Painter Jon Imber, shown here in his studio, can no

longer get to his favorite landscape vantage points.

Instead, he has been painting portraits, as many as

one a day. That’s his wife, artist Jill Hoy, painting

in the background.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

By Carl Little

On a Monday morning in late September, painters Jill Hoy and Jon Imber sit in the sunlit front room of their house on Thurlow Hill, on the curving stretch of Route 15 that sweeps down into Stonington village. Flowers and grapes decorate the kitchen table, and the art on the walls includes a new Imber portrait, as well as one of Hoy’s coastal paintings dedicated to her father, who died in July. The couple’s dog, Ella, keeps an eye on the front door.

As one visitor arrives, another leaves: neighbor Sherry Sansing has just brought over dinner for the couple. Her joke that she always leaves town after dropping off food “in case it’s bad” is greeted with laughter. Before leaving, she looks Imber in the eye and demands that he not stop painting until Columbus Day. “I’m coming back for my portrait, so don’t go anywhere,” she says.

Sansing smiles as she makes her comment, but both she and Imber know she is serious.

Last summer Imber was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, a devastating affliction that slowly paralyzes the body. In the year since the diagnosis, the 63-year-old painter has lost much of the use of both his hands, and now walks and speaks with increasing difficulty. But the adversity has not set back his creative spirit. If anything it’s made him even more determined to paint. And paint he does: 80 portraits of friends and family encircle his adjacent studio, all created in the past three months or so, nearly one a day.

Imber has adapted to the increasing loss of mobility, first by shifting to his left hand to paint (he is right-handed) and then by using both hands clutched together to hold the brush.

The adversity has not set back his creative spirit. If anything it’s made him even more determined to paint.

The portraits are a direct result of the ALS. Unable to make his way to favorite landscape vantage points in Stonington to practice the energized version of

plein air painting for which he is best known, Imber has been mostly confined to his studio. So when somebody walks in to pay a visit, he says, “Hey, sit down, let’s do a portrait.”

Hoy, a well-known landscape painter herself, also has shifted her routine toward staying inside with her husband, helping him to eat and to walk, as well as to paint. This new phase in a 20-plus-year relationship of love and respect has tested the two, but they carry on. After all, there is still a lot of painting to be done, says Imber.

Since being diagnosed with ALS last year, Imber has lost the use of first his right hand, then the left. Now he uses a specially adapted brush, holding it in one hand and steadying it with the other, then guiding it with thrusts that begin at his feet and move up through his whole body.

On this September morning, Imber sits at the kitchen table, his arms on lobster buoy armrests that a neighbor rigged. He and Hoy take turns talking about their lives together and their commitment to art.

The two met in 1991 at the barn studio of Karl Schrag, a New York City painter who spent much of every summer from the 1950s until his death in 1995 on Deer Isle, painting landscapes in his signature expressionist style.

One thing led to another—a first date at the Blue Hill Fair, conversations about art and aesthetics, an invitation to see Imber’s pastels—and they began to get serious. Imber was teaching drawing one day a week at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at the time. He would drive up between classes to visit. “I restrained myself and waited until Christmas to propose,” he recounted. “And then Jill restrained herself and waited till May to accept.”

This new phase in a 20-plus-year relationship of love and respect has tested the two, but they carry on.

Hoy grew up summering on Deer Isle. Her father, an English professor at Wesleyan College in Connecticut, rented Lazy Gut Island, off the Sunshine section of Deer Isle, and then purchased a ship captain’s house in the village in 1964. At that point she became a painter, “with an appreciation,” she has written, “of architecture and gardens, as well as light, energy, pattern, flow, and the documentation of place.”

Racing against time, Imber has been painting as much as he can and said he’s never felt better about himself as an artist. “Make sure the curator at the Louvre Museum reads this story,” he said, only partly in jest.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

After attending the University of California, Santa Cruz, Hoy spent a dozen years in New York City before moving to Somerville, Massachusetts. When her father’s Deer Isle house was sold, she rented places in Stonington until she and Imber purchased their home in 1994.

Imber had been coming to Maine on “painting vacations” before he met Hoy. Born on Long Island, New York, he earned a BA from Cornell University. A year after receiving an MFA from Boston University in 1977, he was given his first big show at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum. He went on to exhibit at Nielsen Gallery, one of Boston’s top galleries, and taught at the Rhode Island School of Design, the School of Visual Arts in New York City, Mass Art, and Harvard (for 27 years).

Like Schrag and many other artists, Hoy and Imber divide their time between Maine and elsewhere (in their case, Somerville, Massachusetts) where they are members of an artists’ co-op located in a former wood-frame factory building. Imber finds the setting more tranquil than Stonington, where their home fronts a busy road.

