It’s 4:50 on a snowy Monday morning. Allison Watters wheels her Subaru up the semi-plowed drive of the low-slung former restaurant on Acadia Highway in East Orland that is the studio of WERU-FM. She has been making the 25-minute, early Monday-morning trek to the station for 13 years, and today’s weather is nothing compared to that first extra-snowy year when she lived in a cabin and had to ski down a long logging road just to get to her car.

The station is quiet. The overnight public affairs programs are going out over the air, but the regular staff isn’t due for a few hours yet. Knocking the snow off her feet, Watters loads music into CD players, cues the first cut, and formally starts WERU’s live broadcasting day. An hour of mostly instrumental music will give her time to make breakfast, get a cup of tea, and hit the music library.

Watters is typical of the volunteer programmers (if any are typical) at WERU. In real life, she has two kids, an understanding spouse, and a job sewing marine canvas. She has rearranged her life so she can have radio airtime. She loves the magic of live radio—being in a studio behind a soundproof door, surrounded by glowing meters, an array of CD players, record players, computers, flashing phone lines, log books, and electrical devices.

Watters joined the station in 2000 at the invitation of a musician friend who had been doing a morning show. “He had an opportunity to get a paying music gig in Jackson, Wyoming, and I’ve been here ever since.”

At precisely 6 a.m. Watters is back in the studio with a stack of music. She opens the mic and goes on the air live. “Good Morning! Welcome to WERU and Morning Maine!”

WERU has been broadcasting its uniquely quirky mix of talk, music, and news for 25 years, anchoring a community of volunteers as well as one of listeners. When the station began in the 1980s, most Maine radio stations fit a set format. Listeners would have found the ubiquitous Casey Kasem counting down the week’s American Top 40, the dulcet sounds of Public Broadcasting’s classical music, the curious astrological predictions of the “Cosmic Muffin” (where Mercury apparently was perpetually in retrograde), perhaps some industrial strength preaching on the Christian WHCF, or the diverse rock of WTOS, the mountain-top powerhouse. These formats certainly had their fans, but none involved a neighborhood station where the community could create its own programming.

The station has no dictated playlist. On-air hosts draw on WERU’s 70,000 CD library, the LPs down in the cellar (known as Vinyl Haven), and their own collections, downloads, and audience requests, interspersed with news, weather, and short spoken-word features. “I like to start off quiet and then rock out from 8 to 9,” says Watters. “It’s funny; I meet all these people who tell me that they spend their morning with me.”

Naomi Schalit, Executive Director and Senior Reporter for the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, calls WERU “locally grown, whole grain, unbleached and unadulterated radio that’s made by real people. It’s the pot-luck supper of Maine radio—and I love it!”

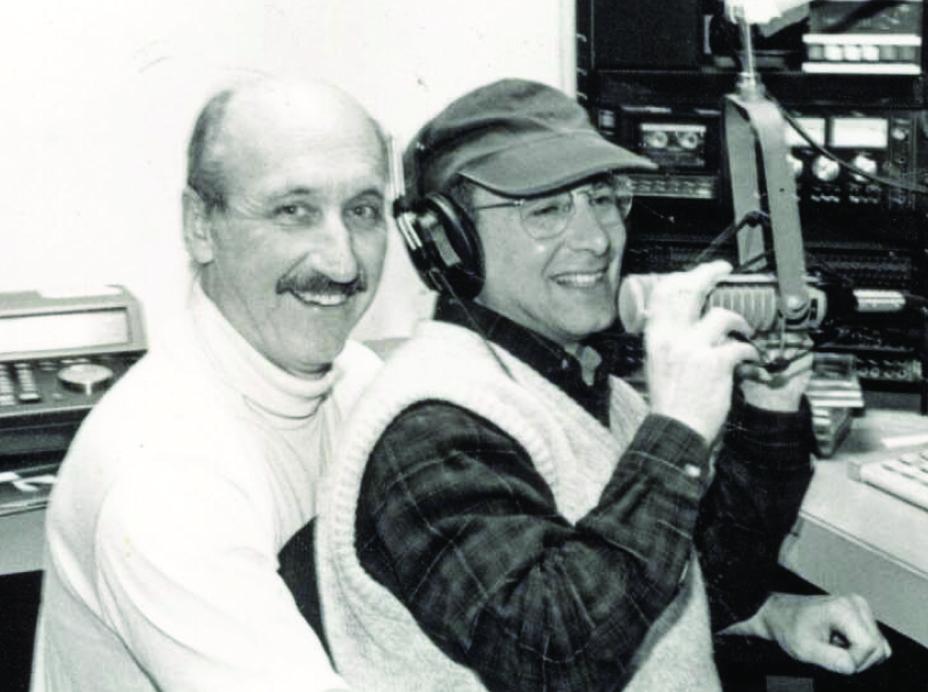

Singer-songwriter Noel Paul Stookey, on the left, helped come up with the idea for a community radio station, and in the early days held on-air concerts to raise money. Courtesy WERU (5)

