Mealtime aboard the famous fishing (and racing)

schooner

Gertrude L. Thebaud

in 1932. Harry Eustis (front right) served

most of his time aboard schooners as a cook.

Jack Mayo, another well-known Gloucester cook,

is in the background.

Photographs courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

By Sandra L. Oliver

“It don’t do to scrap with the cook,” foremast hand Jimmy Marshall said to his shipmates aboard the downeaster A.J. Fuller at the end of the 19th century. “I knowed a cook once wot—blanked—in the soup an’ bully on an English bark,” he said, leaving to our wildest imaginations the details of what the cook did to the soup and bully. According to Jimmy, the skipper got wind of the incident and put the cook in irons, but not for long. He had to be set free because he was the only one who could... well... cook!

That story made a big impression on the young Felix Riesenberg, who went to sea at age 16. He later recorded his adventure in the book,

Under Sail. Stories about the abuse sea cooks took and gave, and the kindnesses they often showed crew-members, are common in memoirs and narratives of life at sea such as Riesenberg’s, who recorded Jimmy Marshall’s story.

Food aboard a cargo-carrying or fishing vessel was so important to morale and energy that the member of the crew who prepared it held tremendous responsibility.

Finding someone able to cook was one of thing; finding someone willing to do the job was another.

These meals were hardly complex fare: boiled salt beef or pork, boiled potatoes or peas, hardtack, the occasional simple, boiled pudding called duff. Repairing rigging, mending sails, maintaining the vessel, and navigating all were much more complex tasks and required more skill than cooking. Even the steward, the captain’s servant whose job included preparing food for the cabin, had more challenging culinary tasks than the cook. Stewards made yeast, and baked bread and pies. They even roasted chicken.

Rockport, Maine, artist Carroll Thayer Berry

took this photo of a cook in the galley

of the windjammer

Mabel in 1952.

Finding someone able to cook was one thing; finding someone willing to do the job was another. Until the early 1900s, cooking ashore was primarily women’s work, except in some branches of the military and at sea. Armies on the march and even in camp, followers notwithstanding, established messes—that is, small groups of men who ate together—and cooked their own rations, sometimes taking pride in their capabilities, and sometimes cooking under duress. One day in October 1775, for example, Samuel Hawes, a Continental soldier from Massachusetts, wrote in his journal, “Nothing remarkable this day, onely (sic) I was chose to cook for our room consisting of 12 men and a hard game, too.”

In the 19th century, surf men for the Life-Saving Service, stationed on lonely stretches of beach or remote shorelines, were expected to take turns doing their own cooking. They were often not happy about it. In 1889, the station keeper at the Truro, Massachusetts, station wrote to his superintendent, saying that two of the crew wanted to be excused from cooking duties. The superintendent wrote back, saying that the keeper would just have to work it out, because by equipping the station with cooking gear, the government implied that it expected the men to take care of their own food preparation.

At some life-saving stations, married men invited their wives to join them for the weeks they had cooking duty, but sea cooks didn’t have that option. By the mid-1800s, most owners of American sailing ships could not convince Yankee men to cook. Instead, they employed black cooks and, a little later, Asians. The pay rates of cooks declined as more non-whites entered the occupation. To make things worse, the cook was often the butt of racially motivated practical jokes, even when the crew had to rely on his good graces.

Passengers on the pleasure yacht

Olwyn

enjoyed a bountiful meal during a 1906 sail

along the coast.

The cook, sometimes nicknamed “Doctor,” for all his abuse, could allow a man with wet socks to hang them up to dry by the galley stove, or might prepare something a little extra for a sick sailor. Charlie Abby, in his sea journal which was quoted in

Before the Mast in Clippers, by Harpur Allen Gosnell, recalled little servings of rice that the cook fixed for him when he was sick and couldn’t tolerate any other food. Wise sailors ingratiated themselves with the cook by chopping kindling for the stove and causing him no trouble.

On smaller vessels engaged in coastwise trades, such as schooners carrying goods from New England to southern ports or the Caribbean islands, the cook’s duties were fairly light and included helping to sail the vessel. In the early days, boys from ten years old and up into their early teens went as cook on these vessels, and on fishing vessels, too, where their galley skills need not have exceeded making chowder. Samuel “Bully” Samuels, captain of the famed clipper

Dreadnought, first went to sea at age 11; his career included a stint as cook. In his memoir,

From Forecastle to Cabin, he wrote that he learned from the skipper’s sister how to fry fish and ham, and to bake cornbread and biscuits.

Cooking was all right for boys, but some men felt demeaned, or at least a little self-conscious, doing what many saw as women’s work. A former store clerk on the Blue Hill peninsula who went to sea on a coaster in the late 1800s recorded in his journal that his mother and sisters would be amazed, maybe amused, to see him baking bread. Sixteen-year-old Ben Ely, a sailor before the mast aboard the whaleship

Emigrant, was recruited as steward. After learning what he called “the useful accomplishments in the line of housewifery,” he appealed to the captain to let him return to the fo’c’sle, and the captain agreed.

After learning what he called “the useful accomplishments in the line of housewifery,” he appealed to the captain to let him return to the fo’c’sle, and the captain agreed.