A recent Imber self-portrait.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

While Hoy focuses on the landscape when in Maine, she turns inward in the winter, painting figural work and fantasies based on “seminal sightings,” many of them originating in Stonington, such as a happening organized by performance artist Lila Roo on Government Rock or a parade of New Orleans musicians in town for the jazz festival organized by the Opera House Arts. Several of these paintings were on view in September in a pop-up show at Michael Connors’ Eagle Art and Antiques shop in Stonington.

A visit to Hoy’s gallery/studio on Main Street reveals the full breadth of her landscape vision: lobsterboats at anchor, vivid autumn blueberry barrens and a sunset from nearby Caterpillar Hill. Aside from a few fog pieces, the canvases are light-filled and often dazzling.

Known as a colorist, Hoy looks for what she calls the “subtext” colors in a tide pool, granite ledges, a garden, the sea. “What is the color embedded in the color?” she asks herself. It might be a pink, a pale orange, or Prussian blue, and she will let the color come to the surface and vibrate. Color is “enlivening, startling to us,” she notes; it helps you “wake up to the world.”

Imber, too, lives by the landscape. He credits his wife with introducing him to some of his favorite places in the area (back in his more mobile days, they sometimes painted the same spot). “I figure as long as there’s good information out there, like flowers and sky and sea with a couple of rocks,” Imber said, “I can figure out something to get me going and then I’ll just rely on my reactions and try to make it an exciting painting.”

Jill Hoy, shown here painting in

Stonington, Maine, last fall, is known

for her bright, plein air landscapes.

Since Imber’s diagnosis, she has spent

much of her time in the studio

helping him. Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Last May, Imber was the subject of a retrospective at the Godwin-Ternbach Museum at Queens College in New York. The 44 paintings in “PALAEMON: A Survey of Paintings by Jon Imber” highlighted the artist’s evolution from figure pieces to portraits to landscapes to abstract pieces.

The show reflected Imber’s influences, from the figurative work of his BU teacher and mentor Philip Guston to the abstract-expressionist energy of Willem de Kooning. In a review of the show in the

Boston Globe, art critic Sebastian Smee noted that it has never been “either/or” for the artist. Imber, Smee wrote, “has wrestled with different influences, different styles, and different subject matter all his life” leading to shifts in approach that are “less tectonic than nimble, supple, full of yearning and mischief.”

Hoy painted this luminous work, entitled “Weeping,”

after her father’s death last summer.

Imber derives energy from art of the past, be it Giotto, Ferdinand Leger, or Fairfield Porter. “Most artists are afraid to take on major influences after they achieve success with a quote ‘style,’” he noted. He believes that incorporating different influences has kept his work fresh and moving.

The most recent painting in the Queens College show was a self-portrait painted with the left hand. “I try not to look too grim,” Imber explained, “but unfortunately it has a somber cast to it.” As if to balance that solemnity, the survey also featured several still lifes of flowers, energized landscapes, and the delightful “Gabe the Bullfighter with Flapdoodles (El Cordobés de Somerville),” a portrait of the couple’s son Gabriel at age two (he is now 19 and attends Bates College).

Flapdoodles, a brand of children’s apparel that features curlicues, inspired Imber to paint a self-portrait wearing these “kind of ridiculous-looking pants.” As seriously as one takes the whole enterprise of painting—and life—“if you don’t have a sense of humor, you’re finished,” he explained.

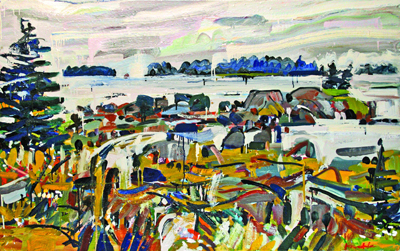

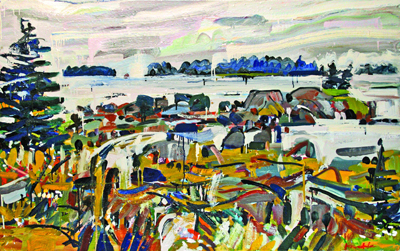

One of Imber’s earlier oil landscapes,

“View of Thoroughfare,” 30" x 48"

Courtesy of the gWatson Gallery

In his Stonington studio, surrounded by his new portraits, Imber speaks frankly about his condition and its impact on his art. When he shifted to painting with his left hand, he discovered just how much the brain controlled his movement. His left hand takes orders “pretty well,” he says, but the process isn’t that practical or as precise.

Despite his new limits, Imber has managed to achieve a new lyricism.