Singer-songwriter Noel Paul Stookey, on the left, helped come up with the idea for a community radio station, and in the early days held on-air concerts to raise money. Courtesy WERU (5)The original notion for the station was hatched at singer-songwriter Noel Paul Stookey’s New World production studio, located in an old chicken coop in Blue Hill. The initial idea was for a “good news station” with a focus on Christian music. Over time, the concept evolved to a volunteer-run station that emphasized the positive, was part community theater, part local newspaper, part soap box for speeches, and part downtown bandstand.

The station applied for a license as a full-power, non-commercial station of 15,000 watts. This meant, given its location atop Blue Hill, that it could broadcast from Washington County to Lincoln County along the coast, inland to Bangor and Waterville and out to ships at sea. The idea was to fund it primarily through memberships, program underwriting, and a few grants. No one really knew if listeners would send in money for something they could get free on the air. But the ace in the hole was that this was not just radio you listened to; it was radio that you could participate in.

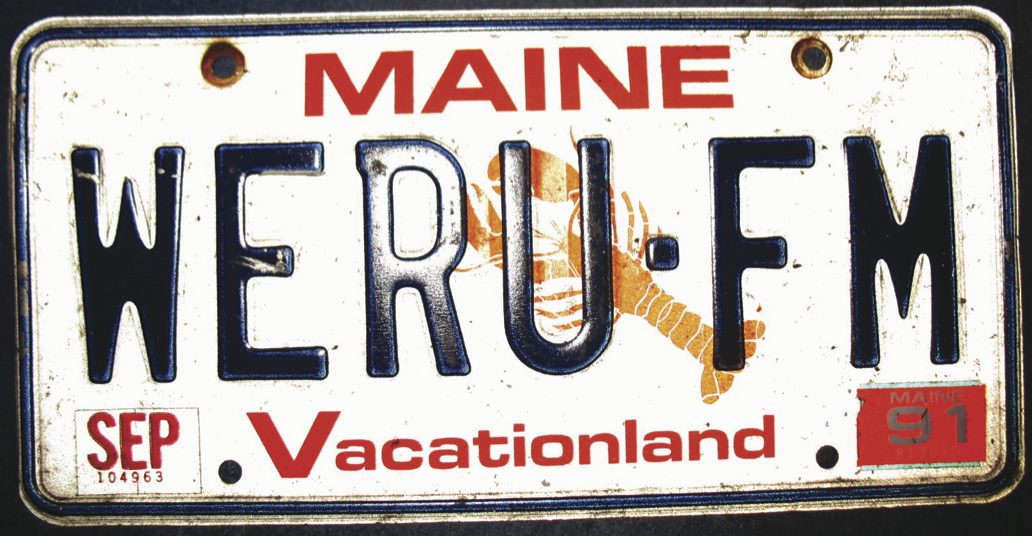

The choice of iconic WERU call letters was a result of good luck. The Federal Communications Commission sent up a list of available letter combinations. Nothing really stood out until someone noticed the serendipitous “We are you.”

Many notable musicians, writers and others have visited the station over the years, including Arlo Guthrie who arrived in his touring bus. The station has since moved out of the three-story Henhouse.David J. Snyder, who had been hired to work as an animator at New World but had some radio experience, was tasked by Stookey to help make the station a reality. Eventually Snyder became the station’s program director and cobbled together the format and schedule that still is unique to WERU.

Many notable musicians, writers and others have visited the station over the years, including Arlo Guthrie who arrived in his touring bus. The station has since moved out of the three-story Henhouse.David J. Snyder, who had been hired to work as an animator at New World but had some radio experience, was tasked by Stookey to help make the station a reality. Eventually Snyder became the station’s program director and cobbled together the format and schedule that still is unique to WERU.

In its early days, the fledgling organization tried to generate interest, buzz and money by hosting concerts by Stookey and his music industry friends. But by the autumn of 1987, the station still wasn’t built and money was running thin. And time was running out on the FCC construction permit. With the prospect that WERU might flounder before even broadcasting its first signal, organizers contacted Washington attorney Stephanie Summers who got the FCC permit extended. The station then doubled down on fundraising. A loan from a local bank was secured, and Snyder began an orchestrated scramble to build the studio at what became known as the Henhouse, in Blue Hill Falls.

A transmitter and a prefabricated radio shack were delivered by helicopter on a chilly day in March.