On fishing vessels in the late 1800s and later, however, it was a different story. Cooks were highly respected and well paid, often earning a wage close to that of the captain, and they weren’t necessarily the youngest on board. In the 1920s, for example, Wesley George Pierce from Southport, Maine, was 57 when he went to sea as cook late in his fishing career.

Cooks aboard fishing vessels worked hard, providing meals for as many as 12 to 20 men, at least three and sometimes four times a day. They also had to put up enough coffee for “mug-ups” and grub for the “shack cupboard,” where leftovers and extras were stashed for the men to snack on between meals. Meat and potatoes, soup, cake, cookies, pie, bread, biscuits, and puddings, and lots of them, comprised the repertoire. Wesley George Pierce reported in his memoir,

Goin’ Fishing, “[The cook] makes his own bread, baking eight loaves a day, makes pies by the dozen, fries doughnuts, half a bushel at a time, makes puddings of various kinds, bakes cake of several kinds, and often frosts them.”

Shipboard stovetops, like this one on the

Arctic-exploring schooner

Bowdoin

in 1937, featured rails to keep pots from

slipping off in rough weather.

When Pierce shipped as cook aboard the steam-powered mackerel purse seiner

Lincoln, in 1926, he had to fit out the galley for a three week voyage. “Skipper,” he said to the captain, “I should like to order some fruit for the trip, a few bananas, oranges, and grapefruit, if you are willing.” “Cook,” the captain said, “get anything you want.” There was no argument on that fishing vessel.

“A cook who understands his business and knows how to cook well, can set a fine table,” Pierce wrote. “The fishermen expect it, and if you are unable to give it to them, the ‘Old Man’ (skipper) will ‘turn you ashore’ and ‘ship a new cook.’”

For their part, fishermen kept on the good side of the cook. They emptied slops when the cook’s bucket filled up; delivered a cleaned and chunked up fresh cod or haddock for chowder when requested; and avoided making a mess or getting in the way.

Sandra L. Oliver’s most recent book

Maine Home Cooking: 175 Recipes from Down East Kitchens (Down East Books, Rockport) was published in 2012.

Soft Molasses Cookies

Maine fisherman Charlie York remembered a sword-fishing trip in 1902 and a cook named Steve who made, “fresh doughnuts, molasses and sugar cookies regularly.” York described Steve as a true “glutton for punishment,” since making enough cookies to meet the big appetites of fishermen was a tremendous chore.

These cookies are the sort that Steve might have made. The recipe came to me from Virginia Leavitt, married to Mainer John F. Leavitt, who sailed on Maine coasting schooners in the early 20th century. John devoted his retirement to maritime art and recording the history of downeast schooners; his Wake of the Coasters is a classic. Virginia obtained the recipe from John’s mother, Grace, who grew up in Norway, Maine.

On board a fishing vessel, the cook no doubt used bacon fat for shortening. Whether you do or not is up to you. Melted butter or shortening works, too.

Ingredients:

4 cups of flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

¼ teaspoon ginger

¼ teaspoon cloves

¼ teaspoon cinnamon

1 cup sugar

1 cup melted bacon fat

1 cup molasses

2 Tablespoons vinegar

2 Tablespoons cold water

Preheat the oven to 350°. Sift together the flour, baking soda, and spices. Mix together the fat, sugar, molasses, vinegar, and water. Beat together. Gradually add the wet ingredients to the dry ingredients, mixing quickly and thoroughly. Drop spoonfuls of dough on a greased baking sheet. Bake ten to twelve minutes, or until the centers feel firm to the touch. Cool.

—Makes about 48 three-inch cookies.

Mealtime aboard the famous fishing (and racing)

schooner Gertrude L. Thebaud

in 1932. Harry Eustis (front right) served

most of his time aboard schooners as a cook.

Jack Mayo, another well-known Gloucester cook,

is in the background.

Photographs courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum

Mealtime aboard the famous fishing (and racing)

schooner Gertrude L. Thebaud

in 1932. Harry Eustis (front right) served

most of his time aboard schooners as a cook.

Jack Mayo, another well-known Gloucester cook,

is in the background.

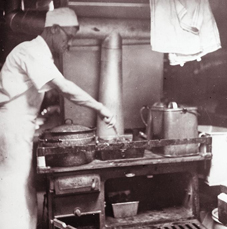

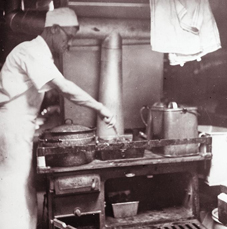

Photographs courtesy Penobscot Marine Museum Rockport, Maine, artist Carroll Thayer Berry

took this photo of a cook in the galley

of the windjammer

Mabel in 1952.

Rockport, Maine, artist Carroll Thayer Berry

took this photo of a cook in the galley

of the windjammer

Mabel in 1952.  Passengers on the pleasure yacht Olwyn

enjoyed a bountiful meal during a 1906 sail

along the coast.

Passengers on the pleasure yacht Olwyn

enjoyed a bountiful meal during a 1906 sail

along the coast. Shipboard stovetops, like this one on the

Arctic-exploring schooner Bowdoin

in 1937, featured rails to keep pots from

slipping off in rough weather.

Shipboard stovetops, like this one on the

Arctic-exploring schooner Bowdoin

in 1937, featured rails to keep pots from

slipping off in rough weather.