David R. Getchell, Sr., conceived and developed MITA’s original concept: trade member access to certain Maine islands in return for monitoring and care for the sites. “I’ve been accused of being a do-gooder. My reply is that someone should be.”

David R. Getchell, Sr., conceived and developed MITA’s original concept: trade member access to certain Maine islands in return for monitoring and care for the sites. “I’ve been accused of being a do-gooder. My reply is that someone should be.”

Photographs by Robert L. Drake Doug Welch (left, with David Getchell, Sr.), has been Executive Director of the Maine Island Trail Association since 2007. The organization’s top choice for the work of monitoring the islands are these seventeen-foot, aluminum, outboard-powered Lunds.

Doug Welch (left, with David Getchell, Sr.), has been Executive Director of the Maine Island Trail Association since 2007. The organization’s top choice for the work of monitoring the islands are these seventeen-foot, aluminum, outboard-powered Lunds.

Many of Maine’s coastal islands have been open to public access over the years, yet as recently as 1987 many of the smaller, more remote ones had been almost forgotten, while others closer in had become all-too-popular, littered and damaged by careless visitors. It was then that avid outdoorsman and former editor of the National Fisherman, David R. Getchell, Sr., wrote in the Island Institute’s 1987 Island Journal of a vision for the establishment of “a salty waterway [from Casco Bay to Jonesport] that winds through historic country, packs excitement and challenge for novice and expert alike, provides its followers with magnificent vistas and is of a length that assures a formidable test for those attempting it from end to end.”

Getchell, who is a native Mainer, envisioned a trail for “serious, self-sufficient small [outboard] boaters [like himself], those who understand and are capable of meeting the challenges of small boat cruising in the ocean.... End-to-ending a Maine Island Trail would not be for novices because of the simple fact that the sea allows fewer mistakes in judgment than...when solid ground is underfoot.”

The following year, Getchell, joined by 30 others of like mind, founded the Maine Island Trail Association to encourage stewardship and low-impact use of coastal islands by small boaters for picnicking and camping. Using his small, aluminum outboard boat, Getchell surveyed the Maine coast from Kittery to Eastport. He selected 42 of the 1,300 islands owned by the state to become the core of what would become the 300-mile-long Maine Island Trail. Within a year, three landowners had added their private islands to the trail, allowing MITA members to use them for day trips or camping. In return, association members agreed to monitor and help care for the islands.

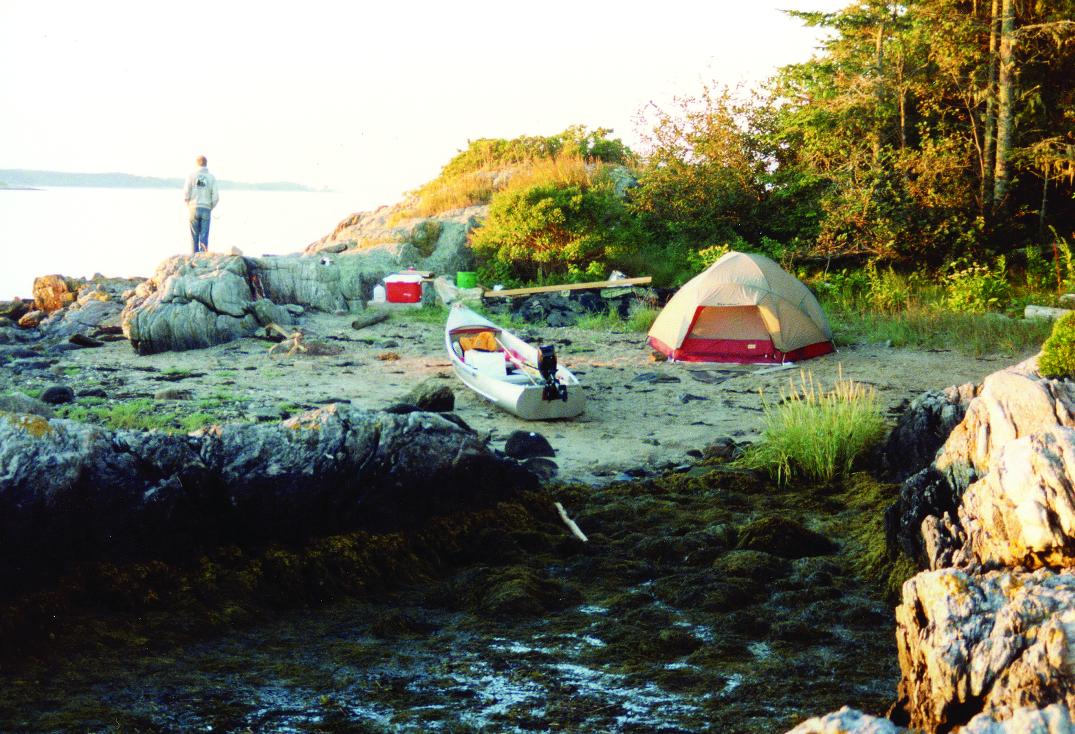

MITA members are rewarded with views like this while visiting islands on the Maine Island Trail. In return for the privilege of access, members pay annual dues, agree to abide by all island-owner guidelines, and help monitor and care for the islands.