On a rainy afternoon, May 1, 1988, radios across midcoast and downeast Maine were tuned to 89.9 FM for a gala sign-on party. But inside the newly completed WERU studio, the staff was anxiously following events farther south. Attorney Summers was en route with the license that would allow legal broadcasting, which she had personally picked up from the FCC. She was hand-carrying it from Washington D.C., headed north on a flight through the lousy weather to Bangor.

A crowd had gathered outside the radio station in the rain. A band was ready to play on a flatbed truck stage and kids danced around a big May Pole. A giant ceremonial power switch was at the ready. Still no license. Then, with 20 minutes to spare, Summers wheeled into the dooryard.

The license was mounted on the studio wall and the ceremonial switch was pulled. With Maine comedian Tim Sample as emcee, live bagpipes in the background, and the crowd shouting a hearty station ID, WERU was officially on the air.

There were still a few glitches to be resolved. Within hours, the station learned that its signal was bleeding over the audio of a TV station in Blue Hill village, just in time to interfere with the dramatic concluding episode of Magnum PI. The station shut down for the evening and volunteers installed hundreds of emergency antenna filters. The station still had only one studio and no money to build a second one to use for production and training. That led to a most unusual schedule of going off the air every afternoon from 1-6 p.m. for training and production. That situation was eventually cured with funding from a federal grant. When the station moved its studio from a converted chicken coop in Blue Hill to new quarters in Orland, the operation got a fancy new sign, shown here behind volunteers, including the author (back row, second in from the right) and staff.

When the station moved its studio from a converted chicken coop in Blue Hill to new quarters in Orland, the operation got a fancy new sign, shown here behind volunteers, including the author (back row, second in from the right) and staff.

Fast forward to today: much has changed at WERU, and yet much has remained the same. The station has moved from a funky place that raised chickens (Stookey’s henhouse) to a funky place that cooked them (the ex-restaurant in Orland). The first transmitter, which served faithfully for 25 years while being gently nursed, cajoled, and given repeated CPR by engineer extraordinaire Bruce Clark (occasionally using Korean War surplus parts), has been replaced by a state-of-the-art solid-state transmitter. A smaller secondary transmitter serves downtown Bangor and the station also streams its programming digitally. Folks can now listen on their wireless device or smart phone. Public affairs editing is now done digitally rather than with a grease pencil and razorblade on reel-to-reel tape machine. Gone are the eight-track tapes for pre-recorded messages; those now live on a computer. National news reports and the weather no longer depend on the prompt delivery of the Bangor Daily News; the station is connected to the world by Internet and satellite dish.

Some things have not changed, though. The station is still volunteer-powered. Station manager Matt Murphy noted, “The station’s mission of providing a service to the community that is unavailable anywhere else in the media has remained essentially unchanged over the years.”

It takes a lot of horsepower to run a community radio station. A dedicated paid staff of seven keeps the infrastructure humming while some 300 volunteers—show hosts (a.k.a. DJs), news reporters, librarians, building maintainers, fund raisers, tech geeks, and good old-fashioned house cleaners—do the rest. “They really are a cross section of the community,” said Murphy, “ranging in age from 14 to 81. They are teachers, attorneys, lobsterwomen, midwives, pharmacists, boatbuilders, carpenters, acupuncturists, real estate agents, scientists, farmers, sign painters, professional photographers, and even a tattoo artist.”

The station’s news and public affairs division, headed up by news director Amy Browne, with a team of volunteer moderators and news reporters, works on a shoestring budget. Still, the station has managed to cover local issues such as the proposed Searsport LPG tank. People who have stopped by over the years to perform, be interviewed, or just to visit include singers Arlo Guthrie and Tom Paxton; reporter Helen Thomas; writer Bill McKibben; and even former Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger. Public affairs programs have ranged from the airing the Camden Conference to Boat Talk, to World Ocean Radio, Awanadjo Almanack (with Maine Boats, Homes & Harbors magazine’s own Rob McCall), and plenty more.

As the 9 o’clock hour approaches, Watters readies the studio for the hand-over to Jon E. Ford as the station changes gears for his show “Scouting the Perimeters.” Wide-awake now, WERU is buzzing. The regular staff has arrived. Radio production is under way in the second studio, and other volunteers are preparing their shows, maintaining the music library, and helping in the office.

Watters packs up and heads out the door. As she leaves, she says, “You know, we are really lucky to have this great community asset!”

During the rest of the day, the format will change every few hours from spoken word to rock and free form, then to news, then perhaps from jazz to blues to soul. The singer Emmylou Harris once said about WERU: “You never know what you’re going to hear, and that’s what radio is all about.”

Greg Rössel lives in Troy and wears the hats of boatbuilder, instructor at the Wooden Boat School, president of the WERU board of directors, and host of “A World Of Music” radio show.