Greenway

. Her second,

, was published by Grove Press in January. She spent three months in Turkey after finishing her recent novel.

For more information on Harun’s Paradise go to

:

It’s important to note that the Turkish Dinghy fleet is part of a much wider revival that has been ongoing for over 20 years. The Dutch fleet has always been strong, but the previously strong Italian and Japanese fleets almost died in the 1970s. However, since the early 1990s fleets have been growing and it is now commonplace to see 100 or more boats competing at major regattas.

Italy, The Netherlands, and Japan remain the strongest countries, but fleets are growing in Switzerland, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Naturally, when Rifat Edin became interested in the Class we were pleased to help and provide encouragement. The events he has hosted have undoubtedly done much to bolster our international credentials. Rifat has a great deal of enthusiasm and has done wonders in re-establishing the Dinghy Class in Turkey.

New boats are being built around the world. I know of two boats currently under construction in the United States. Other boats have recently been completed in Argentina, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The most competitively priced dinghies are those constructed by boatyards in Lithuania and Turkey.

As an aside, the Italian Post Office issued a special postage stamp in 2013 to commemorate the centenary of the Dinghy Class!

The attempts to find descendants of Dinghy designer George Cockshott are quite interesting. During the 1980s and 1990s, dinghy historians went to great lengths to locate descendants, including advertising in the British yachting press and researching at museums, to no avail. It was Google that came to our rescue. When searching for the name Cockshott, I happened upon an Alex Cockshott who was an instructor at the Royal Yachting Association. Reasoning that the surname was not common and it was quite possible that an interest in boating had run in the family, I wrote to him. Alex turned out to be a great grandson of George. Through him I made contact with the rest of the family who had no idea that their grandfather’s boat had been so successful and still existed.

In fact, George had created a sailing 'dynasty'! One son was killed while commanding a yacht that was torpedoed during World War II. Another son had joined the RAF and represented them in sailing events. Grandson Chris runs a sailing school in Cyprus, granddaughter Jane sails a 43-foot yacht, great grandson Alex now operates a charter business in the Mediterranean, and a great-great grandson teaches sailing in Australia. None of them had sailed or even seen a 12-footer Dinghy.

Chris Cockshott donated a trophy that was originally won by his grandfather in the early at a West Lancashire Yacht Club sailing event. We now know the family well and some of them were guests of honor at the anniversary event at West Kirby last summer. See

The correct English term for the sail plan is a standing lug. The sheet that author Alice Greenway refers to in her article “Harun’s Paradise” is used to transfer the gaff from one side of the mast to the other when tacking is called a tripping line.

The organization has a website at

and are active on Facebook, where event details can be found.

Steve Crook is President of the International Twelve Foot Dinghy Class Association. An Englishman living in Switzerland, Steve started sailing National 12-foot Dinghies in England in 1966 but graduated to the International class in 2007.

Harun’s Paradise, a small hotel and sailing center in Tuzla, near Istanbul, features a curved jetty and a fleet of locally built International 12 Footer Dinghies. The hotel hosts the annual George Cockshott Regatta, which is named for the British man who designed the boats.

Photographs by Alice Greenway

Harun’s Paradise, a small hotel and sailing center in Tuzla, near Istanbul, features a curved jetty and a fleet of locally built International 12 Footer Dinghies. The hotel hosts the annual George Cockshott Regatta, which is named for the British man who designed the boats.

Photographs by Alice Greenway Photographs by Alice Greenway

Photographs by Alice Greenway  “What if a school from Maine wanted to bring

students out here for a summer abroad?” asks

Rifat Edin, who owns Harun’s Paradise. “They

could race dinghies, sail to the Princess

Islands, and visit Istanbul.”

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin

“What if a school from Maine wanted to bring

students out here for a summer abroad?” asks

Rifat Edin, who owns Harun’s Paradise. “They

could race dinghies, sail to the Princess

Islands, and visit Istanbul.”

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin Sailing a 12 Footer off Harun’s Paradise with the Princess Islands and Istanbul in the distance.

Photograph by Alice Greenway

Sailing a 12 Footer off Harun’s Paradise with the Princess Islands and Istanbul in the distance.

Photograph by Alice Greenway  George Cockshott, an amateur from Southport,

England, drew the 12 Footer plans for a 1912

competition for a sailing and rowing dinghy.

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin

George Cockshott, an amateur from Southport,

England, drew the 12 Footer plans for a 1912

competition for a sailing and rowing dinghy.

Photograph courtesy Rifat Edin