MITA members are rewarded with views like this while visiting islands on the Maine Island Trail. In return for the privilege of access, members pay annual dues, agree to abide by all island-owner guidelines, and help monitor and care for the islands.

“All of a sudden [the concept] looked like it would work,” said Getchell, who even now at age 83 remains active in MITA, which celebrates its 25th anniversary in 2013. “I’ve been accused of being a do-gooder. My reply is that someone should be.”

MITA was spun off from its parent, the Island Institute, in 1992 to become a separate organization. MITA now has some 3,700 annual members—paddlers, sailors, powerboaters, and landlubbers—who monitor and maintain 200 coastal sites, mostly on islands. The trail now extends 375 miles from New Hampshire to Machias Bay. It becomes progressively more ruggedly remote as it threads its way down east past coastal islands, along protected saltwater rivers, and around exposed capes. In 2000, private sites on the trail surpassed public ones; by 2007, more of the private owners were corporations and non-profit organizations than were individuals. Regardless, on all sites, MITA trades recreational management and stewardship services for membership access.

“MITA has grown seven times bigger,” said Doug Welch, 46, who has been executive director since 2007, and who oversees a staff of seven from MITA’s Portland office. “It has evolved to become a little less grass roots and a little more institutional. Our mission statement—To establish a model of thoughtful use and volunteer stewardship for the Maine islands that will assure their conservation in a natural state while providing an exceptional recreational asset that is maintained and cared for by the people who use it—hasn’t changed. We still march under that banner.”

“MITA sites are bare-bones, camp-on-the-beach,” added Welch. “Most current visitors are day-trippers, three-quarters of them in kayaks.”

MITA members receive an annually updated guide with sites charted, guidelines noted, and landing places, hiking trails, day-use, and camping spots designated. It also includes tide and weather information, and essays on such topics as Leave No Trace principles, coastal ecology, wildlife, and archaeology. Thirty trained volunteer Monitor Skippers use MITA’s fleet of Lund outboard skiffs, and 120 trained Adopt-an-Island Stewards use their own boats to check each site, usually weekly. They pick up trash, record usage and environmental conditions, and talk with visitors.

Early on, the Maine Island Trail appealed more to small boat campers. These days, most visitors are day-users, although sites along the trail are open to MITA members who practice Leave No Trace visitation and camping principles.

Early on, the Maine Island Trail appealed more to small boat campers. These days, most visitors are day-users, although sites along the trail are open to MITA members who practice Leave No Trace visitation and camping principles.

“Our members have no authority to enforce any guidelines or laws, only to help people understand Leave No Trace use and encourage them to do the right thing,” said Welch. On last year’s annual cleanup, 135 volunteers found the campsites and trails on 48 islands to be almost litter-free. They found plenty of detritus on the shore, and removed 205 bags of trash, 65 large items (tires, plastic totes, foam blocks, etc.), and about 80 lobster buoys that they returned to local fishermen. (They also found a bottle with a message inside from a three-year-old girl in New Brunswick, Canada.)

Through outreach efforts and partnerships with conservation-minded organizations, non-profits, and state agencies, MITA continues to encourage responsible usage, address island challenges, and manage the trail’s public islands. MITA is financed by dues, contributions, a Donate-a-Boat campaign, partnerships with corporations such as L.L. Bean, and the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands.

Today, the Maine Island Trail, America’s first water trail, is a model of sustainable recreation and has inspired others to establish some 500 similar trails from Florida to Washington State. Getchell himself co-founded the North American Water Trails Association. He has also founded the Georges River (Maine) Land Trust Conservation Trails Program and has written books on water trails and motor boat cruising.

“My heart’s always been with the Maine Island Trail,” said Getchell. “It’s very rewarding to see water trails developed nationwide in our wake. But best is knowing that Maine’s wild islands will be cared for.”

“MITA’s biggest challenge is combating the [public’s] growing disinterest in outdoor recreation,” Welch said. In the extreme, he fears, lack of interest could result in poor future choices when it comes to coastal and island uses.

“We need a constituency who are stewards of the wild islands and will fight for them politically,” Welch said. “So we work very hard to get young families involved. The only way people will care for these places is to visit and understand how to make their visits low-impact, to see how just picking up trash makes one of Maine’s precious islands more perfect.”

Mary and Bob Drake live on a Maine island themselves (in season), and visit other islands as often as possible in their 15-foot Grumman Sportboat.

For more information:

Maine Island Trail Association

58 Fore St., Suite 30-3, Portland, ME 04101

207-761-8225; www.mita.org