“If I make what I would have called a mistake, like the hair kind of wild [in a portrait],” he explained, “it’s not the way the hair looked, but what I was capable of painting—better than the real thing.”

The portraits are loose yet recognizable. This visitor immediately picked out likenesses of Stonington residents Ted Ames, whose studies of the lobster fishery earned him a MacArthur “genius” grant, and his wife, Robin Alden, executive director of the Penobscot East Resource Center. There are neighbors, fellow artists and family.

“It’s like a late phase,” Imber said, “painting portraits from life. So I’m amazed I’m spreading off into a new territory, 16 months since my ALS diagnosis.” He’s on a roll, and the portraits still look “Imbery” to him.

Asked how it has been, living together as two artists, Hoy described a “bedrock understanding of where we’re both coming from, our love” and the core commonality of their artistic vision. “It has been a great working relationship,” she said, one of mutual influence and attraction, and support. That each is the other’s greatest champion will help them face the challenges ahead.

Carl Little’s latest book is Nature & Culture: The Art of Joel Babb (University Press of New England). He lives and writes on Mount Desert Island.

Artist Details

Imber is represented by gWatson Gallery in Stonington, Greenhut Galleries in Portland, and Alpha Gallery in Boston. He will have a show at the Danforth Museum in Framingham, Massachusetts, in March 2014. Hoy has maintained her own gallery in Stonington since 1984. She is a member of Art Collector Maine, and shows at Thos. Moser in Freeport, Gallery at the Grand in Kennebunk, and Lincolnville Fine Art.

Online Extras: VIDEO

From the Maine Masters film series, "Jon Imber: Virgin Territory" (working title) is a work-in-progress about how an artist, one of the important artists of our time, brought a community together to celebrate life in the midst of his dying. It is a story about each one of us and the humor and courage we can draw on to deal with our own mortality. View the 6-minute video clip here.

Video courtesy of Kane-Lewis Productions. Filmmaker Richard Kane of Sedgwick has been filming Imber in his studio for a documentary as part of the ongoing Maine Masters Series.

Online Extras: SLIDESHOW

Online Extras: SLIDESHOW

Jon Imber’s studio is filled with recent portraits of friends and visitors, as well as botanical subjects, which were all painted with his left hand.

Painter Jon Imber, shown here in his studio, can no

longer get to his favorite landscape vantage points.

Instead, he has been painting portraits, as many as

one a day. That’s his wife, artist Jill Hoy, painting

in the background.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Painter Jon Imber, shown here in his studio, can no

longer get to his favorite landscape vantage points.

Instead, he has been painting portraits, as many as

one a day. That’s his wife, artist Jill Hoy, painting

in the background.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Since being diagnosed with ALS last year, Imber has lost the use of first his right hand, then the left. Now he uses a specially adapted brush, holding it in one hand and steadying it with the other, then guiding it with thrusts that begin at his feet and move up through his whole body.

Since being diagnosed with ALS last year, Imber has lost the use of first his right hand, then the left. Now he uses a specially adapted brush, holding it in one hand and steadying it with the other, then guiding it with thrusts that begin at his feet and move up through his whole body.  Racing against time, Imber has been painting as much as he can and said he’s never felt better about himself as an artist. “Make sure the curator at the Louvre Museum reads this story,” he said, only partly in jest.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Racing against time, Imber has been painting as much as he can and said he’s never felt better about himself as an artist. “Make sure the curator at the Louvre Museum reads this story,” he said, only partly in jest.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

A recent Imber self-portrait.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

A recent Imber self-portrait.

Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Jill Hoy, shown here painting in

Stonington, Maine, last fall, is known

for her bright, plein air landscapes.

Since Imber’s diagnosis, she has spent

much of her time in the studio

helping him. Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Jill Hoy, shown here painting in

Stonington, Maine, last fall, is known

for her bright, plein air landscapes.

Since Imber’s diagnosis, she has spent

much of her time in the studio

helping him. Photographs by Jeff Dworsky

Hoy painted this luminous work, entitled “Weeping,”

after her father’s death last summer.

Hoy painted this luminous work, entitled “Weeping,”

after her father’s death last summer.

One of Imber’s earlier oil landscapes,

“View of Thoroughfare,” 30" x 48"

Courtesy of the gWatson Gallery

One of Imber’s earlier oil landscapes,

“View of Thoroughfare,” 30" x 48"

Courtesy of the gWatson Gallery

Online Extras: SLIDESHOW

Jon Imber’s studio is filled with recent portraits of friends and visitors, as well as botanical subjects, which were all painted with his left hand.

Online Extras: SLIDESHOW

Jon Imber’s studio is filled with recent portraits of friends and visitors, as well as botanical subjects, which were all painted with his left hand.